Books

In Praise of Sylvia Plath's Forgotten (Sorority) Sister

A tragic early death can do wonders for a writer’s reputation. On October 27, Google dedicated its search page to the late Sylvia Plath, who would have turned 87 that day, had she not taken her own life, at the age of 30, back in 1963. It seems unlikely that Google will ever dedicate its daily doodle to the life and work of, say Edward Field, a gifted poet of Plath’s generation who is still alive at the age of 95. Nor is the internet likely to ever light up with praise for the likes of Maxine Kumin, A.R. Ammons, David Bromige, Robert Bly, Lucille Clifton, or any number of other poets who lived too long to die tragically young. Denise Levertov, another excellent poet of roughly the same generation as Plath, is never likely to get the same attention. At the end of her life, she traveled to various conferences and lectured on the art of poetry and spirituality, while she was suffering from lymphoma and, eventually, pneumonia and acute laryngitis. A tragic early death is generally regarded as more romantic than a courageous late one.

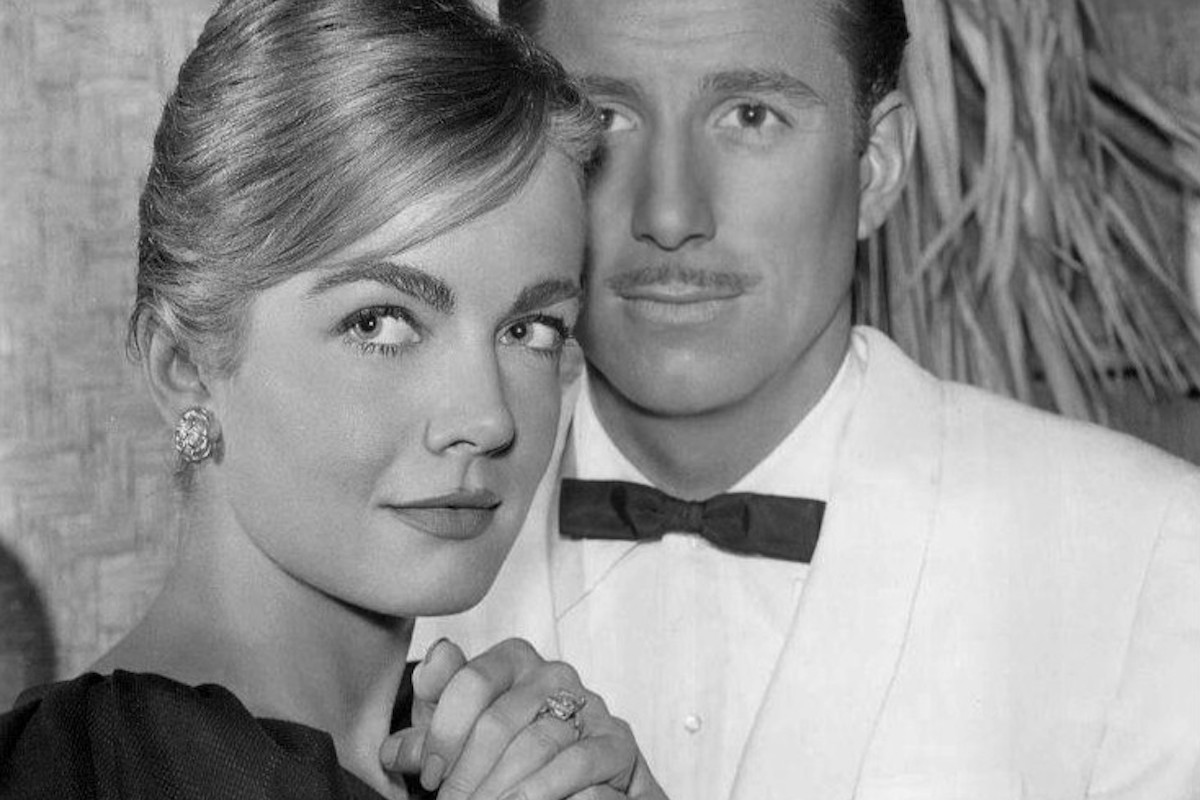

Joanna Barnes in 1959 (wikicommons)

Another writer never likely to get the praise she deserves is Joanna Barnes. Like Plath, Barnes was born (in 1934) in Boston, MA. Like Plath, Barnes attended Smith College (she was a year behind Plath). Like Plath, Barnes majored in English and was a member of the Phi Beta Kappa sorority. And, according to Wikipedia, “Barnes received the college’s award for poetry, the immediate successor to Sylvia Plath for this recognition.” Both women were also attractive and blonde. The similarities pretty much end there, however. Barnes initially pursued an acting career and found plenty of success. Before the ink was dry on her diploma from Smith she landed her first television acting job, on a TV series called Tales of the 77th Bengal Lancers.

Her first big film role came in 1958, when she landed a supporting part in Auntie Mame, starring Rosalind Russell. She played Jane in the 1959 MGM film Tarzan, The Ape Man. And the following year she appeared in Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus. Her most memorable film role, as least as far as Baby Boomers are concerned, was probably in the original version of The Parent Trap, in which she played Vicki Robinson, the woman who (temporarily) comes between Brian Keith and Maureen O’Hara. (She would later play the smaller role of Vicki Blake in Nancy Meyer’s 1998 remake of The Parent Trap, which starred Lindsey Lohan.) For most of her Hollywood career, however, Barnes did supporting work in a number of iconic TV series of the Baby Boom era: Maverick, Have Gun Will Travel, The Beverly Hillbillies, 77 Sunset Strip, Dr. Kildare, Mannix, Hawaii 5-0, Charlie’s Angels—the list goes on and on (only two TV series in history have contained the number 77 in their titles and Barnes guest-starred in both of them; make of that what you will).

In the late 1960s, Barnes returned to her first love—writing. Her first book was a quickly forgotten decorating guide called Starting from Scratch. In 1970, Arbor House published her first novel, The Deceivers. It seems clear that the book was modeled, at least in part, on Jacqueline Susann’s 1966 monster bestseller Valley of the Dolls. Both books follow a group of show-business professionals of varying degrees of talent as they experience the highs and lows of fame and fortune, and both books contain plenty of explicit sex. As if to emphasize the kinship of the two books, paperback editions of The Deceivers carried a blurb from Susann proclaiming the book to be “a big, stylish, impossible-to-put-down novel.”

But The Deceivers, without actually being a great novel, is a far better book than Valley of the Dolls. Both Jacqueline Susann and Joanna Barnes had plenty of experience in show business before turning to writing novels. Susann’s experience was mostly in live theater but she also did television work. Curiously, both women guest-starred in episodes of Mannix. Both Valley of the Dolls and The Deceivers depict the ways that women tend to be treated as sex objects by powerful men in the entertainment business. But The Deceivers leans into this theme.

The most sympathetic character in Barnes’s novel is probably Laura Curtis, an orphan (sorta, her father is unknown and her mother has abandoned her) raised by financially strapped grandparents. When a talent scout discovers Laura’s beauty and gift for recitation at a high-school speaking competition, she offers to take Laura to New York and help her find work in showbiz. The grandparents, ailing and cash strapped, have little choice but to accept the offer.

Soon Laura, at the age of thirteen, is co-starring in a film with Harris Bolding, a man of about 60 and described as England’s greatest Shakespearean actor. As the production nears its conclusion, Laura and Bolding are asked to pose for a few publicity photos by a still photographer. Here’s how Barnes describes what happens next:

“I’m going to miss you, pussycat,” Harris whispered, his mouth tickling her ear.

“Okay, let’s have a nice smile from both of you.”

The camera kept clicking. Harris’s fingers straightened the belt in back of her skirt and smoothed it. His hand patted her backside lightly.

“Hold it. Don’t move, please. This is very close.”

Harris was stroking her. She tried not to move.

“Reloading,” said the still man, turning to get a new roll of film from his case.

Harris whispered close in her ear, something she didn’t hear clearly. His hand left her, and when she felt it again, it was against her bare skin. He had somehow undone the zipper of her skirt and slid his hand inside her panties at the waist. He was cupping her buttocks, squeezing gently with his fingers. Laura didn’t know what to do. The photographer was threading his camera. He wasn’t looking at them. Laura felt the warm hand kneading her flesh. The still man was fixing his focus, peering through his camera. He said nothing, just looked at them.

“Makeup!” he finally called, not taking his eyes off them.

“Here I am,” Maury said. The man murmured something to him and he went away.

Laura felt Harris withdraw his hand slowly, his fingers lingering over her.

“Laura, they want you in the production office.” It was Fred. “Come with me.”

She followed him, not daring to look back.

“Skip the production office,” he said, as soon as they were out of hearing. “Go to your dressing room until we’re ready for you. And let’s not mention this to anyone. I mean anyone. It wouldn’t be good for you, and it wouldn’t be good for the show. Understood?”

She nodded.

“The back of your skirt is undone. Zip it.”

This is far from the only time in the book that an older more powerful man in show-business abuses a much younger female protégé. The book preceded the #MeToo movement by nearly fifty years, but feels as if it might have been inspired by the reporting of Ronan Farrow, Jodi Kantor, or Megan Twohey.

Unlike Jacqueline Susann, who never surpassed Valley of the Dolls, Joanna Barnes continued to grow and improve as a writer. She became a regular book reviewer for the Los Angeles Times and wrote a syndicated newspaper column called “Touching Home.” Her second novel, Who Is Carla Hart? (1973), was compared favorably to Joan Didion’s Play It As It Lays by Kirkus Reviews. But it was her third novel that really delivered on all her early promise. Pastora, published in 1980, is a 750-page historical epic that can be fairly described as California’s Gone With the Wind. It does for California’s most famous historical epoch (the Gold Rush) what Margaret Mitchell’s novel did for the American South’s most famous historical epoch (the Civil War).

Like GWTW, the story is told largely through the eyes of its female protagonist. The plot follows the fortunes of Lucy Curtis, an impoverished young orphan from Missouri who, desperate to escape her life as a hotel maid, rashly marries a silver-tongued Irishman who proposes to take her west and seek wealth by raising sheep in northern California’s gold country. Unfortunately for Lucy, Caleb Bates is a polygamous conman who rapes her on their wedding night and then continues to abuse her all the way to California. Later on, he is killed by Indians (or so it appears) but Lucy nonetheless pursues his dream and establishes herself as a successful shepherdess, or “Pastora,” as her Spanish-speaking neighbors refer to her.

Barnes deftly weaves Lucy’s story with some of the most fascinating (and sometimes infuriating) episodes of California’s early days as a state. She is particularly good at resurrecting largely forgotten females who figured prominently in that history, such as young Helen Crosby, who carried California’s original statehood papers across the Isthmus of Panama, and on to San Francisco, secreted in her silk umbrella; and Mary Ellen “Mammy” Pleasant, an African-American woman who, in 1866, successfully sued a San Francisco streetcar company that refused to carry black women (this and other successful lawsuits earned her the name of “the Mother of Human Rights in California”). She also writes about how the Wiyot Indians of Humboldt County were massacred by white settlers there. Her novel is filled with sympathy for history’s victims and underdogs: women, minorities, the poor, even the beasts of burden.

Alas, Pastora never received the attention it deserved. When Barnes was writing about showbiz, she received at least a smattering of approval from book reviewers. But when she turned to historical fiction, serious critics ignored her. Which is a shame. Barnes is a direct descendent of Frederick Low, the ninth governor of California. She studied western US history at UCLA and she worked on her novel in close consultation with John Caughey, one of the most honored California historians of his generation. The book was published in an era when massive historical romances—Shogun, The Thorn Birds, Trinity, Chesapeake, Lonesome Dove—were thick on the ground, which may account for it being overlooked. It probably also didn’t help that Barnes’s most recent film role had been as the female lead in I Wonder Who’s Killing Her Now, one of the worst films of the 1970s, if not in the entire history of film.

Sylvia Plath was a great poet and she deserves to be celebrated. But we shouldn’t allow the sentimentality that often attaches to promising artists who die young—Plath, James Dean, Janis Joplin, David Foster Wallace—to blind us to the many excellent artists who not only showed brilliant early promise, but who also went on to fulfill it. Next month, god willing, Joanna Barnes will turn 85. Google won’t celebrate it. But, if you are fan of American popular fiction, you ought to do so by finding a copy of her long-out-of-print novel Pastora. It may not be as famous as The Bell Jar, but it’s a hell of a lot more fun.