recent

The Abortion Issue Isn’t About ‘The Patriarchy’

The debate over the morality and legality of abortion is one of the most divisive and enduring issues in American public life.

On Wednesday, Alabama Governor Kay Ivey signed into law the most restrictive ban on abortion in the United States. The legislation bans all abortions—even in cases of rape and incest—with exceptions being offered only to pregnant women whose lives are in serious danger. Medical practitioners who perform abortions will be liable for felony charges, which carry a potential sentence of up to 99 years in prison. (Mothers will not be liable.) Alabama has gone even further than other states that recently have passed anti-abortion laws, since those laws ban the practice only after a heartbeat is detected—usually at six or eight weeks into a pregnancy.

The Guardian’s headline on the Alabama story—These 25 Republicans—all white men—just voted to ban abortion in Alabama—channelled a dominant social-media meme by putting gender front and centre. Twitter and Facebook were rife with claims that Alabama’s bill, like other anti-abortion laws, was really all about men attacking women’s rights and bodily autonomy.

Perhaps the most succinct articulation of this view goes back to 1971, when feminist Gloria Steinem famously claimed: “If men could get pregnant, abortion would be a sacrament.” Her words positioned the issue of abortion as a gendered power struggle, according to which the act is seen as controversial only because it’s something women do. Insofar as it’s possible to imagine a world in which men were the ones who bore children, Steinem contended, the right to abortion would be celebrated (or at least scrupulously protected).

There are days I wonder whether white Republican men fear women, hate women, or believe they simply have the right to control women. Then there are days like today, when it’s clear it’s all three. #Alabama #VoteThemOut

— Greg Hogben (@MyDaughtersArmy) May 15, 2019

But this approach fundamentally mischaracterizes the reality of the abortion debate, and misconstrues why most pro-life people oppose abortion rights.

The debate over the morality and legality of abortion is one of the most divisive and enduring issues in American public life. Roughly the same number of Americans describe themselves as pro-life as they do pro-choice. For a sizeable proportion of the U.S. electorate, the question of whether or not a candidate is pro-life is the single most important issue that determines their vote. Forty-six years after Roe vs Wade was decided, 21 percent of pro-life voters still say they would not vote for a candidate who did not share their views on abortion. And so Donald Trump’s pro-life statements in his 2016 presidential campaign are likely to have played a role in his election win over the pro-choice Hillary Clinton.

Liberal feminists who argue that the fight for abortion rights is primarily a fight against an oppressive patriarchy are apt to point to the fact that in Alabama and other states that have passed anti-abortion laws, male legislators dominate politics. Many liberal feminists even argue that men shouldn’t be permitted to participate in the debate over abortion at all, since they will never be in a position to seek one themselves.

However, polling evidence suggests that American men, overall, are just as likely to be pro-choice as women. True, women are more likely to express support for abortion rights. But, surprisingly, women also are more likely to express opposition. Democrat women are slightly more likely than Democrat men to be pro-choice, but Republican women are more likely than Republican men to be pro-life. In other words, there is no major fault line in the abortion debate between men and women.

There is a very clear divide when it comes to religious belief, however. Seventy-seven percent of American atheists and agnostics describe themselves as pro-choice, with only 19 percent identifying as pro-life. By contrast, 75 percent of surveyed respondents who attend religious services on a weekly basis are pro-life, while only 20 percent are pro-choice. It’s no coincidence, then, that in America, the most vocal opponents of abortion rights tend to be Christians.

A feminist might respond with the argument that Christian voters’ support for pro-life positions is merely a symptom of the patriarchal streak embedded within religious doctrine more generally, which has always lent itself to implementing control of women’s lives. But Islam, which in many respects is regarded as more patriarchal in outlook that Christianity (especially when it comes to codes of conduct and dress), is comparatively more supportive of women’s right to abortion than Christianity. Both Sunni and Shia traditions typically prohibit abortion only after 120 days, as this is thought to be the point of “ensoulment,” at which time a human fetus develops its own right to life.

Most traditional Christians, by contrast, view conception as the point at which a human fetus—or, more accurately, a human embryo—develops an inviolable right to life. For these pro-lifers, the central issue tends to be relatively straightforward: Abortion is viewed as reprehensible because it is seen as the intentional ending of human life, tantamount to murder. This isn’t something that can be chalked up to “patriarchy,” and it is false to attribute such attitudes to the desire to control women’s freedoms.

The vast majority of Americans who support a pro-life position don’t dispute that women should have control over their bodies. What they do dispute is that bodily autonomy should include the right to end the life of a human fetus or embryo, which they view as morally equivalent to your life or mine.

This should be clear from the Catholic Church’s sustained opposition to embryonic stem cell research. Research of this kind doesn’t involve the controlling of women or the policing of their reproductive health, yet it has been opposed purely on the grounds that it involves the destruction of human embryos. It’s one thing for liberal feminists to disagree with the pro-life position, but it’s another to pretend that the moral status of the fetus isn’t the central point of concern for those who oppose abortion.

Claiming that a human embryo is “just a clump of cells” without significant moral worth might seem plausible in regard to the first few weeks after conception—which is why over 60 percent of all Americans support the legal right to abortion in the first trimester. But that support drops substantially—to 28 percent—when it comes to the second trimester. And only 13 percent support so called “late term” third-trimester abortions.

Interestingly, the 60 percent of Americans supporting the right to first-trimester abortions includes a small but significant percentage of the 48 percent of Americans who call themselves pro-life. So there is some shared ground at play. But that shared ground shrinks when activists stake out unrealistic positions: When liberal feminists focus their campaigning around the themes of complete bodily autonomy, including the right to late-term abortions, the polling data suggests they may be pushing some people away from a moderate pro-choice position toward a pro-life position.

Those who support abortion rights in some form should be prepared to argue their case on the terrain that pro-lifers have traditionally claimed as their own: the apparent right to life (or lack thereof) of a human fetus during pregnancy. Continuing to assert a woman’s bodily autonomy is unlikely to progress the abortion debate, because very few people dispute that women should be in charge of their bodies. Nor does it advance the debate to focus on whether it is men or women who are passing laws in this area, since it tends to be religious viewpoint, not sex, that is correlated with attitudes.

Alabama’s new law has exacerbated a divide that has existed in the United States for generations, and which won’t be bridged soon. Though it is guaranteed that people will continue to disagree about abortion, we should at least direct the argument over the issue to the real issues that separate us, not to slogans that have little bearing on what anyone truly thinks or feels.

Andrew Glover is a sociologist. Follow him at @theandrewglover.

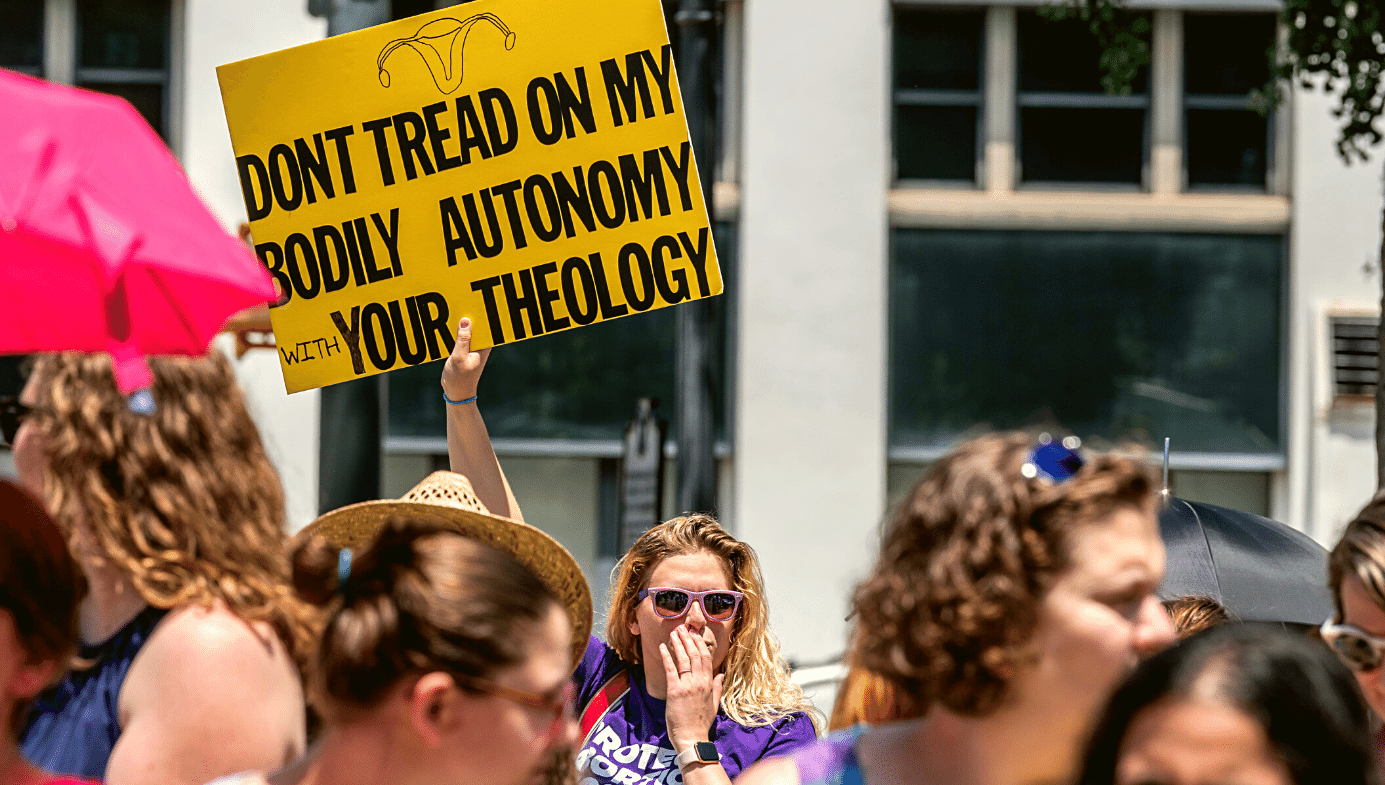

Featured image: Protesters at the International Women’s Day March in Barcelona, March 8, 2017.