Top Stories

On the Value of Truth

Very few of us can actually deal with too much truth, so we rarely enquire too deeply into the justifications for our beliefs.

Many claim that we live in a “post-truth” era. Trust in major civic and political institutions is rapidly declining. People on all sides of the political spectrum dismiss the media as biased at best and little more than “fake news” at worst. The postmodern President of the United States is the most powerful man in the world, and according to Politifact makes statements that range from “half true” to outright lies 83 per cent of the time. In an earlier article for Canada’s The Hill Times, I invoked the philosopher Harry Frankfurt and summarized these developments as a rising “Age of Bullshit.” Concurrently, our post-truth era has been marked with lamentations across the ideological spectrum by those who provide a variety of explanations for our climate of untruth. Many progressives and liberals pin the blame on manipulative conservative politicians such as Trump and Boris Johnson, interference by foreign governments and cyber-attacks, and politically biased media. Many conservatives, meanwhile, pin the blame on progressive activists, the rise of PC culture and oversensitivity, and…politically biased media. I have already offered my own opinions on the roots of the “Age of Bullshit,” characterizing it as a natural development of postmodern culture, so I will not repeat my position here.

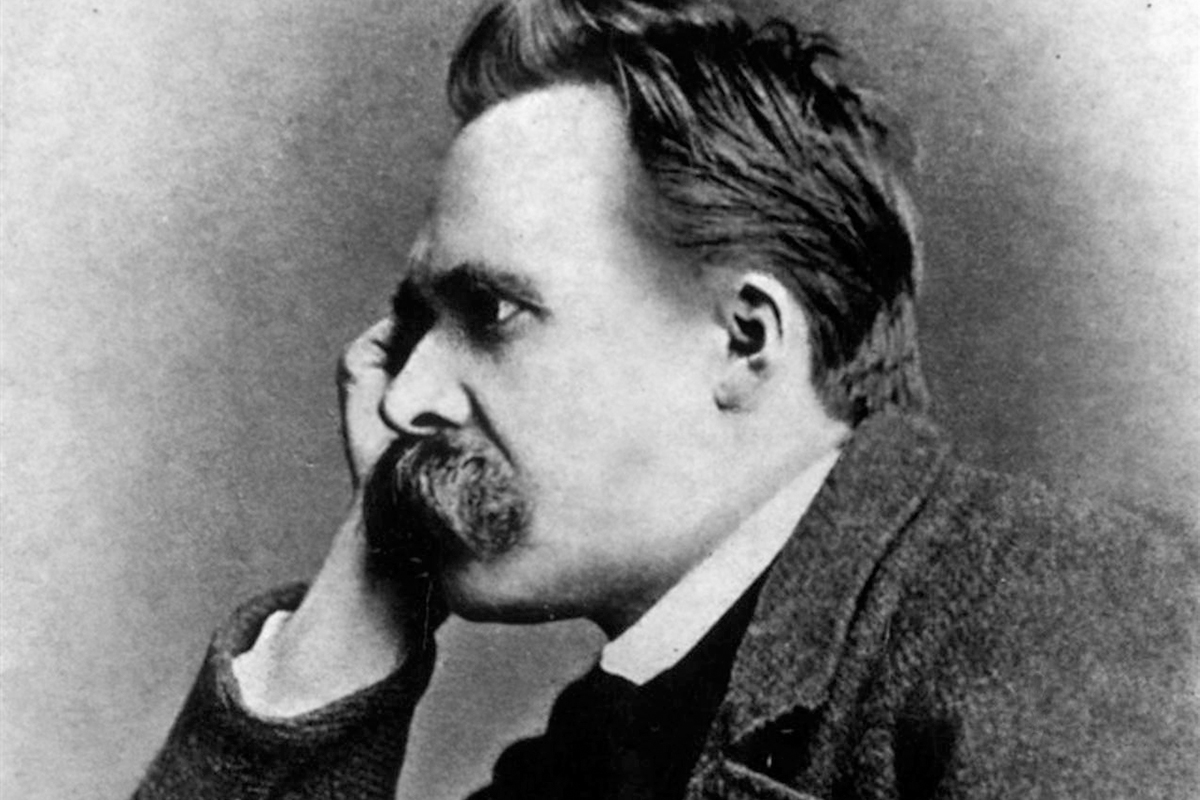

In this short article, I want to analyze a somewhat different question: Why do we value the truth at all? This was a major theme in Bernard Williams’ seminal 2004 book Truth and Truthfullness: An Essay in Genealogy. Inspired by the work of Nietzsche, especially his essay “On Truth and Falsity in a Nonmoral Sense” and On the Genealogy of Morality, Williams asks a different set of questions to those normally seen in standard philosophy. Most philosophers ask questions like “What is truth?” or “How can we discover truth?” These are obviously important questions and no right-minded person would be indifferent to them. But what Williams (following Nietzsche) is interested in is the “virtue” of truth; what roles does truth play in our lives, and is it valuable? How much truth are people really capable of handling? Are there circumstances where untruth might actually be valuable or even expected? These are peculiar questions, but asking them can help us get a better grip on why truth is virtuous, and why our post-truth era suffers from so many defects.

The Value of Truth

Truth has long been highly valued in Western thinking; indeed, at various points it has been considered the paramount value of human thinking and life generally. Plato famously characterized truth as something eternally beautiful for which the human soul most yearns. This characterization was influential in guiding the Christian conception of God, who was often conceived as an eternal figure who linked truth, beauty, and goodness into a complete whole. Immanuel Kant argued that telling the truth was a categorical moral duty which could not be contravened, even when doing so might lead to better consequences for individuals overall. And Einstein echoed Plato’s arguments when he quipped that “Politics is for the moment, an equation is forever”; rejecting the subjective to-and-fro of the political sphere for the eternal truth of physics and mathematics.

The reason truth was valued so highly by these figures is that they related it to some prized conception of rationality, whether that rationality were applied to our understanding of the world, or to one’s moral obligations. Truth was considered valuable because it enables us to see the world as it is without prejudice or bias, and moreover (according to some, most importantly) it enables us to act according to true moral dictums. Of course, what the world truly “is” and what constitutes true moral dictums has always been the subject of furious debate and controversy. Plato’s conception of truth and goodness is obviously very different than Kant’s, and in turn the thinking of both men seemed highly abstract and unempirical to someone like Karl Popper. But whatever conception they adopted, all these figures agreed that truth was important because it gave us a better sense of reality and our duties within it. Looking at the matter more personally, many also valued truth because it seems to have an integral relationship to selfhood and authenticity. An individual who is truthful, both with others and with one’s self, is someone who presents who they truly are without distortion or with the aim of manipulating others. Expressing the truth to others and to oneself enabled individuals to become persons characterized by integrity; someone like Atticus Finch in Harper Lee’s novel, To Kill A Mockingbird.

Alongside these high evaluations of truth have come many damning accounts of why so many people are unwilling to be truthful. If truth is so valuable, as the aforementioned authors suggest, why are so many people untruthful? Early figures tended to give highly personalized answers. Plato followed Socrates in condemning many people for mindlessly adhering to doxa (loosely translated as public opinion); they accepted the opinions of the many because that was easier, without bothering to look too deeply into their truth or falsity. Kant agreed, arguing that many people are far too willing to let themselves be influenced by heteronomy—outside influence—because it is more difficult to use reason and think for themselves. In the post-Romantic era, we are more prone to giving more social explanations for the persistence of untruth. Many on the political Left claim a system of ideology, or hegemonic discourses etc, manipulate people into adopting positions and opinions which are both untrue and not consistent with their actual self-interest. On the political Right, pundits complain about citizens being “indoctrinated” by leftist academics and activists, who use shame to constrain and silence their opponents, often putting “feelings” before “facts.” Most dramatically, Hannah Arendt wrote vividly about the emergence of totalitarian societies so fundamentally dedicated to propagandizing untruth that their leaders “never [compare] the lies with reality.” Each of these positions laments that many people are unwilling or unable to access the truth, whether due to personal vice and laziness or some form of social manipulation. The implication is that a better society than ours would be one in which far more people were willing to be truthful.

This extraordinary value placed on truth—whether because it is good to be rational, or important to be authentic—pervades the Western tradition and has certainly trickled down to our everyday discourses. For instance, truth denying and/or dishonest people pervade our literature and pop culture. Perhaps the archetypal villains of Western literature are Shakespeare’s Iago and Milton’s Satan; both master manipulators happy to spin lies and dishonesty to achieve their nefarious ends. The influence of these archetypal characters is seen in figures like Littlefinger and Cersei from Game of Thrones, or Emperor Palpatine in George Lucas’s Star Wars saga. More realistically, there are a surfeit of lying politicians portrayed in fiction; from Macbeth to Voldemort and Frank Underwood. These figures reflect our vivid awareness that our leaders often are less than candid with us. Then there are other figures who also deny truth, but not just to others, but to themselves. Literature and pop culture are filled with portrayals of ideologues, fanatics, and the delusional; all individuals who consciously or unconsciously ignore the truth about the world or themselves in pursuit of their goals. These range from mundane but tragic figures like Leo Tolstoy’s pitiful Ivan Illyich, continuously trying to deny the truth of his own mortality, to monsters like Heath Ledger’s Joker, unwilling to admit or recognize the truth of his own origins. These figures vary in how they distort the truth. But their notoriety as pitiful or villainous characters demonstrates the tremendous cultural value we continue to place on truth; an inheritance from a long tradition. This perhaps explains the furor now emerging about our transition to a post-truth era.

The Deficiencies of Truth

I suspect that the discussion of truth’s value given above will be familiar to many. Indeed, as I mentioned, the value of truth is so often taken as self-evident that we are unlikely to question it. Less often discussed are the many ways in which the persistence of untruth has often been accepted and even praised by many figures. This belies a deeper problem gestured to above: if we do actually value truth so much, why is the world so full of untruth? Why do we lie to others so often? Why do we search for arguments and facts that confirm our biases? Why are we so capable of lying to ourselves?

Ironically, Plato was amongst the first to accept the necessity of telling untruths. In the Republic, the same work in which he writes with breathtaking beauty about the eternal value of truth, Plato argues that the Philosopher Kings of a city may often have to tell “noble lies” to the citizenry to keep them in line. Later, Machiavelli would claim that good rulers must know how to lie effectively if they are to maintain a stable political order. Joseph De Maistre, one of the founders of modern conservatism, argued that the citizenry must never be allowed to look too deeply into the truth of what legitimates a given political order. If they did, citizens might well decide the political order was illegitimate and resolve to overthrow it, bringing about violence and destruction.

The authors above make the interesting observation that in some respect the stability of a general political order depends on telling untruths. But one can also think of more local contexts in which the stability of inter-personal relations, even of a very intimate kind, depends on a degree of dishonesty or at least withholding the full truth. Virtually everyone can think of a situation where being fully honest with a loved one, or an employer, or a child, would generate disastrous results. Indeed, such a world would be so extremely foreign to us it has been presented as a fantasy in films like Liar Liar and The Invention of Lying. More tragically, literary works like Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot present dark parables of what happens to fully honest people in a dishonest world such as our own.

Finally, Nietzsche famously observed that the value of truth and rationality has far too often been overestimated. Nietzsche claimed that many people will never be able to get far beyond the false or banal opinions of the “herd” because they are either intellectually or psychologically incapable of facing the truth of reality as it is. There is little of interest to be said about the first kind of person, who is simply intellectually incapable of understanding the truth of the world. More interesting is Nietzsche’s observation that even the intelligent, who are capable of the thinking necessary to see the world as it is, will nonetheless find ways to delude themselves. As an atheist, Nietzsche often pointed to religious belief as a paramount example. Take Kant, for instance, who, as I mentioned earlier, preached about our moral obligation to tell the truth. Nietzsche condemns Kant for developing very powerful arguments against the existence of God, but then insisting that one must believe regardless because it is necessary to stabilize our moral beliefs. Or contrast the liberal argument that we all possess an innate dignity and worth with the scientific observation that we are just complex forms of matter in motion. These two positions seem mutually exclusive, yet many hold to both concurrently. For Nietzsche, this willingness to accept untruths about reality to preserve our moral beliefs (especially when they flattered our sense of self-importance), is a paradigmatic instance of being unwilling to face the truth that we exist within a meaningless world.

Nietzsche goes on to observe that this tells us a great deal about the human relationship to truth. Very few of us can actually deal with too much truth, so we rarely enquire too deeply into the justifications for our beliefs. And in some respects this may be socially useful. An intelligent and truly honest person would feel compelled to have true justifications for all of their myriad beliefs, and would soon find themselves staring into an abyss of questions which would never end. Take the example of trying to justify why we prefer to live rather than to not exist. Many of our moral dictums are predicated on a belief that life is preferable to death. But if asked to justify this position, many of us would likely struggle to give some uncontroversial answer as to why life has any value in and of itself. We would probably end up appealing to cultural norms, pointing to evolutionary drives built into our genetic makeup, or simply expressing a subjective preference for being alive over not existing. These are likely enough for practical human purposes, but they are hardly a “true” answer to why life has any value in and of itself.

Conclusion

I think that Nietzsche was right in his appraisal of the human capacity to face the truth of reality as it is. On an everyday basis, many of our beliefs rest on suppositions, tradition, and the fulfillment of our emotional needs. This is true even of figures who pride themselves on their rationality and willingness to face the world as it is, warts and all. Consider a scientist who is asked an unusual question. They are not asked whether or not science gives us access to the truth of reality. Instead, they are asked to given an account of the value of science. Why should we prefer true scientific explanations of reality over untrue, but potentially more gratifying narratives? Indeed, the history of scientific progress is beset by such problems. Earlier mythological conceptions of the world placed human beings at the center of the universe as God’s favored creation. With the Copernican revolution we lost of our place at the center of the cosmos. With the advent of Darwinian evolutionary theory, we were forced to recognize that we were but one more species in a long chain going back countless generations. Both of these scientific realizations stripped human beings of our narcissistic conceit about being the axis of creation, but few would say this was a pleasant acknowledgement.

So why should we value the scientific narrative with its indignities over the mythological one? This is a more complex question that it might appear. Once one moves past all the contingent explanations about the use of scientific discoveries for the satisfaction of subjective human desires, one typically sees appeals to the intrinsic value of scientific discovery and the beauty of a true conception of the world. In some respects these are powerful answers, and I largely find them convincing. But there is no doubt that appeals to the satisfaction of human desires or feelings about the intrinsic beauty of scientific truth can be further challenged. Why is it important for human desires to be satisfied? Why should we regard the sense of satisfaction we have at arriving at a true conception of the world as of any fundamental importance? What if it turned out that the meaning of everything turned out to be nothing of great interest at all?

I ask these questions not to attack the value of truth, any more than that was Nietzsche’s intention. To my mind the value of truth is exceptional. Indeed, as mentioned earlier, I am concerned our society is entering an “Age of Bullshit” where we value our biases and prejudices over rational and honest discourse aimed at arriving at truth. My hope was that this article would provoke reflection not just on whether we value the truth, but why and in what contexts.