Communism

A Letter From Hong Kong

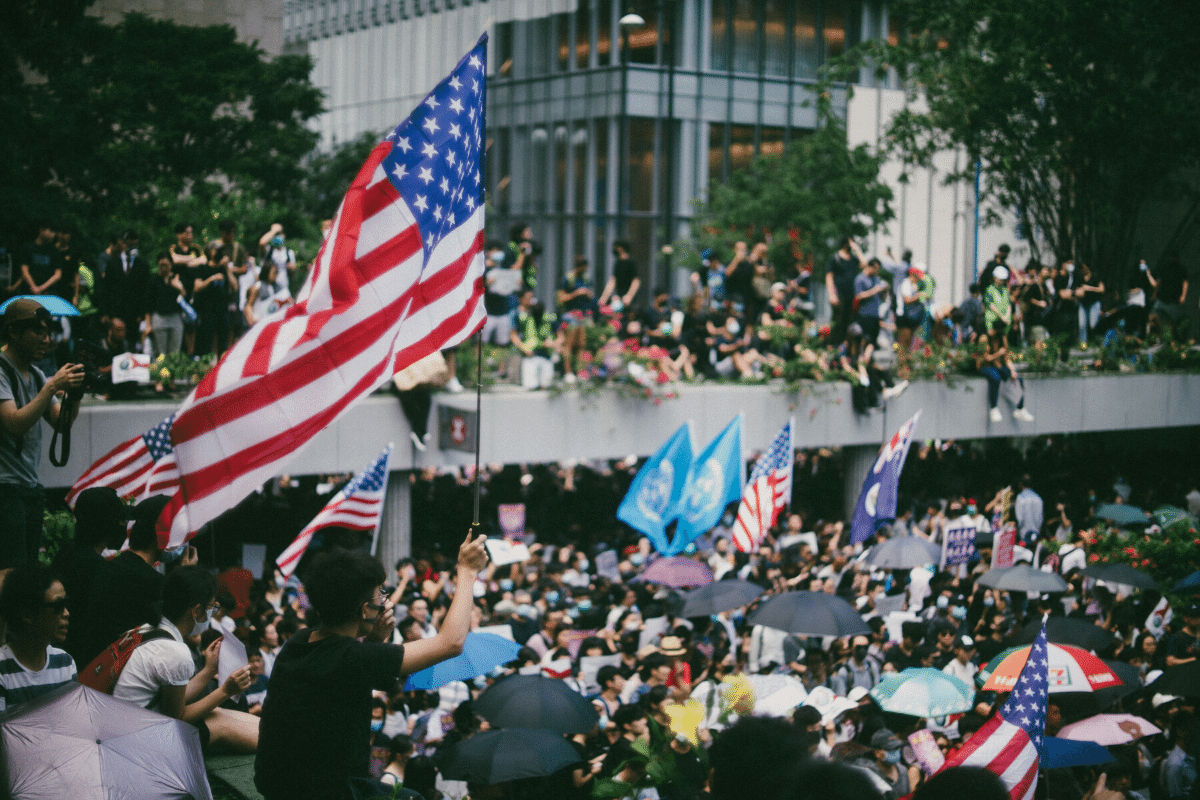

The myths of the obedient Hong Kong child, of the disciplined dronelike worker, of the person who puts money above everything else, are shattered for ever.

The normal coexists with the brutal. Last Saturday, in Hong Kong, carefree expat children walk by my apartment building, holding party balloons as Puma police helicopters buzz overhead. Less than a mile away people are fired on with tear gas and water cannon spewing blue dye. I imagine that this is what it felt like in the last days of the Shah.

My days are not usually surreal. I am a teacher at Lingnan University, a liberal arts college and the smallest of eight public universities in Hong Kong. I have lived and worked in Hong Kong for twenty years; my wife and I raised our two children here. We are foreigners, but with a deep attachment to this city and its people. The causes of the current turmoil will take years of research to understand properly. Historians will find these causes in the Chinese family, in the class structure, in demography, in generational change, in new forms of communication, in political society and in several other factors still opaque to us. But where are we in Hong Kong now? And what is the situation of the students I teach? A personal snapshot must suffice.

I want to say that this feels like a pre-revolutionary situation, except that there is no state to topple and no alternative to it. Rather there is a local government—Carrie Lam’s administration—that has stopped governing and that is now little more than a reed of Beijing. In that sense, the Communist Party has already taken over Hong Kong and is watching it descend into chaos. Perhaps the logic is that the worse it gets here, the greater the rationale is for stepping in and ‘saving’ Hong Kong from itself.

Or Beijing may demand that Carrie Lam ramp up the repression, invoking emergency measures to enable untrammelled censorship, search of residence, seizure of property, deportation, arrest, indefinite detention, and so forth. Emergency Powers were last employed here in 1967 when the British colonial government cracked-down on the ‘Leftist riots,’ a movement with some local support but basically an off-shoot of the Cultural Revolution. However, a colonial government was accountable to the British parliament and could be relied on, in time, to restore the status quo ante. This time, there would be no restoration. The ‘One Nation, Two Systems’ regime crafted for Hong Kong by Mao’s successor Deng Xiaoping would be dead. It may well be dead already.

Much looks different. The myths of the obedient Hong Kong child, of the disciplined dronelike worker, of the person who puts money above everything else, are shattered for ever. But can Hong Kong people triumph over the Communist Party? Surely not and they know it. What, then, is the point of their fighting on? Dignity and self-respect. Bystanders are responsible for what they don’t do—in this case push back on a growing tyranny. Years from now, historians will recall that at a time when the West had descended into identity solipsism, there was a place on earth where people cared more for liberty and their city than their lives. They will marvel at what an unsated people can and will do.

Today, the most visible aspect of repression in Hong Kong is the police. Its members feel abandoned by their government and by large sections of Hong Kong people. Increasingly isolated from their neighbours, their children insulted and bullied at school, harangued by residents when they enter districts—Sha Tin, Mong Kok, Tin Shui Wai, Tung Chung—in pursuit of protesters, the police are turning inwards and developing a siege mentality. In the wings, they are cheered on by the mainland Communists as true defenders of the motherland.

Against them stand the shock-troops of the protest movement—the ones doing the front-line fighting. They are young men and some women chiefly from the working classes of Hong Kong, youth with nothing material to lose, angry and embittered. Their philosophy is: freedom, respect and opportunity for all, or together we burn. Behind this phalanx, literally and figuratively, are more middle-class youth. One tells me that she feels guilty to let her working-class comrades take the brunt of police violence; and more of her friends are now taking part in the melee. Several have been tear-gassed. They are in no mood to compromise. She adds: “Soon, people will die. And if you ask me: ‘Would you die for Hong Kong?’ I say to you ‘yes.’” She is 21.

Term begins with a two-week student boycott. Students have told me that the word ‘boycott’ is misleading; it will be more like disruption, with students occupying lecture theatres and administrative buildings. The student demands (there are five of them) will not be granted by the government; and one can anticipate a growing frustration and radicalization on campus. I am guessing that the epicenter of the protest movement will shift from the streets to the universities. And here lies a big danger—for the students.

As Hong Kong approximates ever more closely a police state, the university campus will be one of the few sites left for safe student protest. Outside of it, several of its leaders are being rounded up. It is not unheard of for police to enter the university gates, but that may be one of the last remaining taboos to be generally observed. For now. But if the students, frustrated by an intransigent government, radicalize further, they may destroy the base of their protest. Social movements have their own élan. They are not governed by the norm of maximum utility. They do not seek advice from others or take much notice when it is given. But if this one did, I would plead: do not para-militarize the campus. Do not wear your black shirts or don your goggles and your masks in the classroom. The professors and the staff are not your enemies. They cannot harm you and some of them will willingly help you come what may.

It is not for the professor to take a political stand in class, to use the lecture theatre as a platform for propaganda. All students must feel welcome and assured that they will be treated fairly, whatever their views. Hong Kong students do not all think the same about the current protest. Mainland students also study at my university and some, perhaps the majority of them, oppose Hong Kong radicalism. But impartiality in the classroom does not require neutrality beyond it. The obvious can and should be said aloud. What is that?

Hong Kong students are right when they refuse to conflate ‘China,’ a great civilization, with the Communist Party, a brutal organization. They are right that the Communist Party threatens every political and civil value they cherish: free expression, free movement, free association, free voting, freedom of religion. The Party’s priority is total control. Its central demand is total loyalty. It has no love for the students. It will show them no mercy. And, essentially, the students are alone, save for the support of their own families, friends and communities. If the People’s Armed Police flood across the Shenzhen border, or if the PLA is unleashed from its garrison at Admiralty (the eastern part of the business district), the world will watch and condemn. Prime Ministers and Presidents will look severe and utter the usual platitudes of rebuke. But in time the West will make allowances and, in truth, there is little it can do. Macroeconomics will cauterize disapproval.

Nor, sadly, can Hong Kong youth expect solidarity from the most militant of Western university students and faculty. They lost their taste for freedom years ago. Israel is apparently a bigger offense to their sensibilities than Communist China (or Iran). In all significant respects, these Westerners are the opposite of the young people I know. While Hong Kong students detest Communism, many of their Western counterparts embrace Marxism. While Western post-colonialists deride Western civilization, Hong Kongers wish they could have more of it. When Hong Kong students talk of a safe-space they mean a shelter from tear-gas and rubber bullets, not a refuge from offensive words. A trigger warning is not a professor’s presage of a painting by Goya; it is the sound of a revolver shot discharged skywards in the Causeway Bay night.

In Under Western Eyes, Joseph Conrad describes pre-revolutionary Russia as ‘an oppressed society where the noblest aspirations of humanity, the desire of freedom, an ardent patriotism, the love of justice, the sense of pity, and even the fidelity of simple minds are prostituted to the lusts of hate and fear, the inseparable companions of an uneasy despotism.’ Today, these noble aspirations have moved eastwards. All rebellion produces hate and fear. It is an open question whether love of this city, a belief in justice and a sense of pity can prevail over baser passions.