Anthropology

The Origins of Colourism

As revealed in the documentary, this view takes an emotional toll on dark women, who are discriminated against in all sorts of ways.

When Solange and Beyoncé Knowles’s father Mathew Knowles was asked in 2018 why he preferred to date women of a lighter skin tone, he replied, “I had been conditioned from childhood.” At least as far back as Gunnar Myrdal’s 1949 book An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy, social scientists have recognized discriminatory behaviour among African American males in favour of fairer skinned females, a bias that the 2011 documentary Dark Girls reveals is still unfortunately prevalent today. “I don’t really like dark skinned women, like, they’d look funny beside me,” disclosed one male interviewed for Dark Girls. “I’d like a pretty, light skin girl.”

As revealed in the documentary, this view takes an emotional toll on dark women, who are discriminated against in all sorts of ways. Darker skinned women in magazines and film often are airbrushed or photoshopped into a Beyoncé glow, and lighter skinned African American actresses and dancers seem to be cast disproportionately in film roles and music videos compared to some of their darker skinned colleagues. Even children absorb from others at an early age the notion that lighter skin is considered prettier than darker skin, and psychologists have shown an “attractiveness halo” effect whereby judgements on beauty spill over into judgements about other characteristics such as intelligence and moral worth, even to the point of influencing hiring decisions by employers. The specific process whereby members of one ethnic group discriminate against those within their own ethnic group based on skin colour has been labelled “colourism.” And with a little well-placed sad music and innocent facial shots, a doll experiment demonstrating its effects on children can extract a tear.

The overarching understanding of discrimination within African American communities is that such bias results from historical oppression. “In Western communities, it’s thought to be a lasting relic of slavery,” wrote Georgina Lawton in the Independent. In her 2018 article, Lawton decried the role played by the “global white supremacist capitalist patriarchy” in pushing an overwhelming “eurocentric beauty hegemony.” People of African ancestry, she argued, have been encouraged to value lighter skin because Western slavers treated darker and lighter slaves differently: Darker skinned slaves were subjected to harsh fieldwork, while lighter skinned slaves were afforded less burdensome housework instead. Or as another commentator put it, “It’s only favoured because of what Western society has taught us, and in our communities it’s perpetuated as banter.”

The Association of Black Psychologists has labeled colourism as a form of internalized racism, the process whereby ethnic minorities absorb the racism of dominant ethnic groups to their own detriment: “After hearing racist stereotypes and attitudes, a time comes when these are adopted as truth—internalized—and believed by those on the receiving end of the lie.” According to this view, the initial bias set in motion a cascade of oppressive policies and practices, such as segregated churches for light skinned and dark skinned people, which in turn promoted the association between light skin and higher status.

According to sociologist Aisha Phoenix, writing in Feminist Review, colourism has had consequences for ethnic groups around the world: “Many of those disadvantaged by colourism fail to see that the beauty hierarchy is an ‘arbitrary social construction’ that advantages fair, white women and multinational corporations, but has deleterious consequences for many who fail to meet its strictures.” By way of example, the World Health Organization reports that 77 percent of women in Nigeria use skin-whitening products (the highest rate of any country), some containing mercury that can cause lasting kidney damage. To Phoenix, this shows how corporations perpetuate racism to their own advantage: “The global politics of beauty promulgates an aesthetic and hierarchy born of ‘white supremacist thinking.’”

Despite the obvious political undertones, a lot of this theorizing seems eminently sensible to me. Indeed, it strikes me as highly intuitive that the disgraceful treatment of slaves and the imposition of coercive power structures along racial lines would have played a large role in forming enduring beauty perceptions among African Americans. But because of the nearly unanimous agreement that colourism is a product of Western hegemony, we’ve fallen into what John Stuart Mill called “the deep slumber of a decided opinion.” That slumber has led to an incomplete, low-resolution narrative perpetuated by journalists and academics alike in regard to colourism.

It’s notable that the issue of colourism in beauty norms has become a feminist issue in large part because of the sexually dimorphic nature of the phenomenon. As Lawton writes, “Colourism is a feminist issue because black men are allowed to be dark-skinned where women are not.” Which is to say that women in African American communities generally don’t perceive lighter skin in males to be any more desirable than darker skin—so that males can “get away” with being dark, even as they generally exhibit a preference for lighter skin in female mates. But this invites the question as to why slavery and oppression would arbitrarily lead to a male desire for female skin but have no corresponding effect on the opposite form of attraction. Clearly, some further explanation is needed.

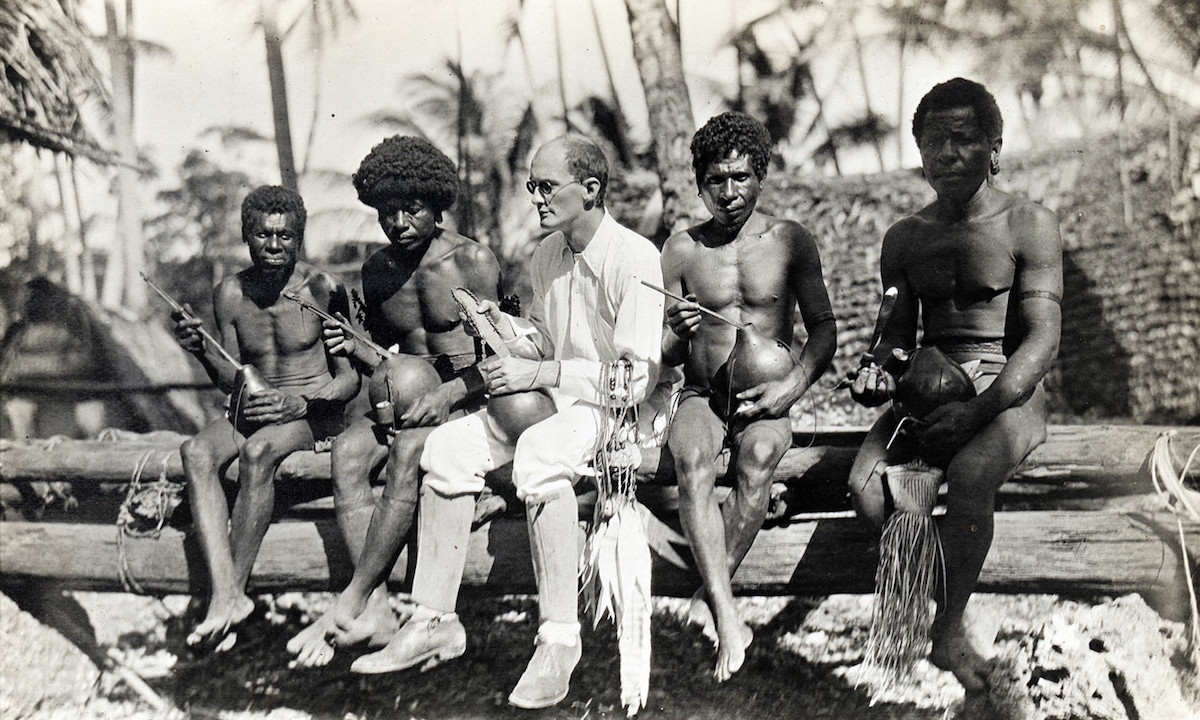

“As to the colour, dark brown is decidedly a disadvantage,” noted the renowned anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski in 1929, describing male desires for women in the Trobriand Islands off the east coast of New Guinea, “In the magic of washing and in other beauty formulae, a desirable skin is compared with white flowers, moonlight, and the morning star.” This description is specific to the Trobriand Islander’s own skin tones, and did not apply to white visitors, whose skin was perceived as too white. Ian Hogbin, similarly, wrote in The Island of Menstruating Men: Religion in Wogeo, New Guinea, the ideal skin tone was seen as “bright and clear as the petals of a flower,” but, “Europeans are most emphatically not envied for their blond coloring, which is regarded as far too reminiscent of albinos.” East of New Guinea in the Pacific Ocean lies the Solomon Islands, where Beatrice Blackwood wrote of the Buka in 1935, “In discussing with the men what physical attributes they considered desirable in their women, it emerged that they prefer a light skin, especially one with a reddish tinge, which is much less common than the darker brown.”

Leaving the Melanesian Pacific altogether and travelling northwest to Asia, we find a similar pattern. In Singapore, Cambodia and Thailand, billboards everywhere project images of light-skinned women smearing cream over their faces. Chinese people seem to be particularly judgemental on this subject; and for over a thousand years, the Geisha has been a symbolic focal point of perfection in beauty in Japan, her face smothered in white bird droppings or other whitening products. One Japanese scholar described the perfect skin tone as reflecting the “beautiful tuberculosis patient whose skin is pale and almost transparent.” The wealthiest Japanese men often are said to marry the lightest skinned females, paralleling sub-continental practises in India and Bangladesh.

Ancient Aztec codices in Central America revealed the use of cosmetics by women to attain a lighter skin, and paintings from ancient Egypt depicted women with lighter skin than males. In the Arab world, more broadly, one early traveller noted, “The highest praise is perhaps ‘She is white as snow.’” In North America, one Hopi chief commented, “We say that a woman with a dark skin may be half man.”

In subsaharan Africa, it’s much the same. Writing in 1910, Moritz Merker stated of the most sought after Masai women of Kenya and Tanzania, “Further requirements for being regarded as beautiful are an oval face, white teeth, black gums, a skin color as light as possible.” John Barnes wrote in 1951 of Ngoni in Malawi, “Young men say that what they like in a girl is a light skin colour, a pretty face, and the ability to dance and to copulate well.” Of the inhabitants of the Kalahari Desert in Botswana, among the most isolated people in Africa, another anthropologist wrote, “the generally admired type is a light-skinned girl of somewhat heavy build, with prominent breasts and large, firm buttocks.” Speaking of the strategic posturing of jealous women in Zambia, C.M.M. White recorded that, “dark-skinned women conscious of their possible disadvantage have been heard to tell men that light-skinned women will be found to be sexually unsatisfying.”

This pattern amounts to more than mere anecdote. In a 1986 report published in the journal Ethnic and Racial Studies, anthropologists Pierre van den Berghe and Peter Frost dusted off some understudied ethnographic archives contained in the Yale-based Human Relations Area Files, and found that in the great majority of societies for which there is data, lighter skinned females do in fact feature as the beauty ideal, whereas no clear pattern emerges for female’s preferences for male skin tone.

There were only three societies identified by the anthropologists that reportedly didn’t subject female beauty to a colourist evaluation, but in each of these cases the evidence was ambiguous as to beauty norms. Even counting these three cases as negative findings, van den Berghe and Frost concluded that there is an overwhelming cross-cultural pattern of colourism in male sexual desires that places lighter skin females above darker members of their community. They also argued that Western contact couldn’t possibly explain the phenomenon due to its ubiquity throughout the historical records of Egyptians, Indians, Chinese, Japanese and Aztecs, and in societies not colonized by the West or with limited contact. Van den Berghe and Frost calculate the probability of their data set arising by chance to be “less than one in 100 million.”

The two researchers also found that lighter-skinned women are not only preferred in almost every society, they also have lighter skin compared to men in most societies, and this anomaly could not be explained by sun exposure—which suggests that some force in evolutionary history has selected for lighter women.

In particular, Van den Berghe and Frost found that women tend to have the lightest tone of skin during early adulthood, during the most fertile period of her menstrual cycle, and when they are not pregnant—in other words, when a woman is most likely to conceive: “There appears, in short, to be a linkage not only between pigmentation and sex, but between light pigmentation and fecundability in women.”

They hypothesized, firstly, that the correlation between lighter skin complexion and fertility led to a genetically programmed learning bias in males, which usually manifests as a cultural preference for lighter skinned females. But once this colourist discrimination took place on the cultural level, they further hypothesized, sexual selection caused the further lightning of female skin pigmentation, explaining the lighter pigmentation we now find in females as compared with males.

This theory of gene-culture coevolution is not without its critics. And contradictory findings exist as to the difference in male-versus-female skin tones and the linkage between menstruation and skin tones. But what seems to be firmly established is that the cross-cultural bias for lighter skin does in fact exist and that it arises for reasons independent of oppressive forces exerted by the West. The question then becomes to what degree oppressive historical forces have further intensified a colourism toward women that already existed.

This is not an easy empirical question to answer, because hardly any longitudinal ethnographic studies exist on the extent of colourism in these communities before and after contact with the white world. One rare example does exist, however, in the form of a 1954 study produced by anthropologist Edwin Ardener, in regard to the Ibo of eastern Nigeria. Ardener noted that, “In Ibo culture…yellowish or reddish complexions are considered more beautiful than the darker, ‘blacker’ complexions,” and reproduced the statement of one Ibo man: “Well, you know that a thing that is ugly is first of all really black…You don’t want people to laugh at you and say, ‘Is that your wife?’”

This bias for lighter skin in women, Ardener noted, led to real consequences for darker women, for they extracted a lower bride price than their lighter-skinned counterparts, and were afforded less prestigious marriage ceremonies. According to Ardener, these beauty standards were reportedly part of established ritual and religion among the Ibo before the era of Western influence: “The Ibo evidence suggests that preference for paleness of complexion is indigenous.”

However, Ardener notes that while those with pale complexions have traditionally been seen as the most beautiful women among the Ibo, and that “divergence never occurs on this issue,” a general cultural belief had it that darker skin women could work much harder in the sunlight than lighter-skinned women, providing a trade-off between the beauty and the work capability of a woman.

And this is where things get sociologically interesting: In a society living close to subsistence levels, there obviously is much value in marrying a woman who is seen as more likely to help her family survive hardship. But upon the establishment of European colonially administered towns and economic patterns, women increasingly were afforded the opportunity to work indoors—and, in some cases, had the opportunity to avoid work altogether. This meant that the perceived economic value of darker skin fell. As a result, a further shift toward valuing lighter skinned women was observed in such towns, as well as increased use of cosmetics in an escalating race towards lightness. (The sight of European women in these towns, whom the Ibo regarded as having “the most beautiful ocha complexion,” likely further compounded the problem.)

Through this glimpse into Ibo culture, we can see how the ex ante exaltation of lighter skin in females and the practice of colourism were further strengthened not only by the diffusion of Western culture, but by the changing socio-economic structure of society under colonialism. And yet, absent pre-existing biases, the post-colonial outcome might have been different. Van den Berghe and Frost point out, for example, that the conquest of parts of western Europe in the 8th Century by Muslim Africans did not shift beauty perceptions among Europeans toward the darker skin of their rulers—in part because there was no pre-existent bias at play.

Drawing out the implications of these anthropological insights is not an easy task. And we must heed the famous paraphrase of H.L. Mencken that, “for every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple and wrong.” Exhibit A: Margaret Hunter’s 2005 book Race, Gender and the Politics of Skin Tone, in which it is claimed that, “without a larger system of institutional racism, colourism based on skin tone would not exist.” The historical evidence suggests that this claim is simply untrue.

Another issue that confounds this discussion is the failure of observers to distinguish between historical socio-cultural forces such as slavery, and current norms of beauty and values in our society. While Lawton decries the West as a “society obsessed with fair skin,” ours is in fact the only society we know of where most people unambiguously prefer a skin tone darker than the average tone of its ethnic plurality. We Westerners burn ourselves into an early carcinogenic death by tanning in the sun or solariums, or by spending billions of dollars on tanning oils and fake tans to achieve bronzed skin.

One 2006 survey of Westerners concluded that brown skin is considered more beautiful than fair skin. Another survey, this one from 2014, found that French men prefer a darker skin than what Africans from Mozambique considered to be attractive. The West has moved on from the Victorian practice of shielding oneself with an umbrella in the sun, even if those seeking to blame colourism on Western bigotry haven’t noticed.

“Shaming dark skin is a foundational tenet of many beauty norms,” wrote one blogger in 2016, puzzled by the appearance of “chocolate”-themed spray-can tanning products. “So it is quite bizarre to see dark skin being bottled up and sold like this.” But such products should not come as a surprise. As one dark-skinned African American woman revealed in the Dark Girls documentary, “there are places I’ve gone where there are a lot of whites and they would tell me, ‘You have such beautiful skin’…and it’s really questionable to me, why is it that they think I’m so beautiful and my own people don’t see any beauty in me at all.”

I recall reading, only a few years ago, a satirical piece that pretended to argue that skin tanning is a form of “cultural appropriation.” Well, social justice activists have caught up with the satirists by unironically embracing this very position. Indeed, Vrinda Jagota, associate editor of the New York-based magazine Paper, has suggested that white people should check their privilege before stepping out into the sun:

It’s that time of year again—the sun has finally reemerged and people are spending their Saturday afternoons lounging on crumpled blankets drinking La Croix in Prospect Park … I’ve always been intrigued and slightly annoyed by white people’s obsession with tanning. When they compare their skin tone to mine, it feels like appropriation, a co-option of brownness without ever having to deal with the oppression people of color face for their skin color … I’m sure the well-meaning white reader is wondering what they are supposed to do. Not go into the sun this summer? Wear SPF 90 at all times? Sadly, the answer is not so obvious or so easy.

“Racism rears its ugly head again,” wrote Simone Mitchell for an Australian news outlet. In reprimanding the spray-tan industry for cultural insensitivity, she likened the products to blackface. Denouncing the names of a Swedish company’s spray-tan products—such as Dark Ash Black and Dark Chocolate—Teen Vogue declared flatly: “The names and the shades = not OK.” Indeed, the products were likened to a violent hate crime by one commenter, who wrote: “It reminds me of the typical scary movie where the murderer kills the person, cuts off their face, and wears it as a mask.”

So is it racist to abhor dark skin—or is it racist to celebrate it? They’re both objectionable, apparently. In 2017, the Daily Mail profiled activists who warned that little girls shouldn’t dress up as the Polynesian character Moana because that would be “racist cultural appropriation”—while also discouraging dress-up as Elsa from Frozen because such costumes would promote the paradigm of “white beauty.” The example perfectly mirrors the damned-if-we-do/damned-if-we-don’t debate about colourism.

Argument about racism and the allegedly white supremacist nature of our society would find greater support if there were more coherence to the pattern of evidence brought to bear. If we are being made to believe that the celebration of white and dark skin types are both evidence of racism, then one might properly conclude that there is little validity to either claim.

Lost amidst the overflowing storm of contradictory grievances and the sweeping tide of politically motivated commentary, meanwhile, is a nuanced conversation about the actual origins of colourism. Such a discussion might help make people appreciate that the admiration for many different skin hues observed in modern Western societies is actually an unusual but thoroughly welcome development.