Books

Against Literalism—'The Satanic Verses' Fatwa at 30

The intermingling of elements—culture, language, religion—is celebrated, while the concept of purity in identity and culture is repudiated as too constricting.

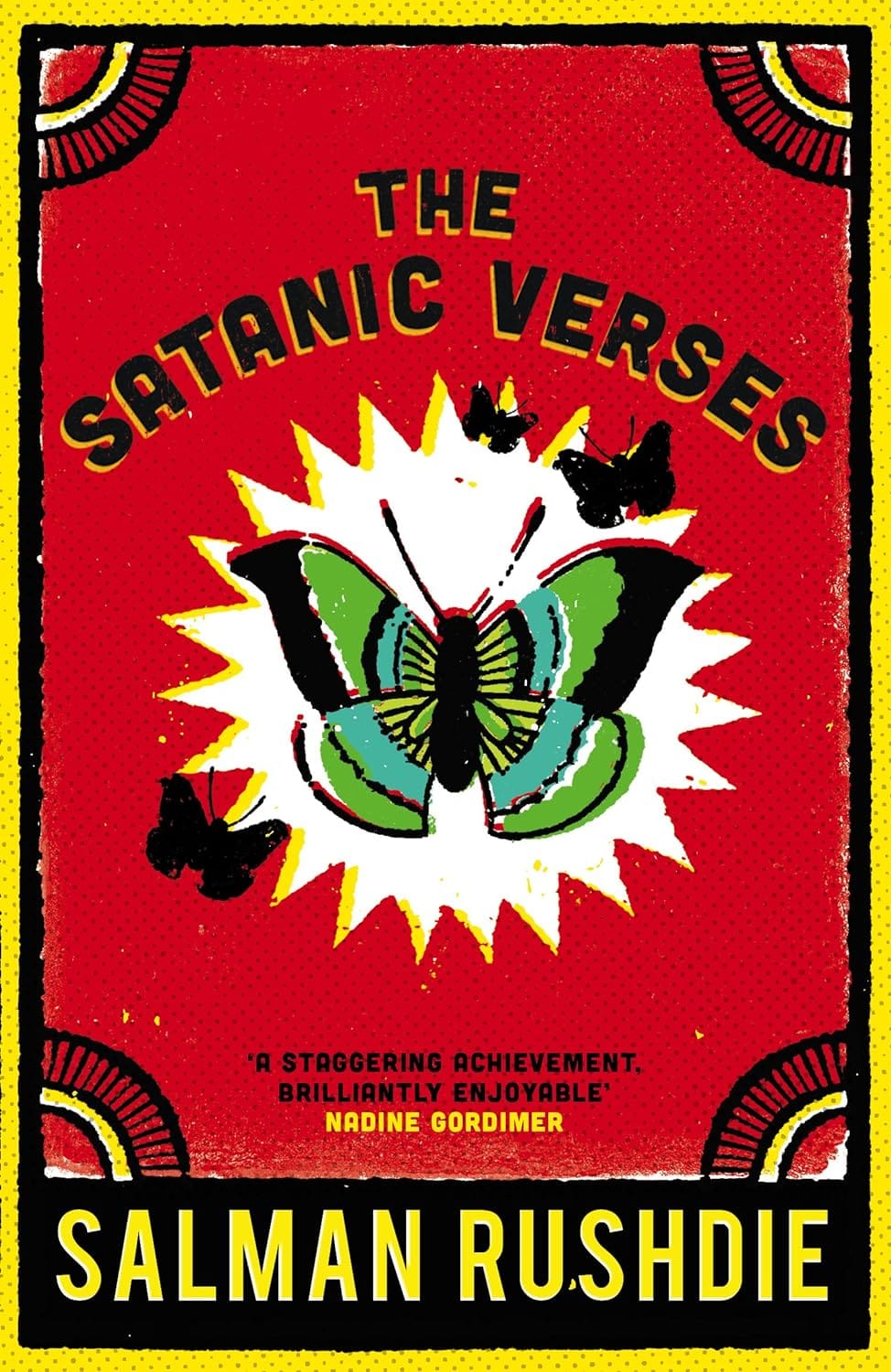

I have written elsewhere about the fatwa issued 30 years ago by a sinister religious cleric commanding the world’s Muslims to murder the writer and everyone involved in the publication of The Satanic Verses. But the best way to repudiate the authoritarian, constricted, literal mindset is by celebrating its opposite. And so, with as little mention as possible of the events the publication of The Satanic Verses engendered, what follows is simply an appreciative analysis of that extraordinarily epic, satirical, ironic, and multifaceted novel.

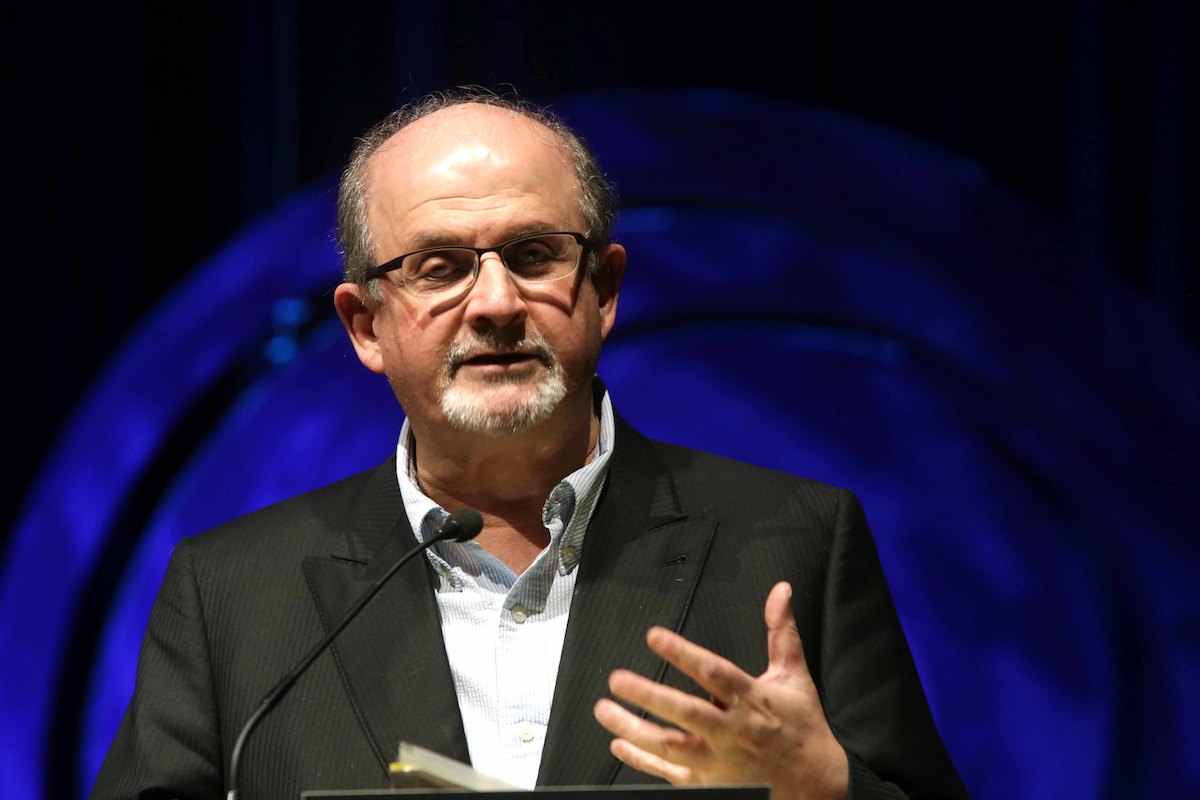

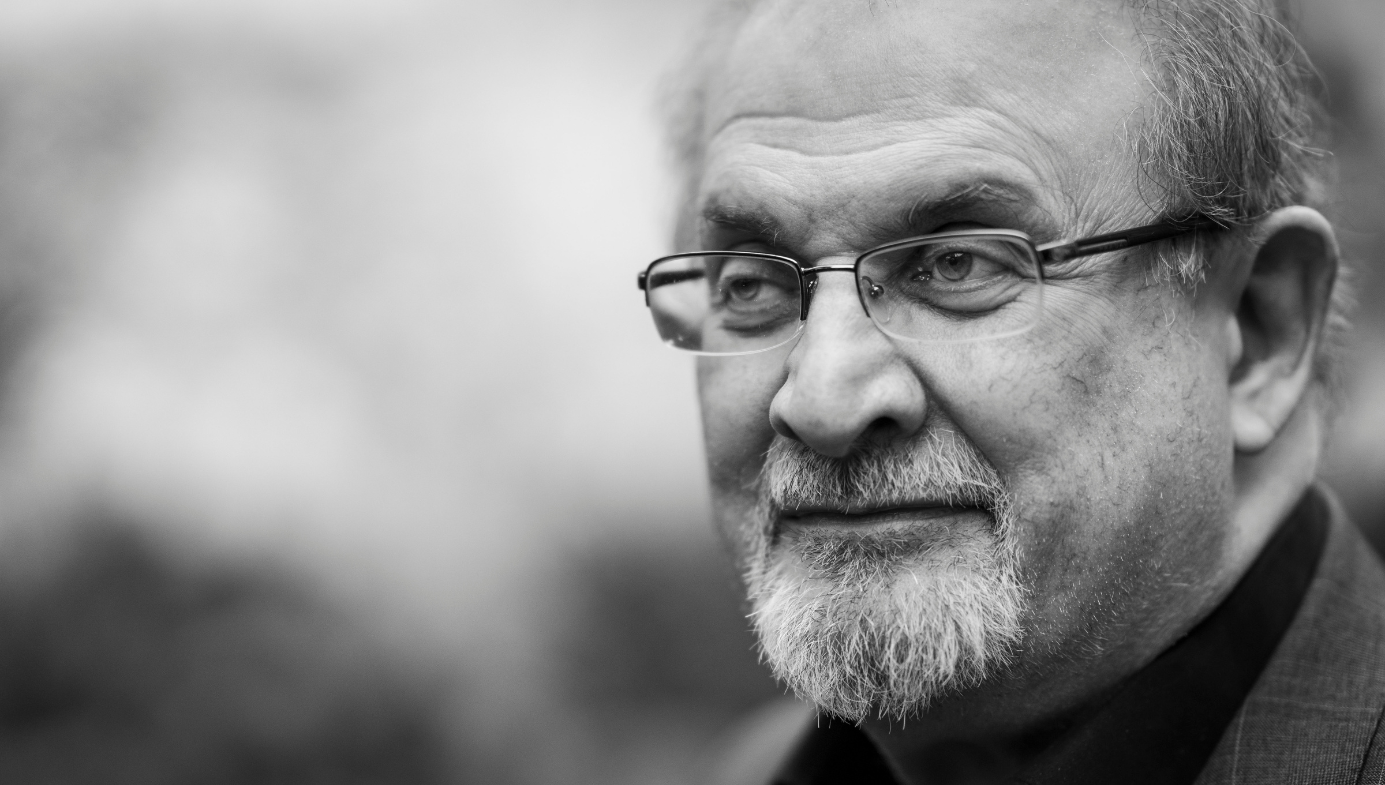

Salman Rushdie is one of the finest writers of recent times, whose work celebrates hybridity and intermingling of culture over narrow-minded puritanism.

This theme is at the heart of The Satanic Verses, as suggested by the questions posed near the beginning of the novel: “How does newness come into the world? Of what fusions, translations, conjoinings is it made?” These questions are asked as the two protagonists, Gibreel Farishta and Saladin Chamcha, fall from the sky above the English Channel after the hijacked plane they were travelling in is torn apart by explosives. Gibreel and Saladin are the only survivors but there is a price for this miracle. They both undergo a metamorphosis; Gibreel gains a halo while Saladin sprouts horns.

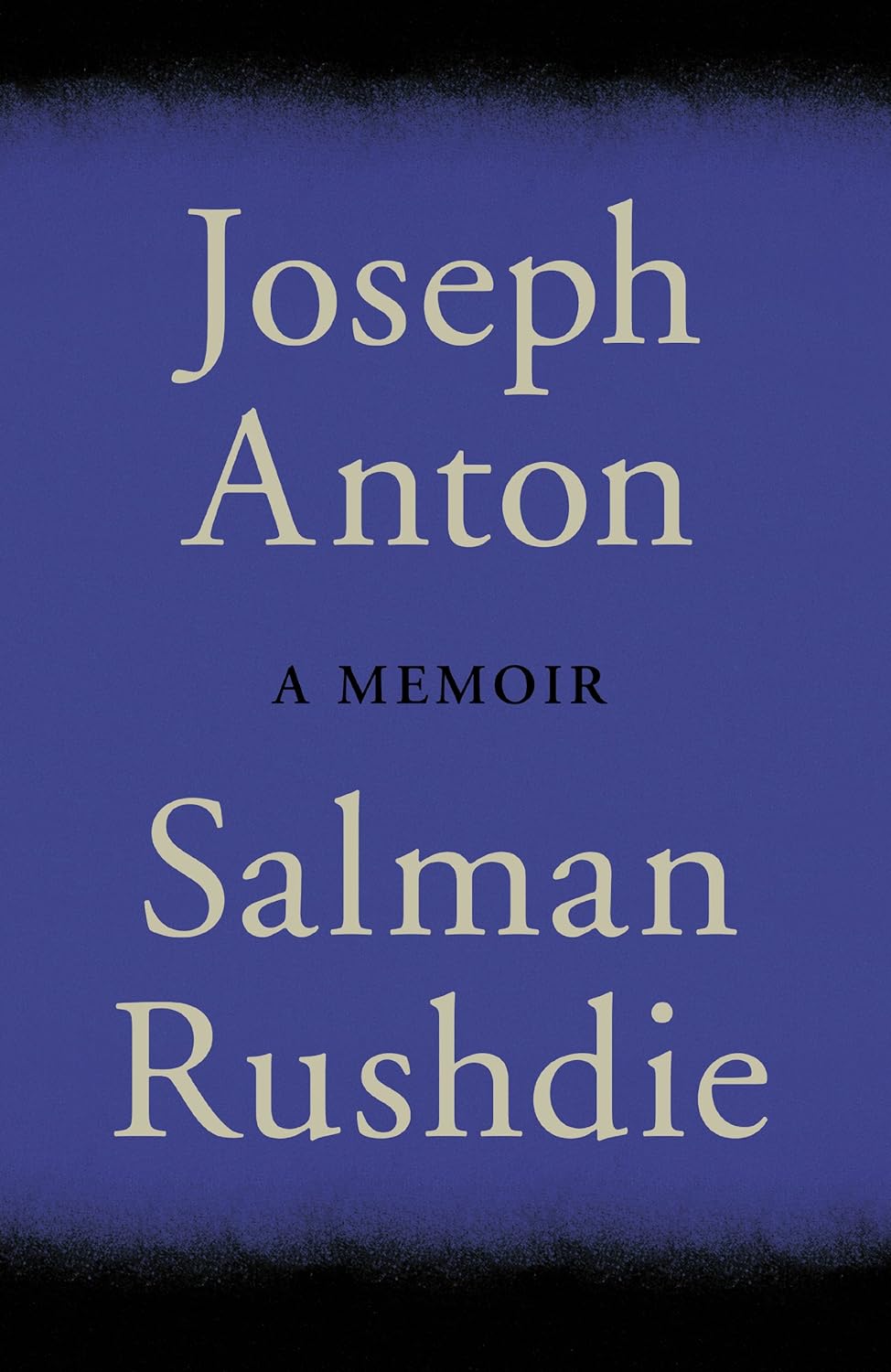

The story follows these two men as they grapple with these changes and explore themselves. In his memoir Joseph Anton, Rushdie states that his inspiration for the novel was the globalising world of modern times where migration and cultural rootlessness are norms rather than exceptions. The novel quotes Daniel Defoe on the plight of the devil, cast out of paradise and doomed to travel the world “without any certain abode.” This diabolic tragedy is treated by Rushdie with empathy as well as sympathy, for his own experiences inform the character of Saladin, whose transformation into a devil reflects his inauthenticity and rootlessness, his wearing of a mask to cover up the Indian heritage he is ashamed of and which he wishes to replace with an English identity. Rushdie says in his memoir that his sympathy is with the devil, as should be the case with all great poets, according to William Blake.

The novel’s protagonists are Indian-born Muslims. Saladin is a voiceover artist and an immigrant from Bombay to London whose shame about his Indian-ness and desire to be anglicised form the backdrop to a complex interrogation of what it means to be rootless and how migrants in a globalised world can find a sense of identity. Gibreel, meanwhile, is a legend of the Bombay movie scene whose recent health crisis has led him to lose his faith and travel to London to be with the woman he loves, Alleluia Cone. Famous for portraying Hindu gods on screen, Gibreel’s newfound archangelic nature sorely tests his mind—a newly godless man condemned to act as God’s (or is that Satan’s?) right hand on earth.

But both protagonists are hybrids who contain elements of the saintly and the diabolical. They both face challenges and crises of identity. Through them, Rushdie explores what it means to lose and then find one’s identity and what the true experience is of migrants whose rootlessness and existence in a foreign culture leads to a crisis of selfhood. The intermingling of elements—culture, language, religion—is celebrated, while the concept of purity in identity and culture is repudiated as too constricting.

Saladin reconciles with the father he thought he hated, accepts his Indian-ness, and begins to live authentically, while Gibreel’s end is much sadder. Rushdie celebrates the hybrid and the multifarious over the narrow-mindedness of those who wish to keep everyone in a straitjacket. Culture, civilisation, and identity mean, for Rushdie, open-mindedness and a rooted rootlessness; spiritual and intellectual strength arise from the hybrid while puritanism leads only to individual and collective suffering.

Rushdie himself has stated that these ideas are central to the book:

Those who oppose the novel most vociferously today are of the opinion that intermingling with a different culture will inevitably weaken and ruin their own … The Satanic Verses celebrates hybridity, impurity, intermingling, the transformation that comes of new and unexpected combinations of human beings, cultures, ideas, politics, movies, songs. It rejoices in mongrelization and fears the absolutism of the Pure … It is a love song to our mongrel selves.

The main narrative is interspersed with chapters devoted to parallel stories. Gibreel dreams of the prophet Mahound’s difficulties proselytizing for his new religion and his eventual triumph over those who laughed at him in Jahilia (Mecca?); he is drawn into the ambiguous recollections of a dying old woman whose past involves love and murder; a sinister imam, exiled in London, uses Gibreel’s power to revenge himself upon impurity and paganism; and Gibreel’s archangelic powers are used by a prophetess named Ayesha to convince an Indian village to go on a pilgrimage by foot to Mecca—and to part the Arabian Sea which stands in the way.

We are left to wonder if Gibreel was just insane, if the novel tells the sad story of a man’s mental decline. If so, did Saladin go mad, too? In which case, Gibreel, the archangel, was undone while the devil, Saladin, emerged triumphant and whole again to live authentically. When they fell from the sky the two men were physically and mentally intertwined, their bodies wrapped around each other. The hybrid nature of the two men is explored in great depth and with great beauty throughout the novel. Interconnection is explored with reference to contrasting concepts, such as love and hate, death and life, rebirth and reinvention, while Saladin’s experiences as an immigrant yearning to be accepted is an analysis of migration, change, and identity—and all the conflicts engendered thereby.

In the end, obsession with purity and rigidity give way to reconciliation and compromise; the colonial subject is freed from a mental oppression which says he is inferior; and hybridity is shown to be superior to purity, as epitomised by the sixteenth century Hamza-nama cloths which display, in the view of Saladin’s friend and lover Zeeny Vakil, “the eclectic, hybridized nature of the Indian artistic tradition…you could see the Persian miniature fusing with Kannada and Kerala painting styles, you could see Hindu and Muslim philosophy forming their characteristically late-Mughal synthesis.”

The Satanic Verses is critical of Islam, but not very. Mahound (Muhammad?) is presented as a secular leader who is slowly corrupted as his power grows (and whose supposed access to divinity is undermined by his companion, Salman the Persian, who notes the suspicious convenience of the archangel’s revelations to the prophet). But he is angelic in other ways—a freer of slaves and a man of principle willing to spare those who submit rather than just a warlord and temporizer. The book’s title relates to the historical episode in which Muhammad stated that some pagan goddesses could be brought into his new religion—an act which was quickly repudiated so as not to dilute the faith’s monotheism, and which Muhammad put down to being confounded by the devil masquerading as the archangel Gabriel.

In my reading, “the satanic verses” evoke human frailty rather than diabolical design. For Mahound they are a compromise, a way to ingratiate himself with the Jahilians and win new converts by accepting the existence of some lesser pagan goddesses; this is a secular, material tactic rather than an exercise in theology. For Gibreel, “the satanic verses” are the rhymes an embittered Saladin pours into his ears to turn him against Alleluia. Again: ambiguity, mixture, hybridity, and interconnectedness—good, evil, love, hate, death, life, compromise, and jealousy; all very human strengths and frailties.

“The satanic verses” is a phrase which also suggests hybridity because, as mentioned, they refer to Muhammad’s brief acceptance of pagan deities. The novel celebrates diversity and the multifaceted and so this mixing of paganism with Islam’s purity should be taken as the prime example of the beauty of hybridity. Why restrict oneself to narrow monotheism when there is so much colour and delight to be found in every tradition?

Ironically, life imitated art and Rushdie himself was transformed, like Saladin, into the devil; as he recounts in Joseph Anton (itself a remarkable and beautiful book and a cogent defence of freedom and literature), he was renamed “Satan Rushdy,” and his image was paraded by mobs to be scorned.

The greatest irony, though, is that a novel about the power of culture and literature and the superiority of expansiveness and mongrelisation to the narrow and the pure should itself become a focal point in the real-life battle between those things. As Christopher Hitchens put it at the time of the fatwa: “This is an all-out confrontation between the literal and the ironic mind.” This could describe the novel itself as well as the contest it aroused.

This is not a simple matter of West versus East (Rushdie would have much to say about such a simple demarcation), but a matter of civilisation versus barbarism, wherein the artists, secularists, writers, and reformers of all colours and creeds must make a united stand against the authoritarians and narrow-minded fundamentalists of all kinds and in all places, whether they be Islamists, righteous far-leftists for whom “dissent” means “impure,” windbag religious reactionaries, or white nationalists. On the latter group, recall Rushdie’s words, quoted above, on the strength and beauty of the hybrid compared to the weaknesses and fears of those who see change and mixing as a threat.

Baal the poet, an enemy of Mahound in the novel, sums up the writer’s task: “A poet’s work is to name the unnameable, to point at frauds, to take sides, start arguments, shape the world and stop it from going to sleep.” Once more, life imitates art—who better to epitomise this ideal than Rushdie himself? Who better than a great novelist with roots in multiple cultures to act as symbol of and warrior for freedom of expression, the power of literature, and the beauty of the multifaceted against the many enemies of those ideas?

Joseph Anton shows that Rushdie’s life and art are intimately jumbled up together—his was a family which encouraged rationalist criticism of the divine Qur’an and which venerated storytelling’s power to shape individuals and undermine tyrants. The family surname was changed to Rushdie by his father in honour of Ibn Rushd, known in the west as Averroes, that ironic and rationalist philosopher of the Islamic medieval golden age who opposed religious literalism and narrow-mindedness. This is a fact of which Rushdie is proud—in his memoir he reflects that at least he was on the right side of the right war armed with the right name for the task. If there were such a thing as destiny, it seems that Salman Rushdie would have been chosen as liberty’s champion. But there is only the material universe populated with imperfect beings and Rushdie is one of them—no saint, but a dogged and humane defender of civilisation.

I said I would try not to focus on the external events surrounding Rushdie’s novel but the content and themes of the book are, in the end, inseparable from what happened after the book was published. Hybridity, irony, and interconnectedness once more, it seems—the fictional and the real intermingling and synthesising to form a powerful defence of openness and civility.

The Satanic Verses is therefore not only a work of astonishing beauty but also a foundational document in the fight for culture, openness, civilisation, and civility against those who wish to see those things stifled by narrow-minded faith-based puritanism. Salman Rushdie’s life and work remind us of the importance of this battle and the necessity of remaining staunch and unyielding in the task of defending civilisation against its enemies in whatever grotesque permutations they appear.