recent

It Isn’t Your Imagination: Twitter Treats Conservatives More Harshly Than Liberals

Harassment and the advocacy of violence are serious issues, and there is nothing morally objectionable about social media companies.

This is a response to “Who Controls the Platform?“—a multi-part Quillette series authored by social-media insiders. Submissions related to this series may be directed to [email protected].

Many conservatives believe that social media companies are biased against their views. This includes Donald Trump, who last year accused Twitter of “shadow banning” Republicans, and promised to “look into this discriminatory and illegal practice.” A few months later, Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey made a categorical denial of any bias while testifying before Congress:

Let me be clear about one important and foundational fact: Twitter does not use political ideology to make any decisions, whether related to ranking content on our service or how we enforce our rules. We believe strongly in being impartial, and we strive to enforce our rules impartially.

Recently, Mr. Dorsey appeared on two different podcasts, on which he similarly denied any bias against the right.

Not everyone is convinced. A June, 2018 Pew poll found that 72% of Americans believe that social media companies censor views they don’t like, with members of the public being four times more likely to report a belief that such institutions favor liberals over conservatives than the opposite. Podcasters Joe Rogan and Sam Harris both received backlash from their respective audiences for not pressing Dorsey hard enough on the censorship issue.

Until now, conservatives have had to rely on anecdotes to make their case. To see whether there is an empirical basis for such claims, I decided to look into the issue of Twitter bias by putting together a database of prominent, politically active users who are known to have been temporarily or permanently suspended from the platform. My results make it difficult to take claims of political neutrality seriously. Of 22 prominent, politically active individuals who are known to have been suspended since 2005 and who expressed a preference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, 21 supported Donald Trump.

I began my analysis by compiling a list of every prominent individual or political party known to have been banned from Twitter since its founding. As a proxy for prominence, I used the criterion of whether the ban was important enough to warrant coverage in mainstream news sources. With the help of two research assistants, I searched both conservative and liberal media sources.

It is possible that I missed certain cases. In order to ensure reproducibility, I have made the data on suspended individuals and groups available online. And I invite readers to contact me if I missed any cases or made any errors. But given the wide variety of sources we used to compile the database, it is unlikely that any oversights would be substantial enough to meaningfully change the results.

I included only those cases in which the identity of the banned individual or entity was clear. Sometimes, Twitter removes an account because a user is thought to be engaging in a program of disinformation—for example, accounts allegedly run by agents of the Russian government that purport to identify with one side of the American political spectrum. To exclude such spurious cases, I designed my own database to include only unambiguous cases of identifiable individuals or organizations from English-speaking western democracies believed to be engaging in political advocacy in good faith. I counted individuals who are primarily known for their political activism, such as Milo Yiannopoulos; and others who are famous for other reasons but who also regularly comment on politics, such as the actor James Woods. As my main interest is political bias within the U.S. political spectrum, I also excluded terrorists and other Islamic extremists such as ISIS supporters.

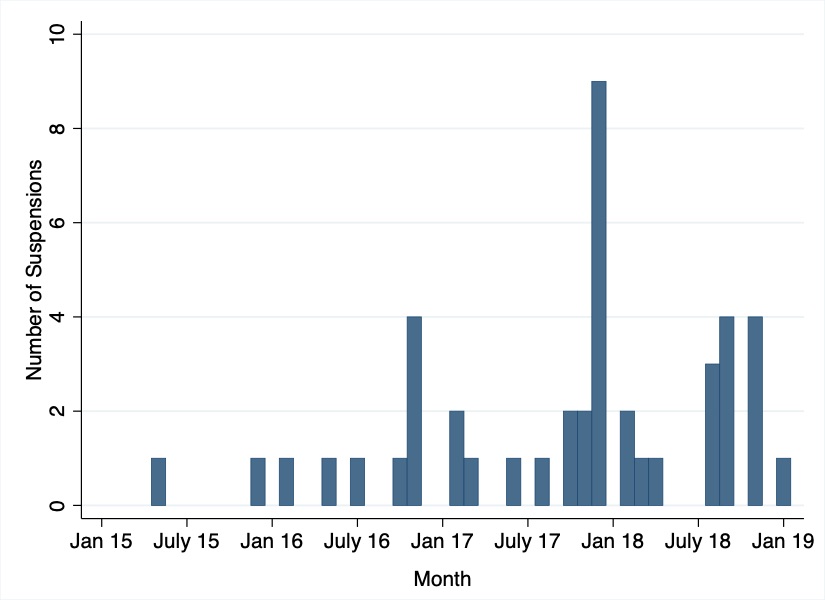

Twitter debuted in 2006. Yet I could not find a case of the company suspending or banning a prominent person before May 2015. While this may be due to deficiencies in reporting, it also may reflect Twitter’s claim at the time that it was “the free speech wing of the free speech party.” The following chart shows the number of monthly suspensions from 2015 to January, 2019.

I found it difficult to establish the extent to which any of the suspended individuals or groups clearly supported Republicans over Democrats or vice versa. Classifying them along the left-right axis is also problematic, as there are some figures that neither side would be eager to claim. Most prominent individuals who were suspended did express a preference in the 2016 election, however. And by restricting our analysis to this subset, and counting how many supported Donald Trump or Hillary Clinton, we can create a rough measure of whether there is bias, albeit one with a small sample size.

As noted above, of the 22 suspended individuals, only one was a Clinton supporter. This was actress-turned-activist Rose McGowan, who temporarily lost access to her account in 2017 for posting someone’s private phone number. Note that this is an unambiguous violation of Twitter’s rules, so the platform had little choice in this case. The platform does not seem to have suspended a single prominent Clinton supporter based on the substantive content of his or her expressed views.

Of course, the existence of this disparity does not prove that Twitter is actively discriminating against Trump supporters. Perhaps conservatives are simply more likely to violate neutral rules regarding harassment and hate speech. In such case, the observed data would not serve to impugn Twitter, but rather conservatives themselves.

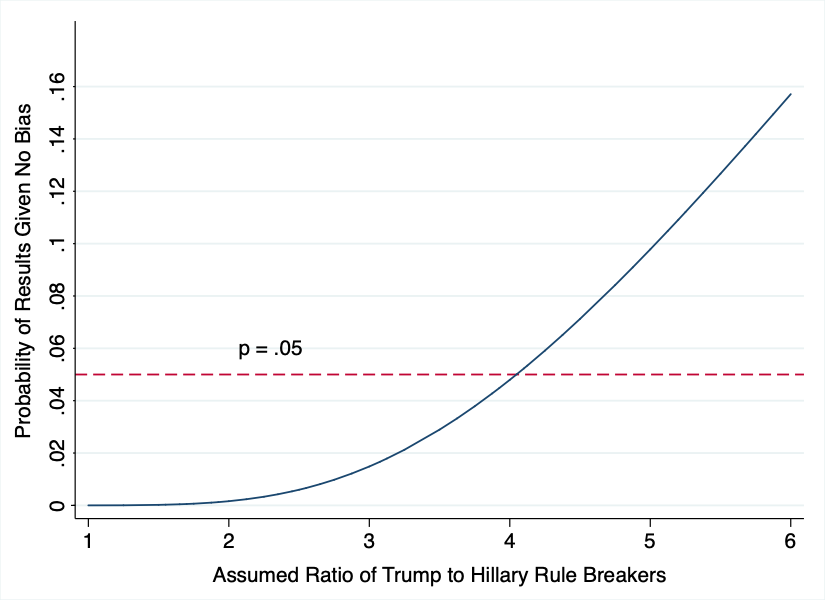

Luckily, through the use of standard statistical methods—similar to those commonly applied to calculate confidence intervals in the physical and social sciences—one may determine that the underlying population disparity (i.e. the disparity between liberal and conservative behavioral norms) would have to be quite large in order for there to be any significant likelihood of observing a randomly constituted 22-point data set characterized by the above-described 21:1 ratio. Indeed, assuming some randomness in enforcement unrelated to bias, one would have to assume that conservatives were at least four times as likely as liberals to violate Twitter’s neutrally applied terms of service to produce even a 5% chance (the standard benchmark) that a 22-data point sample would yield a result as skewed as 21-1.

Are prominent Trump supporters more likely to break neutrally applied social media terms of service agreements than other voters? Perhaps. But are they four or more times as likely? That doesn’t seem credible.

Indeed, it is not difficult to find cases of liberals engaging in speech that appears to cross the line while not being punished for their transgressions. This includes the case of Sarah Jeong. After she was hired as an editorial writer for The New York Times, it was discovered that over the years she had posted dozens of messages expressing hatred and contempt of whites. When conservative activist Candace Owens copied some of Jeong’s tweets and replaced the word “white” with “Jewish,” she was suspended from the platform. Perhaps realizing how hypocritical this looked after they had not taken any action against Jeong, Twitter allowed Owens back on, but only after she deleted the offending tweets.

Interestingly, if you search “Sarah Jeong” in Google, you get no auto-complete suggestions regarding her controversial tweets, despite this being the source of considerable infamy. On Bing and Yahoo!, “Sarah Jeong racist” is the first offered search suggestion when her name is typed in. While one could argue that individuals’ worst moments shouldn’t follow them around forever, it is difficult to imagine a big tech company suppressing unflattering information about a conservative in a similar manner.

Another particularly shocking case is that of Kathy Griffin, who demanded that her followers make public the names of the Covington High School students who were falsely accused of aggressively harassing a Native American activist. Despite this explicit call to harass minors, she has not been sanctioned by Twitter.

Left-wing activists on college campus regularly engage in the practice of de-platforming—including the use of violence or the threat thereof as a means to prevent someone from speaking. Victims of this practice typically are conservative figures such as Ben Shapiro and Ann Coulter. At Berkley, when Milo Yiannopoulos tried to give a speech, a large mob threw stones and fireworks at police officers, and attacked members of the crowd. Around the same time, commentators noted that during the 2016 president campaign, when Bernie Sanders visited Liberty University, the evangelical institution run be Jerry Falwell, Jr., his message was met with “polite skepticism.”

Are we to believe that while prominent figures on the left encourage uncivil and even violent tactics, both on and off college campuses, their online behaviour is, with the solitary exception of Rose McGowan, universally exemplary?

Harassment and the advocacy of violence are serious issues, and there is nothing morally objectionable about social media companies removing this kind of content from their platforms. However, such laudable objectives should not be used as cover to prosecute ideological campaigns. While social media platforms are private companies, anti-discrimination laws generally allow legislators avenues to address businesses that exhibit unacceptable biases in how they treat the public.

It is unthinkable that we would allow a telephone or electricity company to prevent those on one side of the political aisle from using its services. Why would we allow social media companies to do the same?