History

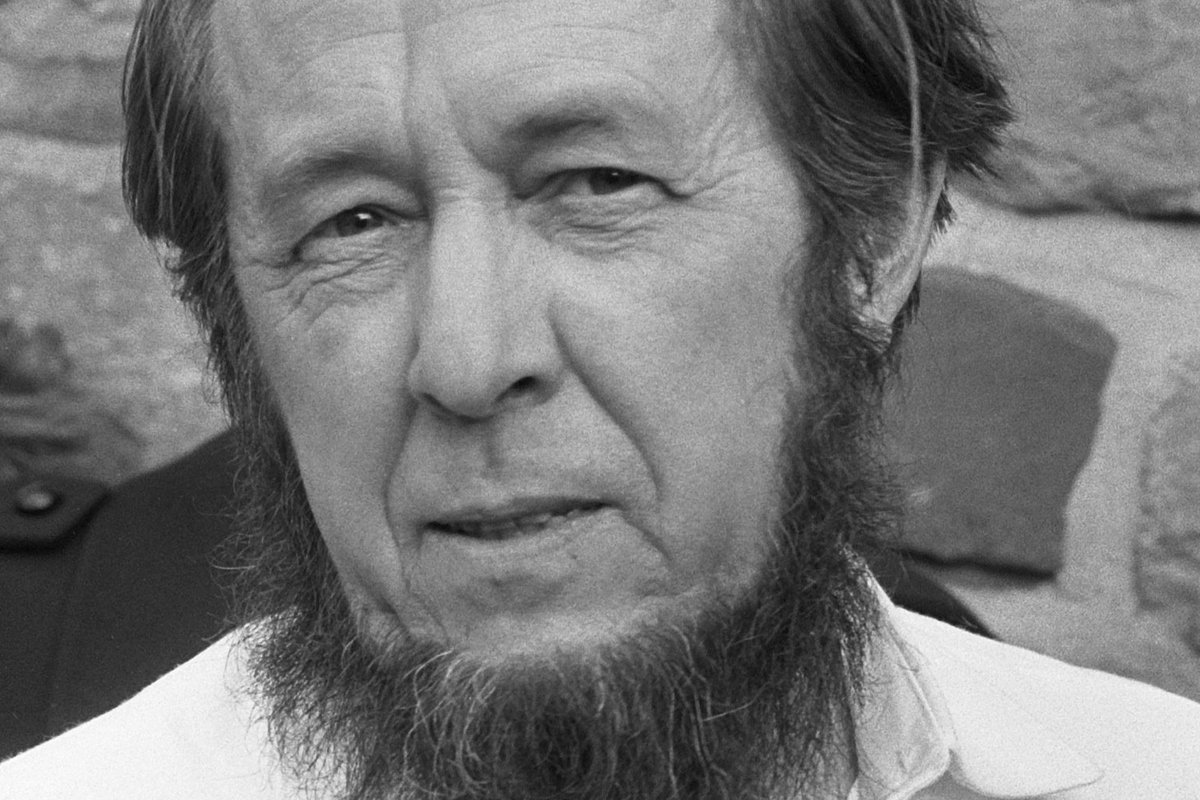

Solzhenitsyn: The Fall of a Prophet

In exile, Solzhenitsyn turned to harsh criticism of the West, not just for failing to stand up to the Soviet regime and fully confront its malevolence.

The 100th anniversary of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s birth on December 11 was an occasion for many tributes. A decade after his death, Solzhenitsyn remains one of the past century’s towering figures in both literature and public life. His role in exposing the crimes of the Soviet regime is a historic achievement the magnitude of which can hardly be overstated. But his legacy also continues to be the subject of intense debate among people who share his loathing of that regime—and those controversies, which have to do with freedom, traditional morality, and nationalism, are strikingly relevant to our current moment.

Solzhenitsyn was once my childhood hero. Growing up in the Soviet Union in the 1970s, in a family of closet dissidents, I knew him as the man who defied the system and told the truth about its atrocities—the man idolized by my parents, especially my father, himself the son of gulag survivors. I was eleven when Solzhenitsyn was arrested and expelled from the Soviet Union; our Stalinist political instructor at school bellowed that he should have been shot as a traitor. A year or two later I heard excerpts from The Gulag Archipelago on foreign radio broadcasts; then, the coveted book appeared for a short while in our home.

Later, after my family emigrated to the United States in 1980, Solzhenitsyn’s heroic halo gradually began to lose its luster in our eyes. We were hardly alone; as the years went by, many of his erstwhile admirers came to believe, with bitter disappointment, that Solzhenitsyn could no longer be seen as a champion of freedom and justice.