recent

Dignity—A Review

If members of the back row lack dignity because of their economic condition, they sometimes try to reclaim their dignity

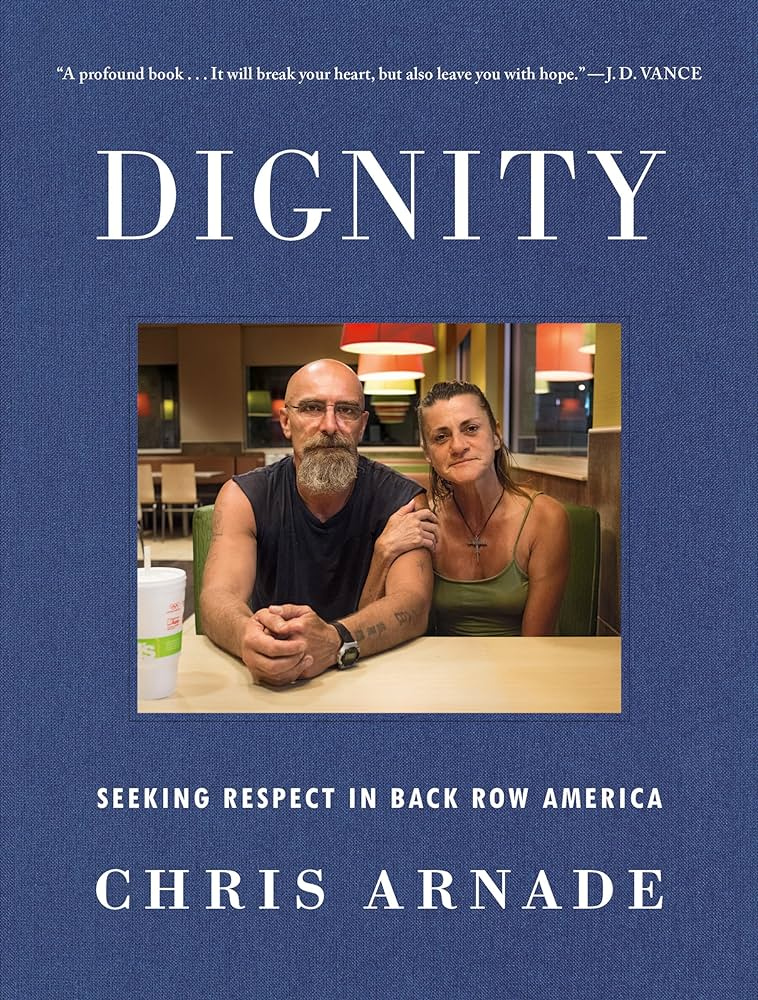

A review of Dignity: Seeking Respect in Back Row America by Chris Arnade. Sentinel, 304 pages (June, 2019)

Chris Arnade began his career not long after Michael Lewis retired from bond trading to write his 1989 memoir Liar’s Poker. A physics PhD from Johns Hopkins, Arnade was one of the highly educated new breed of traders, and managed to stay two decades instead of two years like Lewis. But he found his way (or was ushered) to the exit a few years after the mortgage-backed securities that Lewis wrote about blew up the financial system.

The financial crisis caused Arnade to reevaluate his life and to begin chronicling inequality and poverty in America as a journalist. In parts travelogue, sociological observation, and personal memoir, Arnade presents his work as written articles and pictures, and the end result is reminiscent of Jacob Riis’s nineteenth century classic How the Other Half Lives. Arnade’s new book is called Dignity: Seeking Respect in Back Row America, and, within its pages, Arnade shows the explanatory limitations of the spreadsheets he used to understand the world when he worked on Wall Street.

Dignity isn’t for the faint of heart. The discussions and photographic depictions of crushing poverty and addiction are often painful. Arnade initially makes his way to the Hunts Point neighborhood of the Bronx on long walks after work, and winds up talking to drug addicts and prostitutes. He wins their trust, and they tell him their stories. Then, after his job ends, he drives around the country to other down-and-out areas to see if what he finds there jibes with what he’s learned in Hunts Point. Arnade goes to places like Selma, AL, Bakersfield, CA, Gary, IN, Portsmouth, OH, Cairo, IL, and Amarillo, TX—anywhere nobody else wants to visit because of the economic blight, drugs, and general social dysfunction. These places contain what Arnade calls “back row kids” or people who didn’t excel at school and who were not able to use education to catapult themselves into better circumstances.

That is a helpful way to describe the economic and political split in the country, and in Arnade’s telling it sounds like we’re living in a meritocratic system gone berserk. Front row kids are well educated, live in big cities, and have jobs where intellectual capability is required and remunerated. In school, they were “always eager to learn and make sure the teacher knew they were learning.” Back row kids, by contrast, “couldn’t or didn’t want to leave their town or their family to get an education at an elite college…[or] didn’t take to education, because it wasn’t necessarily their thing or because they had far too many obligations—family, friends, problems large and small—to focus on studying.”

Back row kids used to be able to walk out of high school with diplomas and get good-paying factory jobs with benefits that allowed them to live decent lives and educate their kids. Now, however, with labor offshoring and technological advances, those jobs are gone. The front row kids have given Wall Street the lower labor costs it always wanted. Corporate profits, GDP, and the stock market are all higher, but there is no mathematical variable that captures community destruction and the back row’s loss of dignity in the front row’s efficiency equations. And since there is no mathematical accounting for dignity, not many thought about it until the presidential election of 2016, the result of which, it’s worth noting, Arnade does not favor, but correctly predicted.

A consequence of economic blight, in Arnade’s view, is the drug epidemic. He draws a direct line from deprivation to addiction when he writes, “[underachievement] is a stigma that can lead to drugs.” Many people with whom he speaks in crack houses say, “I am dumb,” or “They said I was dumb.” But Arnade is also aware that many drug users have suffered severe psychological trauma, such as physical and sexual abuse and neglect, as children. Surely, economic hardship increases the probability of neglect, but neglect and abuse—and resulting addiction—sadly occur at all socioeconomic levels.

Arnade himself admits to his own difficulty with alcohol and the tranquilizer Xanax, which, since he’s not economically deprived, seems to contradict his hypothesis that drug abuse is a consequence of poverty. He describes himself as fitting the definition of an addict, drinking too much and scoring pills on the street in his early treks to Hunts Point. This gives him a kind of street cred, although eventually he’s able to quit. But we never learn why he started (except for maybe disenchantment with work and a sense of being lost in his life) or why he stopped. One can speculate that as he moved away from Wall Street and found surer footing in the work that eventually resulted in this book, a renewed sense of purpose and meaning helped to sustain him. It’s possible that revealing part of his own story is Arnade’s nod to the complex causes of addiction, but it’s hard to know.

Addicts—and human beings, generally—need community. Much of Dignity is dedicated to showing where people in back row America find it when they can overcome a tendency to isolate themselves. Arnade uses the word “dissociate” (to disconnect mentally or emotionally from thoughts, memories, feelings, or a sense of identity) incorrectly here in discussing that tendency. Nevertheless, the reader gets the message—poverty is shameful and doesn’t make you want to be around others. But being alone is painful, so addicts find solace not only in the drugs they use, but also in the community crack houses and heroin dens provide. Without glorifying drug use, Arnade observes that drug dens serve as the worst communities’ bars.

The other two places where back row America congregates (less dangerously) are McDonald’s and church. In many blighted areas, the local McDonald’s serves as the community center or even the town square. Down-and-out or homeless people can sit and nurse their coffee all day undisturbed. The McDonald’s hosts everything from morning groups of retirees gathering to gossip to people playing dominoes or even bingo. There aren’t a lot of rules governing behavior at McDonald’s, making it more pleasant for many than a shelter. It’s a place to escape the heat or cold, and it has WiFi and sockets to charge a phone. As Arnade says, “McDonald’s was one of the few spaces in Hunts Point open to the public that worked.” McDonald’s is the most functional place in America’s most dysfunctional communities.

Arnade is also warmly welcomed by strangers in their churches (one of which occupies a former Kentucky Fried Chicken), regardless of the predominant race of the parishioners or whether he’s unkempt. Like McDonald’s, churches—or at least those involved in some community outreach—are among the few places that accept people as they are. Arnade is surprised to find that a transgender addict named Shelley, who has lived on the streets since she was a teenager, doesn’t blame religion for being run out of her community, and is herself religious. Her rosary is her “symbol of peace and tranquility… [It] reminds me that there is something greater out there, greater than this earth and its people. Something better than this.” It’s not quite that religion doesn’t judge, but “churches understand the streets, understand everyone is a sinner and everyone fails.” Churches also offer a path out of addiction because they provide hope. “This is how it is on the streets,” says Arnade. “Faith is the reality and a source of hope. Science is the distant thing that doesn’t necessarily do much for you.”

When it comes to race, Arnade repeats the theme of being fooled by numbers, completing his critique of the front row’s obsession with spreadsheets filled with data. On his visits to Selma and the northern part of Milwaukee, African Americans repeatedly tell him that the racism they encounter is only different to that of the Jim Crow era South insofar as it is more covert. This prompts Arnade to reflect on his own experience growing up in a small town in Florida, and he says, “You can ignore data [suggesting that racism has receded], but you can’t ignore when friends are thrown against the wall by police for nothing but their skin color, while the police don’t bother you.”

There aren’t easy solutions to the problems Arnade describes, and he doesn’t try to force any. He only asks us to consider whether boosting GDP, corporate profits, and the S&P 500 are worthy ends if they come at the expense of so many social problems and so many people’s dignity. Arnade defines dignity differently to the philosopher Immanuel Kant, for whom the word was so important. Kant used the word in connection with his moral theory: Human beings should act as if what they do were a universal law and treat themselves and other human beings as ends. Because human beings are capable of morality, they have dignity, according to Kant. But that view makes it’s difficult to excuse depravity as a consequence of economic deprivation. After all, everyone has the ability to think about whether an action could be a universal law and whether they’re treating someone as a means or an end.

Some reflection on Kant can provoke questions about whether Arnade expects too little of the people and places he visits, although it’s impossible to deny they’ve been dealt an unattractive hand. Arnade mostly means that the front row is robbing the back row of its dignity by inflicting economic hardship on it, but it’s not always clear if the economic hardship or the behavior to which it can lead represents the loss of dignity. It’s also possible the front row sacrifices some of its dignity too by inflicting pain on the back row, but Arnade doesn’t make a full case for that. Arnade also tries to show that even in its compromised economic condition, the back row retains some dignity, as he understands it. Back row people who want to stay close to their families at the expense of an education at a good college and a job in a big city display a kind of dignity or virtue in their dedication to others or their communities. Arnade may overstate the extent to which not leaving a small town is a choice, of course.

Dignity also has something to do with pride and identity, according to Arnade. If members of the back row lack dignity because of their economic condition, they sometimes try to reclaim their dignity by identifying with members of their racial group. That may sound overly simplistic, but it’s what Arnade observed in the run-up to the 2016 election in countless communities economically impaired because of factory closings. This may also be the most dangerous political outcome of the turbulence caused by the spread of automation and the consequent loss of economic opportunity.

Michael Lewis’s critiques of Wall Street have never stuck partly because he made the rogues and misfits of Liar’s Poker and The Big Short so lovable and partly because he remains dedicated to spreadsheet rationality. Arnade indicates that he might well choose the same path if he had the chance to live his life again—out of his hometown, into a PhD program, and onto a trading desk. But his anecdotal tour of the American underclass raises thought-provoking questions about the limits of spreadsheet rationalism and its consequences for society’s most disadvantaged.