Art and Culture

Tiers of Pride and Shame

Pride and shame are two sides of the same coin; so if collective pride makes sense, then collective shame makes sense too

On December 9, in the small hours of the morning, a drunk Columbia undergraduate student named Julian von Abele was filmed outside the campus’s main library delivering a passionate ode to whiteness. “White people are the best thing that ever happened to the world,” von Abele declared to a group of students, many of whom were not white. “We invented science and industry, and you want to tell us to stop because, ‘Oh my God we’re so bad.’” In an ill-fated attempt to pacify the collection of students surrounding him, he added the caveat, “I don’t hate other people, I just love white men.”

Students and administrators reacted to the incident with unanimous condemnation. Barnard College, Columbia’s sister school, banned von Abele from campus. Many argued that von Abele’s tirade should be understood not as an isolated event, but as a symptom of the university’s ongoing complicity in white supremacy—a systemic problem calling for a systemic solution. Columbia’s Black Student Organization led the charge with a list of demands including extra time for affected students to complete their final exams; increased funding for minority faculty recruitment, on which the university has already spent $185 million since 2005 to little apparent effect; and an unfortunately phrased call for “the incorporation of scientific racism into the Frontiers of Science syllabus.” (Surely they meant the incorporation of information about scientific racism.)

But an isolated event doesn’t indicate a systemic problem. Like so many things nowadays, extrapolating from a single event to a crisis is only wrong when your opponents do it. Just a few months ago, many commentators on the Right extrapolated a supposed crisis of illegal immigrant crime from the murder of a single American by an illegal immigrant. At the time, progressives recognized this for the irrational fear-mongering that it was. Yet it is the same flawed logic that extrapolates an alleged crisis of campus racism from a single racist incident.

Besides, there remains the question (nearly unaskable in polite company) of whether von Abele’s drunken diatribe was actually racist to begin with. Sure it was narcissistic, self-pitying, and belligerent. But was it an expression of bigotry?

At a glance, it’s hard to reconcile the belief that von Abele’s comments were bigoted with the fact that black activists routinely get praised for making similar statements. Von Abele’s remark, “I love myself and I love white people” sounds eerily similar to “I love my blackness and yours,” the Twitter mantra of Black Lives Matter leader Deray McKesson. “We’re white men, we did everything,” nearly echoes a statement made in a commencement speech by Alicia Garza, a co-founder of Black Lives Matter: “Without black women…there would be no me, no you, no us, no civilized society of which we speak. We—I, you, and me—we owe everything to black women.” Von Abele’s monologue, universally condemned, took lines straight from the scripts of America’s most celebrated racial justice advocates.

On the prejudice-plus-power conception of racism, von Abele’s position in the racial privilege hierarchy as a white person renders his comments racist, whereas McKesson and Garza’s positions as members of a historically marginalized group renders theirs permissible, if not enlightened.

A great way to instantly be seen as a naïf, a racist, or both is to ask why this double standard exists. The answer, of course, is historical context. Black people were brought to America in chains, forced to work as chattel, subjugated formally and informally for a century after abolition, all the while fighting to see themselves as beautiful in a culture hellbent on convincing them they were ugly, stupid, and inferior. Black race pride, therefore, is a rejection of, and an adaptation to, the racist elements in America’s reprehensible past. One cannot make the same claim about white race pride, which historically has been more associated with brutal oppression than with noble rebellion.

This history lesson is without doubt important. But does the fact of anti-black racism, whether past or present, overt or systemic, prove that it’s okay for a white person to be banned from a campus for saying things that black people get ovations for? Decent, ethical people are supposed to vigorously nod “yes”—or better yet, not ask the question at all.

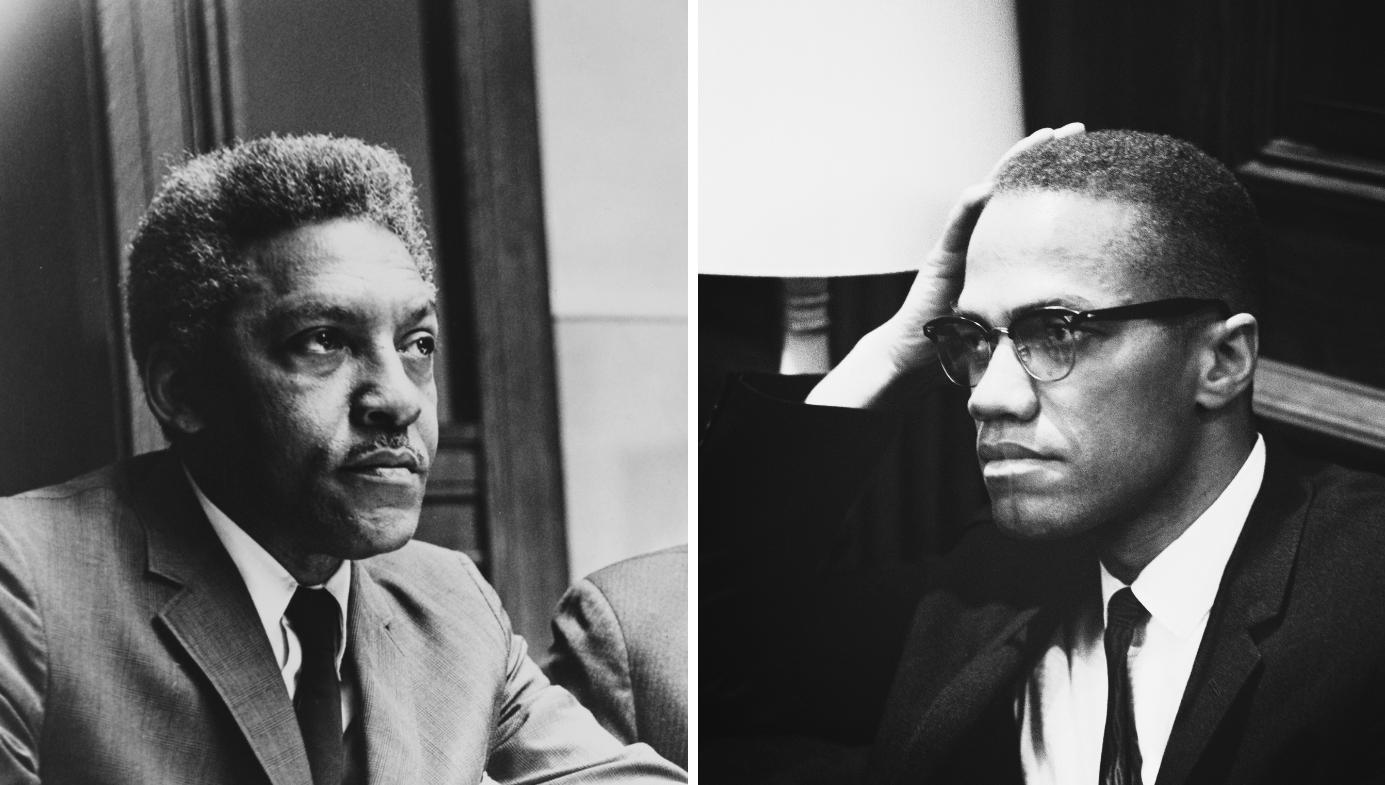

Yet the view that black people cannot be racist would have been alien to the civil rights leaders and activists of yesteryear, who experienced far more anti-black racism than the leaders of Black Lives Matter do today. Bayard Rustin, Martin Luther King Jr.’s strategist and the chief organizer of the March On Washington, was arrested no less than 23 times during an era of profound racism. He nevertheless considered it obvious that blacks could be racist just like whites, and he vocally opposed such racism wherever he encountered it.1 The same is true of Eldridge Cleaver, an early leader of the Black Panther party.2

But, more to the point, if we decide to give black activists a free pass to express racial pride because they face racial slights, why not allow von Abele the same pass? After all, Columbia’s campus is no stranger to anti-white rhetoric. Take, for instance, the criticism, commonly heard in Columbia dorm rooms, that the Western canon is deficient because it’s filled with “dead, white men.” Does having to hear the likes of Homer, Plato, and Rousseau dismissed not as bad writers, but as writers of your race, qualify you to express race pride in response?

And the “dead, white, men” trope is only the tip of the iceberg. In my two and a half years on Columbia’s campus, I can count my experiences of anti-black racism on one hand—indeed, one finger. By comparison, I could fill a small diary with the anti-white comments (some intended in jest and others in earnest) that I’ve heard.

I sometimes wonder how I would feel if I had to hear Frederick Douglass, Bayard Rustin, and James Baldwin dismissed in casual conversation not as bad writers but as “dead, black men.” I wonder whether I would have the presence of mind to dismiss such statements as harmless nonsense, or whether the experience of hearing my heroes derided in explicitly racial terms—terms that linked their inadequacy to my own racial identity—wouldn’t awaken a sense of grievance within me. I wonder, moreover, how I would feel if I couldn’t complain.

Von Abele’s error was not that he expressed white racial pride. His error—along with McKesson’s and Garza’s—was to play the racial pride game at all. The notion that your value lies in your membership to the race you were born into by chance makes no sense; taking credit for the achievements of other people with whom you share a skin color makes no sense. Rustin put it well when he observed that “the breast-beating white makes the same error as the Negro who swears that ‘black is beautiful.’ Both are seeking refuge in psychological solutions to social questions.”3

What’s more, pride and shame are two sides of the same coin; so if collective pride makes sense, then collective shame makes sense too. The same flawed logic that allows von Abele to feel proud of the accomplishments of dead, white men should lead him to feel ashamed of their sins. Conversely, the progressive logic that encourages modern-day whites to feel shame for slavery and colonialism should also lead them to feel pride for their ancestors’ achievements. Both white chauvinists and white progressives dogmatically reject one half of the pride-shame binary. Both factions should go one step further and reject the concepts of collective pride and collective shame altogether.

The massive gulf between how we treat expressions of white pride and black pride is unsustainable. I don’t expect the gulf to collapse into a colorblind singularity overnight; that would be unrealistic. But anyone who values consistency and believes that a person’s skin color is irrelevant to their moral character should want, at a minimum, to begin narrowing the gulf.

References:

1 See Bayard Rustin, “From Protest to Politics” (1964), “The Mind of the Black Militant” (1967), “Civil Rights and Uncivil Wrongs” (1982), and “The Curious Case of Louis Farrakhan” (1987).

2 See Eldridge Cleaver on Malcolm X in Soul On Ice, p. 106, and see Cleaver on Louis Farrakhan: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/race/interviews/ecleaver.html

3 Bayard Rustin, “The Failure of Black Separatism” (1970).