Activism

When Children Protest, Adults Should Tell them the Truth

The climate debate is a complicated one. It requires the careful weighing of interests and trade-offs, not the uncompromising fanaticism of an absolutist.

Last Friday, children in over 120 countries skipped school to follow the example of a Swedish 16-year-old who has become an international icon of climate change activism. Greta Thunberg’s extensive media coverage has made her a familiar figure—large almond-shaped eyes, brown plaited hair, serious expression, and diminutive stature. This month she was named Swedish Woman of the Year and also nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by three socialist Norwegian MPs. She has spoken to world leaders at the United Nations Climate Change Conference and she has delivered a talk to the World Economic Forum in Davos. Her achievements are extraordinarily impressive for a young girl suffering, by her own account, from several mental health issues.

Thunberg is inspiring thousands of schoolchildren to join her skolstrejk för klimatet, or “school strike for the climate.” She has dedicated every Friday to this cause since August 2018, following her first full-time strike. Inspired by the teen activists in Florida who organised the March For Our Lives in response to the shooting at Parkland school, Thunberg’s protests outside the Swedish Parliament and clever speeches—a TedxStockholm talk in November 2018 and rallies in Hamburg and London—have brought a fresh face to the environmental movement. Her activism has received uncritical adulation from public figures and world leaders, including Germany’s chancellor Angela Merkel and US Democratic Socialist Bernie Sanders, who tweeted:

There’s no doubt Thunberg is an eloquent, courageous, and precociously intelligent activist and an example to young people who care about the earth and its future. But it is precisely because she is such a popular and effective campaigner that it is important to scrutinise her message. In his Spectator column, Toby Young did just that and concluded that her message is nonsense:

Greta Thunberg is everywhere, appearing at Davos, giving a TED talk, speaking at the UN Climate Conference in Katowice, and her message is always the same. Western governments are doing nothing to combat climate change. She isn’t saying they’re not doing enough. No. She claims they’re not doing anything. “Everyone keeps saying that climate change is an existential threat and the most important issue of all and yet they just carry on like before,” she says in her TED talk. “You would think the media and every one of our leaders would be talking about nothing else, but they never even mention it.”

Never mention it? One of the placards often held up by climate change protesters says there’s no “Planet B,” but Greta does appear to have been living on another planet for the past 16 years.

Criticising a teenage girl with good intentions will not make a person especially popular, and Young’s Twitter mentions were duly filled with scornful critics. “I’ve never known,” remarked one tweeter, “a grown man to get triggered so easily by a child.” The medium of childlike innocence has become the environmental message, and been placed on a pedestal above criticism. But, given her own insistence on the vital urgency of the matter at hand, heartwarming optics ought to be rather less important than the lack of substance. Thunberg’s rhetoric has a tendency to lapse into demagogy—simplistic, emotive, accusatory, and apocalyptic. “You say you love your children above all else, and yet you are stealing their future in front of their very eyes,” she has sullenly instructed the assembled adults. And: “You are not mature enough to tell it like it is—even that burden you leave to us children.” The only “sensible” thing to do, she claims, is to “pull the emergency brake.”

What that would mean in practice? Thunberg is not detained by details. Culturico explains that she represents the “dark green” environmentalists, who blame a combination of overpopulation and technology for our changing environment. The “light green” view, on the other hand, is that overpopulation is not a problem per se, and that technology will be the answer to coping with climate change, not “pulling the emergency brake” by halting CO2 emissions. Thunberg admits that her preferred solution is not “politically possible,” but this has only convinced her of the need to “change the system.” Her ideas are emblematic of a radical environmentalism aligned with a far-Left anti-capitalism, and parts of her speeches could be mistaken for the recital of a revolutionary manifesto. “We have come here,” Thunberg proclaims, “to let you know that change is coming, whether you like it or not. The real power belongs to the people.”

Is this a message that children should be served without debate? In Edinburgh, the city council took the unusual step of endorsing the 15 March protest outside the Scottish Parliament, and encouraging children to take part. The council’s vice-convener for education Alison Dickie told the BBC that, “I am utterly proud of our young people. There can be no more powerful learning experience than getting actively involved in real life global issues, such as action on climate breakdown. I’m proud too that we are choosing to celebrate, rather than stifle, the positive energy of our young people, and it showcases the very caring and responsible citizens we are shaping across our schools.” Schools also supported the protests. But who are they to act as the moral arbiters of political issues? From here on out, can we expect councils and schools to take a position every time a march is organised?

Thunberg’s message is also profoundly cynical and pessimistic: “Our civilisation is being sacrificed for the opportunity of a very small number of people to continue making enormous amounts of money. It is the sufferings of the many which pay for the luxuries of the few,” she says. Today, Thunberg is a vegan and has renounced air travel. She claims to be independent, but in Katowice, where she spoke at the COPD24 conference, she informed her audience that she was speaking on behalf of Climate Justice Now!, a lobby group which describes itself as a “network of organisations and movements from across the globe committed to the fight for social, ecological, and gender justice.” The organisation believes that, since the northern hemisphere has caused emission levels to get too high in the first place, it should pay for the sins of the southern hemisphere. But in order to get emissions down, developing countries like India will have to get on board, or what developed countries do won’t matter all that much. Of the most polluting countries—US, India, China, Russia, Japan, and the EU nations—only India’s carbon emissions are rising (almost five percent in 2016) according to the Guardian. Although its emissions per person are miniscule, the size of India’s population means that its efforts to combat global warming will matter a great deal.

“Why should I be studying for a future that soon will be no more, when no one is doing anything to save that future?” Thunberg asks. This is a bleak and desperate view of the world, espoused by a girl fortunate enough to live comfortably (her mother is a famous opera singer) in one of its safest and richest countries. Not only is it melodramatic, but it is almost certainly counter-productive. Demands that people panic and warnings that the metaphorical house is on fire might make for effective rhetoric, but her counsel of despair is a strange way to inspire young people.

Thunberg says she has been diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome, an obsessive compulsive disorder, and selective mutism, and that she has suffered from depression and eating disorders that have stunted her growth. Although her fortitude in front of world leaders and the media’s cameras show that mental health issues need not stand in the way of becoming a highly visible public person, her mindset still seems to be mired in gloom. Mental health issues are reportedly on the rise among young people, with one in eight children aged between five and 19 receiving a diagnosis of one kind or another according to official UK figures. The appeal of someone like Thunberg may be symptomatic of a wider pessimism among the younger generation. One wonders if such a vulnerable young girl should be spearheading an international movement that attracts so much attention.

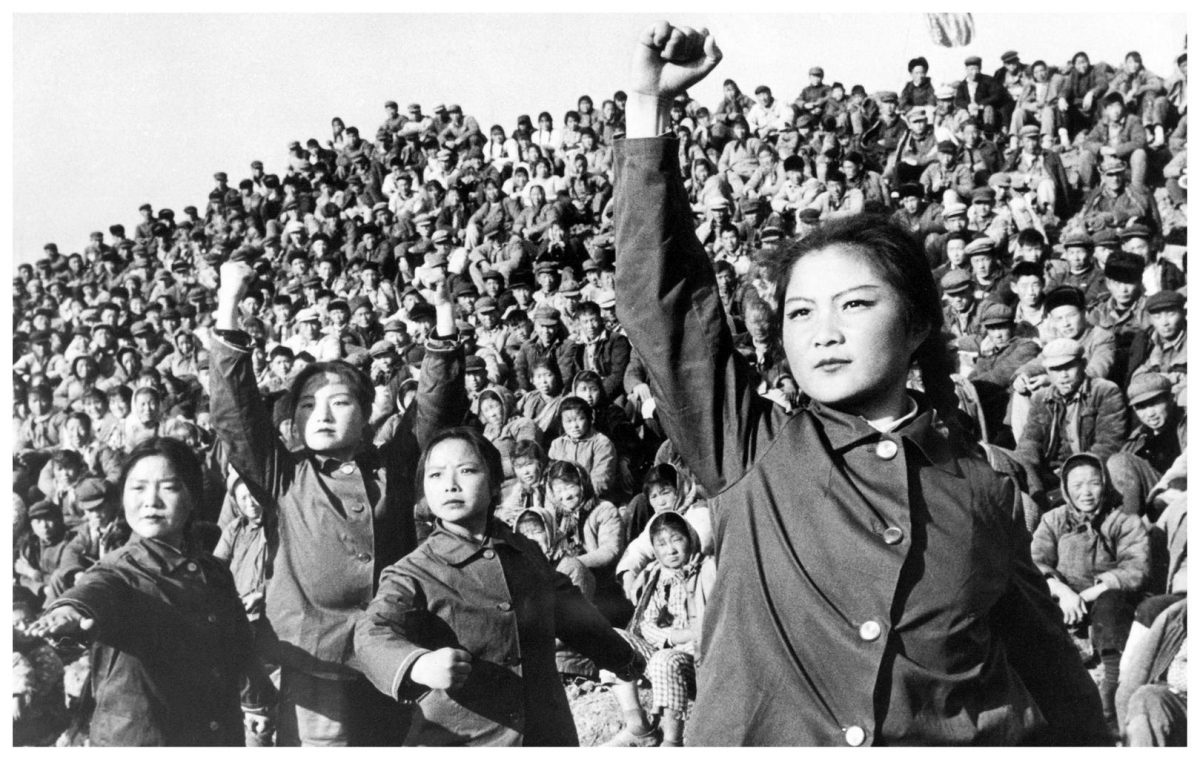

The protests in front of parliaments and city halls last Friday were largely peaceful, but in some cities the children were joined by organisations like Extinction Rebellion, which advocates direct action and in the past has closed streets and blocked bridges. In New York, 17 people from this group were arrested after a crowd of several thousand rallied on a bridge near Central Park. In London, police had to intervene after the young protesters brought the traffic outside parliament to a standstill. Some also climbed a statue of Sir Winston Churchill and hung placards on David Lloyd George, while others chanted obscenities about the prime minister and raised their fists in unison. UN secretary-general Antonio Guterres responded by praising the students: “My generation has failed to respond properly to the dramatic challenge of climate change,” he wrote on Friday. “No wonder they are angry.”

Historically, protests have met with mixed results—some like the Civil Rights Movement have changed whole societies, whereas others like the Occupy protests fizzled out having achieved very little (although protests can sometimes lead to longterm shifts in attitudes that are harder to measure). Perhaps the most reliable benefit of activism is the feeling of righteousness it offers its participants. “I don’t trust the activist ethos at all,” Jordan Peterson has remarked. “Everything about it is superficial and trendy and too easy, and it externalises the blame—the evil is always elsewhere.” The West, he went on, is based on the idea of the divine individual: “If we subsume that under group identity, then we will perish painfully.”

Bjorn Lomborg, author of Cool It and The Skeptical Environmentalist, tweeted: “Thunberg’s solution to ‘just say no’ is not only naive and impossible. Trying to attain it will incur tens or even hundreds of trillions of dollars of net costs.” Those costs would have a dramatic impact on the way of life these protesting schoolchildren presently take for granted. Lomborg argues that instead of ploughing more money into inefficient solar and wind power, more should be invested in innovating green energy to make it so cheap it eventually undercuts fossil fuels and halts climate change for good.

The climate debate is a complicated one. It requires the careful weighing of interests and trade-offs, not the uncompromising fanaticism of an absolutist. A sixteen-year-old should not be expected to see all the nuances, but as adults, we should expose her ideas for what they are: undemocratic, fatalistic, and bereft of the hope and optimism needed to effect consequential change. Thunberg’s speeches and Manichean worldview do not offer realistic answers to the problems we face. Even if her most alarming predictions turn out to be true, solutions will have to rely upon innovation and a realistic assessment of what is possible. Activism might be driven by passionate conviction and founded on good intentions, but as Saul Alinsky, the radical American writer and community organiser, once observed: “Young protagonists are one moment reminiscent of the idealistic early Christians, yet they also urge violence and cry, ‘Burn the system down!’ They have no illusions about the system, but plenty of illusions about the way to change our world.”