Activism

In Defense of Political Hypocrisy

Everyone with political beliefs benefits from systems that they oppose in some way.

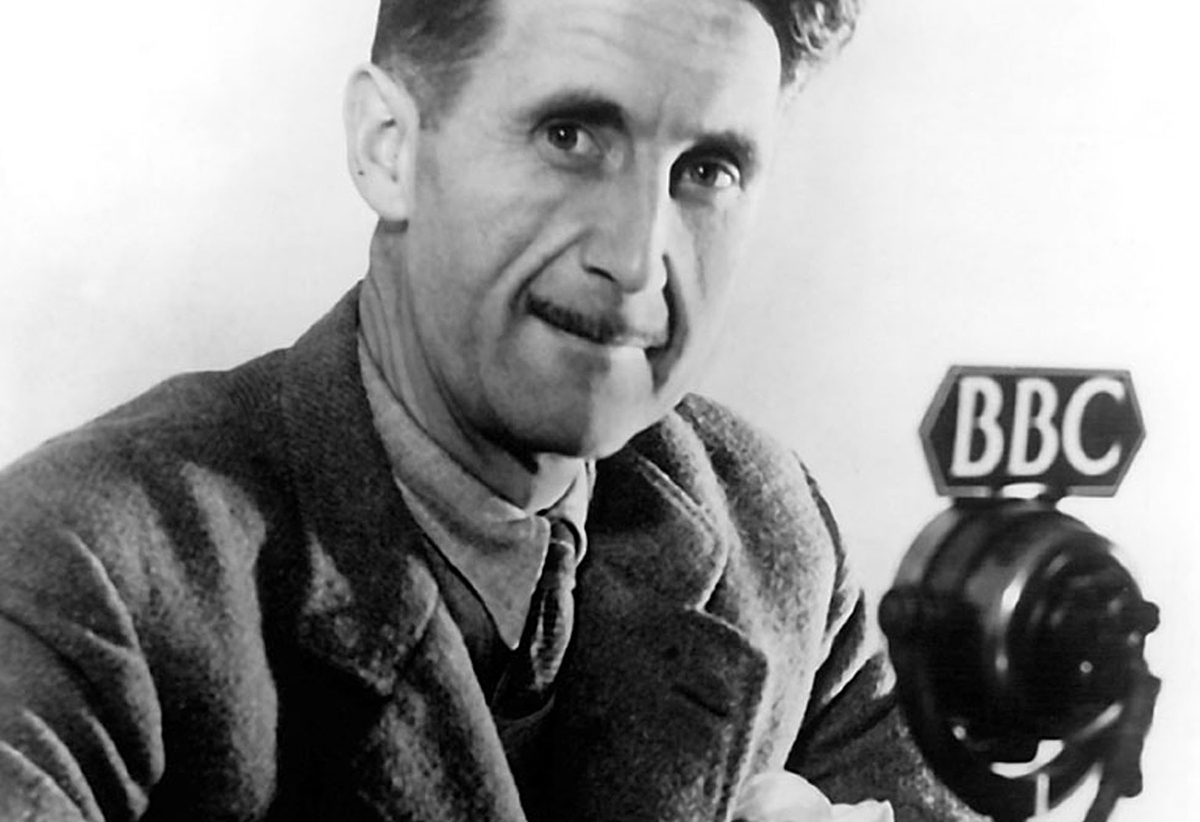

Bernie Sanders’ campaign has come under fire for not paying staffers the $15 minimum wage he promotes—and for using the private health-care system he often criticizes as immoral. Similar scorn is being hurled at environmentalist-minded celebrities who recently traveled to a Google climate-change conference via private jets, and even yachts. I am far from being ideologically aligned with Sanders or most Hollywood stars. But I will use the occasion to make a broader point about those who insist we all practice what we preach politically. Simply put: It’s petty to weaponize the spectacle of political hypocrisy to score points and avoid taking the other side seriously. As George Orwell put it in his essay about Rudyard Kipling, “a humanitarian is always a hypocrite”—since his or her standard of living is dependent on practices that he or she deems criminal. But that doesn’t mean we can simply ignore their arguments.

The first and most obvious problem with targeting a political opponent’s hypocrisy is that the practice always is applied selectively. Libertarians—and I’m including myself—sometimes scoff casually at the upper-class socialist who condemns capitalism while benefiting from the many innovations and luxuries that capitalism made possible. But those same libertarians often will fail to acknowledge that they benefit from public education, subsidies and infrastructure whose scope (or even, in some cases, very existence) they oppose. In his 2016 bestseller Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis, J.D. Vance pointed out a species of this phenomenon he observed in poor Appalachian communities, where strident conservatives preached against the vices of government reliance while collecting welfare benefits and remaining perpetually unemployed.

If this kind of hypocrisy can be taken as a fatal flaw in regard to any argument, then surely all have sinned and none can judge. Everyone with political beliefs benefits from systems that they oppose in some way. But just because a libertarian or conservative benefits from public programs doesn’t give critics license to dismiss their ideas about why those programs may be inefficient, ineffective or unjust. By the same token, just because Bernie Sanders is a millionaire who flies first class and does his fundraising using software developed by Silicon Valley billionaires doesn’t mean his criticisms of market failures and social injustice aren’t worth considering.

Moreover, the demand that activists practice what they preach in all cases serves to impose a special moral burden on those who rouse themselves to the improvement of society. In some limited cases, such as with philosophers who presume to describe universal truths, this burden is legitimately imposed. (Voltaire, for instance, threw out his principles and advocated for censorship when Rousseau publicly criticized him; and this fact deserves to be highlighted in the historical record.) But these rare exceptions aside, nobody has any special obligation to society by dint of their viewpoint. Not even a politician. A democratic socialist who thinks the government ought to raise taxes isn’t a hypocrite for limiting his or her tax remittances to the legal rate. Just as a libertarian isn’t morally required to take a private toll road to get from point A to point B instead of a public highway. The classical liberal economist Friedrich Hayek benefited from Medicare, a government program he opposed in principle, when he came to the United States in the mid-’70s—and he wasn’t wrong to do so. And whatever you think of Leonardo DiCaprio’s climate message, he isn’t obligated to renounce his use of jets, limos and mansions.

One’s political ideology generally is a view of how all in society should behave—not just oneself. This often makes it literally impossible for someone to practice what they preach because they can’t control others. They have no choice but to live in and interact with society as it is, not as they wished it to be—and there’s nothing wrong with them doing so.

It’s not hard to think of modern instances of political hypocrisy that truly are morally outrageous—such as with a sex scandal involving a socially conservative Republican or ultra-woke Democrat. Nor is it out of bounds for the media to report on instances of apparent hypocrisy that reveal deception, hubris, ignorance or meanness—such as when a politician who publicly promotes the virtues of kindness and empathy is revealed to behave tyrannically among his or her staff. But these examples typically tend to involve the nature of a politician or public figure’s interpersonal relationships. Humans, being social creatures, always will judge such matters in a special way, as we view the way we treat those around us as a window into a person’s true character.

But in the modern political context, the definition of hypocrisy has greatly expanded to envelop a much broader group of reasonable people who are pursuing their own legitimate interests and advocating sincerely-held ideals within circumstances that they didn’t create. Raising the bar for what actually constitutes problematic hypocrisy would go a long way toward improving political discourse—because we’d spend less time skewering others for fictional moral lapses, and more time grappling with the actual issues that separate us.