Hypothesis

Considering the Male Disposability Hypothesis

A 2016 study published in Social Psychological and Personality Science found that people are more willing to sacrifice men than women in a time of crisis and that they are more willing to inflict harm on men than on women.

In her analysis “Women and Genocide in Rwanda,” the former Rwandan politician Aloysia Inyumba stated that “The genocide in Rwanda is a far-reaching tragedy that has taken a particularly hard toll on women. They now comprise 70 percent of the population, since the genocide chiefly exterminated the male population.”

In a 1998 speech delivered before a domestic violence conference in El Salvador, former US senator and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said that “Women have always been the primary victims of war. Women lose their husbands, their fathers, their sons in combat.”

These statements are illustrative of a wider trend of “male disposability.”

What is Male Disposability?

“Male disposability” describes the tendency to be less concerned about the safety and well-being of men than of women. This might sound surprising given the emphasis in contemporary Western discourse on the oppression of women by men. How is it possible that societies built by men have come to consider their well-being as less important? But embedded in this kind of question are simplistic assumptions that flatten a good deal of complexity.

A 2016 study published in Social Psychological and Personality Science found that people are more willing to sacrifice men than women in a time of crisis and that they are more willing to inflict harm on men than on women. In 2017, an attempt to replicate the Milgram experiment in Poland provided some (inconclusive) evidence that people are more willing to deliver severe electric shocks to men than to women:

“It is worth remarking,” write the authors, “that although the number of people refusing to carry out the commands of the experimenter was three times greater when the student [the person receiving the ‘shock’] was a woman, the small sample size does not allow us to draw strong conclusions.”

A 2000 study found that among vehicular homicides, drivers who kill women tend to receive longer sentences than drivers who kill men. Another study found that, in Texas in 1991, offenders who victimized females received longer sentences than those who victimized males. There is at least some evidence that “women and children first” is a principle still employed during rescue efforts in natural disaster zones. Some social scientists have also noted that the media is more likely to focus on female victims than male victims. This is especially true for white female victims.

It is interesting to consider the above in light of the following: Men are more likely to be murdered than women and, in some cases, they are more likely to be physically assaulted. In most countries, men are more likely to die from suicide, they are more likely to be homeless, they’re more likely to be killed by the police, and they are more likely to work in dangerous jobs. Some countries also specifically criminalize male homosexuality, and male homosexuals seem to be more likely to be victims of hate crimes. The wartime rape and sexual abuse of men are also believed to be more prevalent than most people realize.

That's a weird way of saying 75% of homeless people are men. #equality #feministlogic pic.twitter.com/VNsJy9mliW

— ಠ_ಠ (@AtheistLoki) June 5, 2016

Despite all this, the media appear to focus overwhelmingly on violence against women and whole international organizations and movements have been founded to end violence against women and girls. You will be incredibly hard-pressed to find similar resources when it comes to ending violence against men. Of course, all this doesn’t mean that men are always more disposable than women. There are indeed circumstances in which women are treated as more disposable, such as the disproportionate abortion of female fetuses in countries like China and India. However, although this complicates the Male Disposability Hypothesis, it does not invalidate it.

Why Violence against Men Is Often Ignored

When pressured to admit that violence against men is largely normalized and ignored compared to violence against women, many respond by trying to justify the imbalance. For example, some contend that violence against women is “gendered” and should therefore be taken more seriously. However, a lot of violence against men is also gender-based. During the Rwandan genocide, it was mainly men and boys who were targeted for murder because of their gender. The gendered nature of the killings was largely downplayed, however. During the Srebrenica massacre, men and teenage boys accounted for the vast majority of the victims. Sexual abuse against men is also believed by many social theorists to be an attack on masculinity intended to demoralize victims by making them feel incapable of fulfilling the male role. Even if we were to accept that violence against men is not gendered, that would not justify ignoring the more common and widespread victimization of men and boys.

A related argument holds that because men are usually victimized by other men, it is less important than violence inflicted on men and women arbitrarily. For some reason this is not considered “gendered” violence, because it is assumed that men cannot target other men for being men. This line of thinking is highly unsatisfactory. Men tend to be quite competitive with other men and there is at least some evidence that women like women more than men like other men. When a man rapes or castrates an enemy during wartime, it is not just a random act of violence, it is a direct attack on masculinity.

A third excuse, usually not explicitly stated but strongly implied, is that men somehow “deserve” to be victimized. After all, if men are the majority of the perpetrators, then it is somehow just that they get a taste of their own medicine. In a 2004 post about the violence in and around the Mexican border town of Ciudad Juárez, political scientist Adam Jones quoted an article by Debbie Nathan in the Texas Observer as follows: “Slaughtered, butchered and scorched male corpses are found far more frequently than women’s bodies are. [But] few seem surprised, much less outraged, by this male-on-male carnage.” Drawing on the arguments above, Jones went on:

The standard operating procedure in feminist scholarship and activism dictates that when a complex social phenomenon like murder is addressed, certain rules must be followed. Briefly put, trends that evoke concern and sympathy for women—in this case, the sharp rise in women’s murder rates in Ciudad Juárez—must be carefully separated out and presented in isolation. Data that threaten to offset or contextualize the portrait, perhaps to the detriment of an emphasis on female victims, must be ignored or suppressed. Hence the invisibility of the nine-tenths of Juárez’s murder victims who are male. […] This feminist strategy reflects, and exploits, cultural convictions about men that are nearly universal. Men are seen as the “natural” victims of homicidal killing, for two main reasons. In part, this is because in most cases, men’s killers are other men—and we all know that “boys will be boys.” Second, men are viewed as implicated victims.

In other words, men are generally perceived as responsible for their own victimization on some level. Women, on the other hand, are largely innocent so violence committed against them is a more serious crime. This is merely a doctrine of collective guilt and punishment.

What Are the Causes?

The question is, why does society frequently appear to care more about the well-being of women?

Social theorists might argue that men are expected by society to be more resilient and self-reliant so they’re often viewed as lesser victims. Women, on the other hand, are perceived as comparatively weak and vulnerable and therefore in greater need of protection, in the same way that adults feel protective towards children. However, feminists would no doubt counter that this attitude is simply evidence of benevolent sexism and female infantilization.

Others speculate that humans—especially males—evolved to be more protective of women. At least one study conducted by evolutionary psychologists has found that men are more willing to make the anti-utilitarian choice to let three members of the same sex die in order to save one member of the opposite sex, especially when there are fewer potential sexual partners. This suggests that men’s willingness to sacrifice men to save women may be tied to their need for sexual and reproductive success. Scientist David Brin argues that women in many ways physically resemble children more than men do (neoteny) and that they evolved that way to inspire protective impulses in men. However, this doesn’t explain the findings of other studies which suggest that women are also more willing to sacrifice men. Another possible explanation is that both men and women evolved to be protective of women because one man can impregnate several women, while a woman will usually only bear one child at a time, so it makes sense for societies to keep women safe so they can reproduce.

It’s hard to say which theory is more accurate or if all of them have some basis in truth. There is shockingly little research on the subject. Researching male victims is not compelling precisely because men are disposable “lesser victims” and male disposability tends to be reinforced by this tendency to ignore the phenomenon.

Is It Possible to Eliminate Male Disposability?

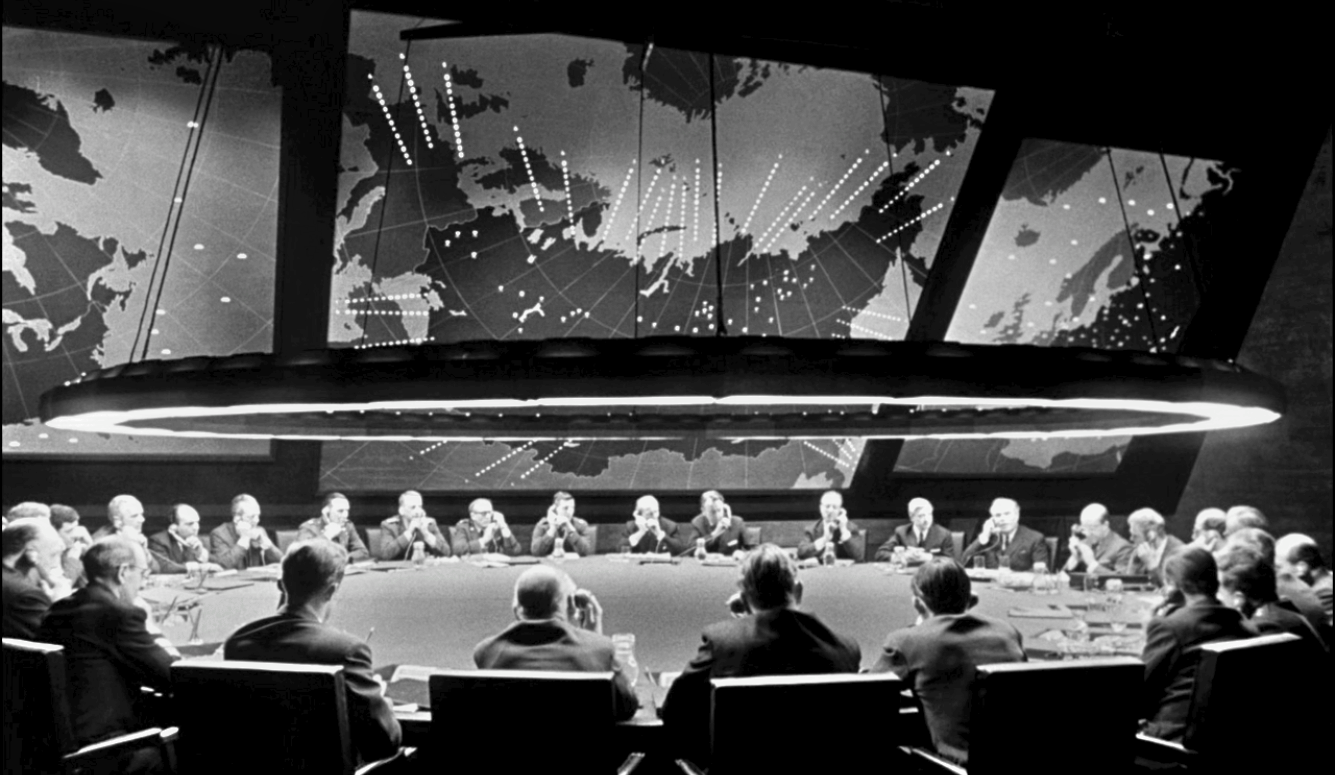

It is not possible to say for sure given the available data whether male disposability is partially evolved or purely the result of socialization. Even if we were to assume that male disposability is, on some level, instinctual, it doesn’t mean that society cannot minimize it. The real question is, do we want to eliminate male disposability? Do we want to send more women into combat? Do we want to have more women in dangerous jobs? Do we want to focus on male and female victims equally? I think this kind of equality is a laudable goal, but it will surely meet some resistance from society. Men themselves are often hesitant to see themselves as victims, traditionalists (male and female) would resist such a challenge to gender norms, and many feminists would resist the idea that male victims should receive greater attention.

What Does Male Disposability Mean for Feminism?

Male disposability does pose a challenge to certain feminist assumptions, but it doesn’t inherently have to be an argument against feminism. There have been cases in the past where feminists have been hostile to attempts to address male victimization, mostly because they fear that shifting the focus toward male victims will further marginalize female victims of male violence.

However, to generalize about all feminist theory in this way would be unfair. Many prominent feminists, like bell hooks, have argued that what they call “patriarchy” can be harmful to men. It is also generally accepted by feminists that male victims of sexual abuse can be marginalized under the gendered norms they oppose. Feminist attitudes towards male issues can be far from perfect and criticisms of feminism by some men’s rights activists are not without merit. But I believe it is both possible and necessary to find some common ground. It is hard to argue that feminism is not needed when one looks at the victimization and oppression of women worldwide. However, oppression is not a zero-sum affair—addressing the oppression of women does not require us to disregard the victimization of men.