recent

In the Culture Wars, Be a Sancho Panza, Not a Don Quixote

Racists themselves succumb to a version of Don Quitoxe’s delusions when life becomes overwhelming or tumultuous.

“Look there, friend Sancho, and behold thirty or forty outrageous giants, with whom, I intend to engage in battle, and put every one of them to death…for, it is a meritorious warfare, and serviceable both to God and man, to extirpate such a wicked race from the face of the Earth.”

“What giants do you mean?” said Sancho Panza.

“Those you see yonder,” replied his master, “with vast extended arms; some of which are two leagues long.”

“I would your worship would take notice,” replied Sancho, “that those you see yonder are no giants, but wind-mills; and what seem arms to you, are sails; which being turned with the wind, make the mill-stone work.”

“It seems very plain,” said the knight, “that you are but a novice in adventures.”

Miguel de Cervantes’ 1605 novel The Ingenious Nobleman Sir Quixote de La Mancha is about a middle-aged nobleman who spends his leisure time reading tales of knight-errantry. Well-bound tomes of epic romance cover his library walls. Chivalrous quests of valiant knights vanquishing evil foes invade his imagination. He devours the tales until, one day, “the moisture of his brain was exhausted” and “at last he lost the use of his reason.” To the dismay of his family, Quixote then sets off on an aged horse and dedicates his life to wandering the countryside as a gallant knight, confronting wickedness, performing virtue, and conforming in every way he can to the values of the knights populating the stories he read.

Everyday people whom Quixote encounters are transformed into enemies. Unsuspecting townsmen fetching water for their horses are mauled on suspicion of thievery. A group of merchants, failing to proclaim the beauty of a woman they had never met, are denounced as wretches and blasphemers. In his most famous sally, Quixote identifies a field of windmills as giants, engages them in battle, and is struck to the ground by a rotating sail.

Fast forward four centuries. In late 2018, the independent, non-profit New York-based research institute Data and Society released a report entitled Alternative Influence: Broadcasting the Reactionary Right on YouTube. On paper, the report certainly appeared authoritative. Data and Society itself boasts of having received support from dozens of respectable groups, from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to The New York Times to UNICEF. Their professed goal is to identify “thorny issues at the intersection of technology and society, providing and encouraging research that can ground informed, evidence-based public debates.” In every way that I can determine, Data and Society presents itself as a perfectly ordinary mainstream left-leaning research institute.

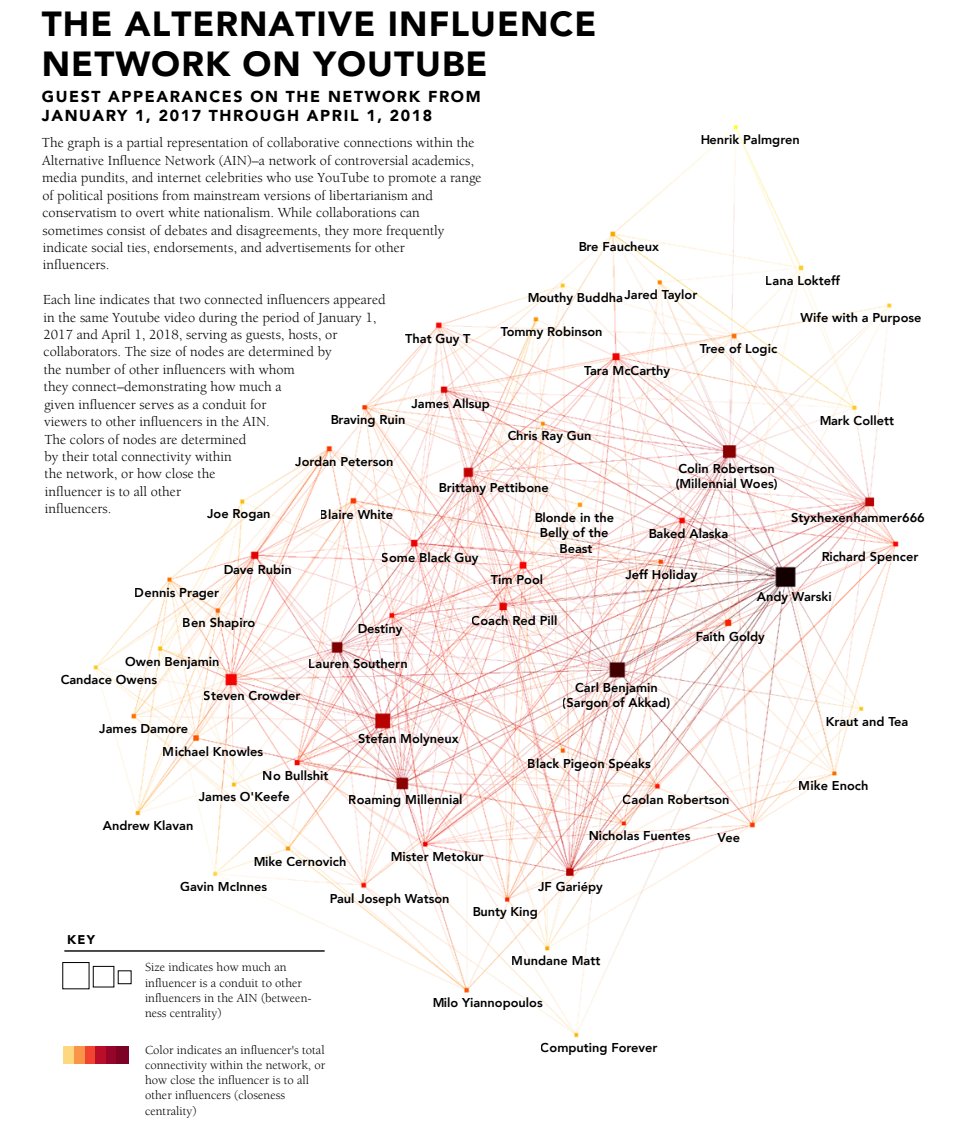

In Alternative Influence, Data and Society researcher Rebecca Lewis purported to identify a network of “political influencers”—a group of 65 named public figures whose work, the report warns, can lead unwary viewers to embrace “a range of political positions, from mainstream versions of libertarianism and conservatism, all the way to overt white nationalism.” Noting the smooth too-easy transition from conservatism and libertarianism to white nationalism, Lewis explains that “social networking between influencers makes it easy for audience members to be incrementally exposed to, and come to trust, ever more extremist political positions.” What’s worse, Data and Society warns us, “YouTube incentivizes their behavior,” even permitting the listed personalities to “cultivate alternative social identities and use production value to increase their appeal as countercultural social underdogs.”

Go down the list of these gateway “influencers,” and you do find some genuinely dangerous people, such as self-professed white nationalist Richard Spencer. Fair enough. But interspersed among these names are people who seemed, at least to me, suspiciously out-of-place, like University of Toronto Psychology professor and New York Times best-selling author Jordan Peterson, comedian and talk show host Dave Rubin, and podcast host and stand-up comedian Joe Rogan—all names you might encounter in the window display of your local book store.

Accompanying this array of names in the report is a web of interlinking lines portraying vectors of influence from one figure to the next, a dizzying constellation of alleged hate. Land on a single node in this diagram, the graphic suggests, and one becomes entangled permanently in an all-consuming web of hateful ideology.

The term that Lewis uses to describe many of these figures is “alt-right.” It is employed repeatedly throughout the report as a catch-all descriptor for people with supposedly dangerous views, but never once does Lewis define it. The closest she comes to a definition is implicitly, through a footnote to a self-declared social-justice activist group, which presents “alt-right” as a species of “white nationalism.” If Lewis is to be believed, all 65 people she identifies are either proponents of, or gateways to, this white nationalist creed.

As noted above, this would seem to include Peterson, whose most recent book has sold more than three million copies and was published by no less a mainstream outlet than Penguin Random House. It also includes Rubin, who began his comedy career as an intern under Jon Stewart for The Daily Show, and once won LA Weekly’s “Funniest Twitter” award. And it includes Rogan, whose most recent stand-up show was produced and aired by Netflix just last year.

So: We have here a benign-sounding, if somewhat obscure, research institute casually accusing various popular, mainstream public figures of being gateway agents to an ideology commonly associated with genocide and slavery. How can this be? Are we so blind, we subscribers to Netflix, we habitués of Barnes & Noble? Are we akin to the Germans of the 1930s who ignored the warning signs? Has our society become so degraded that cultural staples such as Penguin Random House, Comedy Central and Netflix are now helping to spread dangerous ideas, like a contagion infused into a defenseless host society?

While this exercise in social panic may appear bizarre to ordinary readers, it will not appear especially unusual to anyone who spends any time at all in a Communications department at certain universities, or in certain areas of Twitter, where the portrayal of such pundits as agents of alt-right evil is a matter of casual consensus. If anything, in fact, Lewis cast her net too narrowly for this crowd, which often will throw in everyone from Harvard University professor Steven Pinker to Quillette’s own editors and writers, myself included. (Not so narrow, mind you, that she didn’t manage to include a few Jews—including James Damore, Sam Harris and Ben Shapiro. Lewis appears okay with the cognitive dissonance required to accuse Jews of flirting with white supremacy.)

In late 2018, I sat down with my former Master’s thesis advisor, an academic at Concordia University who had presented with Data and Society at an academic event in Montreal. Having read the 2018 report, I asked him flat out whether he thought I was a white supremacist simply on the basis that I enjoyed listening to Joe Rogan’s podcast. He responded as follows: “I don’t want to say, because the definition is always changing. Can’t we just disagree about this?”

This is what my life had come to. Someone who had volunteered to guide my thesis work could not fully swear off the possibility that I was a servant of white supremacy. Like Goebbels. And merely on the basis of my podcast preferences.

It is not that my advisor is a bad person, or even unique in his views. Many progressives throw terms such as Nazi and white supremacist around now like confetti. White supremacists proliferate throughout society, we are led to understand, occupying the highest stations of cultural and intellectual life, apparently undetected by their colleagues. The danger is spreading. The tide is rising. And yet, Harvard keeps employing them. Netflix keeps producing them. Penguin Random House keeps publishing them. And millions of people, from various walks of life, keep enjoying their work.

There seems to be a discrepancy here. If all these public intellectuals are as dangerous as these claims suggest, why are we not progressing toward a dystopia—something like Nazi Germany, or Panem from The Hunger Games? Canada, my own country, recently was cited in a Social Progress Imperative report as being among the most progressive countries in the world, according to an analysis of factors that include personal rights, personal freedoms and choice, and inclusiveness. That seems inconsistent with the state of high anxiety that animates Alternative Influence.

There are, of course, dangerous people in the world, spreading genuinely dangerous ideas and doing real damage. Among these are actual white supremacists like the gunmen who shot and killed 50 people at the Linwood Islamic Centre and the Al Noor Mosque in Christchurch, New Zealand. These concerns are real, and need to be continually confronted. But the existence of such concerns does not explain why mainstream conservatives, libertarians and even classical liberals are now being lumped in with the worst elements of humanity. Why are so many seemingly respectable intellectuals and institutions tilting at windmills?

Don Quixote, I believe, may provide something of an answer. The novel is animated by the juxtaposition between Quixote’s old world of faith and certainty, and the complex modern age that Cervantes and his contemporaries were beginning to embrace in the 17th century.

Eventually, over time, the transition from the old world to the new freed Europe from the strict dogmatism of the church, something for which most of us are quite grateful. But as any cursory reading of European literature over the next century or four could affirm, a world without an overarching God-given meaning can be a terrifying place. Easy, transparent notions of right and wrong have a romantic appeal. They provide order and meaning in life. They create a singular path to follow, promising a heavenly utopia at the other side of death. Quixote’s world, like our own, bombarded people with too many voices, too much noise. Seen in this light, Quixote’s madness is a symptom of his hunger for a simpler place, with a simple moral code providing salvation and a clear strategy for thwarting evil.

So Don Quixote chooses to live in a world of his own imagination. Like any good Christian knight, he sees himself as a “redresser of grievances, a remover of wrongs and injuries, a corrector of abuses, and a discharger of duties.” And there is never any doubt as to what those wrongs and duties are. Members of the modern progressive movement, I would argue, often see themselves much the same way.

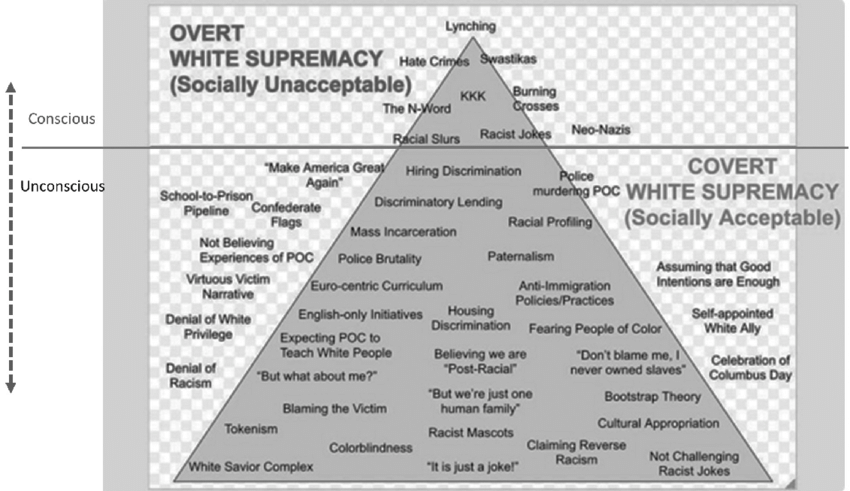

Consider the image above, a visual aid provided courtesy of Dwight D.L. Turner, Senior Lecturer at the University of Brighton. It was included in a peer-reviewed academic paper titled You Shall Not Replace Us!’ White supremacy, psychotherapy and decolonization. Take a look at some of the items listed. Ever emphasized our common humanity instead of the different colours of our skin? Ever failed to challenge a racist joke, say at a party? Ever disbelieved, even once, a single experience communicated by a person of colour? You are apparently on the path to white supremacy.

Racists themselves succumb to a version of Don Quitoxe’s delusions when life becomes overwhelming or tumultuous, and spuriously organize society into binary categories of us and them. But progressives do this, too. This notion of white nationalists and neo-Nazis skulking everywhere seems to result from the urge to streamline society, neaten it up, clarify its ideological categories, make everything luminously simple. Either you are an ideal citizen, or you are out. Either you are an active knight in the progressive cause, or you belong on a list.

But the real world, as Cervantes knew, is not that simple. Someone can be skeptical of the existence of “non-binary” genders without being a transphobe. Someone can suggest that women might, in general, be inclined to possess different interests than men without being a misogynist. Someone can think that things in the western world have been getting progressively better on the whole for centuries without being a white supremacist. These opinions are not indicative of a moral deficiency. These opinions may be correct, or they may be incorrect. They may also be changeable, or nuanced, or based on differing life experiences. The people holding these varied opinions are not thieves or blasphemers or giants. They are your fellow townsfolk.

The biggest danger of Quixotism, to my mind, is that people will be turned off the entire progressive project. All the antagonistic jargon and lists and simple black-and-white morality and name-calling and moral self-righteousness reads as madness to people who might otherwise be sympathetic or potentially persuadable to progressive causes. If progressives want to make headway, frankly, they need to get down off their high horses.

The truest and most productive path for all of us is that offered by Sancho Panza, whose role is to state simple truths, none more important than that “those you see yonder are no giants, but wind-mills.”