Europe

'Luciferina': An Interview with Amanda Knox

Knox found the fortitude to survive her crucible and the talent to start over. Hers is a voice I will definitely be waiting to hear more of.

Though the Republic of Italy has been secular since 1985, on the wall above the judge in the Perugia courtroom hung a giant black crucifix. The main prosecutor, Giuliano Mignini, thundered at the then 22-year-old American defendant, Amanda Knox, on trial in 2009 for the murder, two years earlier, of her British roommate in Perugia, Meredith Kercher, calling her, Knox remembers, a slut and an adulteress. A lawyer involved with a related civil suit dubbed Knox “Luciferina” — a satanic slur that soon found its way into press coverage of the matter. And it stuck.

Os acordáis de Amanda Knox?

— MirEdeC (@MirEdeC) October 21, 2016

Luciferina, satánica, demoniaca, diabólica: una bruja sexual?

Esa esa https://t.co/bYhU7p2NJg

Another Italian lawyer denounced Knox publicly as a “dirty-minded she-devil, a diabolical person focused on sex, drugs, and alcohol, living life to the extreme,” and “a witch of deception,” “Lucifer-like and Satanic,” yet who possesses the face of a saint. An Italian commentator declared that Knox had “the face of an angel but the eyes of a killer.” In reference to her looks and supposedly scheming character, British tabloids (soon followed by the Italian press) dubbed her “Foxy Knoxy”—though the moniker dated from her childhood and originally referred to her skill as a soccer player. Even the usually staid BBC saw fit to wonder “what was really going on behind [the] smile” of “the beautiful young murderess.”

A distinctly religious, sexist spirit pervaded almost all the portrayals of Knox so freely proffered in the media. Not so with Raffaele Sollecito, Knox’s Italian boyfriend at the time and her alleged accomplice. He garnered only a fraction of the press she got, though he was convicted with her. (A young man of Ivorian descent with a criminal record, Rudy Guede, was also convicted of the killing in 2008 and sentenced to 16 years imprisonment. He received the least press of all.) The Italian media and prosecutors ceaselessly focused on what, for them, was the case’s key element: the supposed moral depravity of a beguiling young American beauty, understood to be non-Catholic and thus implicitly embodying corrupt, godless values—just the sort of evil temptress who could orchestrate and oversee the rape and murder (by Sollecito and Guede) of an innocent young woman.

Scandalously, although DNA and other evidence had implicated Guede and indicated that he had acted alone, the Italian authorities focused relentlessly on Knox and Sollecito—with the media especially fixated on Knox. The resulting judicial tribulations the two suffered know few modern equivalents. Concerning Knox: She was arrested for murder in 2007, convicted in 2009 and sentenced to 26 years behind bars (one year more than Sollecito); acquitted on retrial and released in 2011; retried (in absentia) in 2013 and convicted again; and, finally, absolved unequivocally in 2015 by Italy’s Supreme Court of Cassation.

Last week, the disarmingly fresh and friendly face of Amanda Knox appeared on my computer screen as we began our talk via Skype for this article. She spoke to me from her home in Seattle.

“I didn’t condemn religion before my trial,” Knox said. “But religion is a manifestation of tribalism, and I was not part of that tribe. I was vilified for not being a good Catholic chaste girl.”

During our 132-minute, wide-ranging talk, Knox showed herself to be articulate, progressive, outgoing, funny, and surprisingly without bitterness over the four years (including eight months of solitary confinement) she lost to an Italian prison for a crime she had nothing to do with. Now 31, Knox told me that this was the first time she was publicly speaking out about her atheism and opposition to religion, which she views as an ideology that leads to “othering,” fosters tribalism, and is, of course, “based on believing something just because you want to believe it. . . . Religion is an ideology that allows you to demonize others. . . . Atheists constantly interrogate their views.” She said that being criminally tried beneath a “giant crucifix was extremely intimidating.”

“Religious scenery was on the walls. I knew I was in a medieval building that was culturally and historically religious. They were burning people at the stake just outside the doors!” Nevertheless, Knox volunteered that the “only real nonjudgmental support” afforded her behind bars came from Don Saulo, an elderly priest in residence whom she described as “deeply compassionate and caring.” He never tried to convert her to Catholicism, but Don Saulo let her spend time in his office, ostensibly to practice guitar-playing for Sunday mass, but also to listen to the Beatles with him and give her a break from cell time. Moreover, according to Knox, Don Saulo frequently approached Mignini in the courthouse cafeteria and told him “you’ve got Amanda all wrong.” The nuns visiting her, however, treated her harshly, warning her that “people without faith were “no better than animals, that faith was what differentiated us from animals.” For Knox, though, the “idea of good and evil that comes so easily to a religious mindset” was “not compatible with what [she] understood about human beings.”

I asked what she thought of Mignini and his courtroom diatribes against her, which he delivered in florid, often religious terms.

“His worldview was largely rooted in Catholicism . . . in law and order and divine law. He said I had the face of Santa Maria Goretti but a double soul. He called me ‘Luciferina’ and a femme fatale. . . . I was a manifestation of how Lucifer could infiltrate the innocent, that I was evil for the sake of evil. How could you argue rationally against that? He characterized me as a whore who would do anything for sex, even murder, a rampant whore, a diabolic scheming manipulative jealous whore, obviously Satanic. . . . I was the one who used my feminine powers to bewitch men and make men rape Meredith for me, I was the mastermind who instigated it all, and that these young men would never have done it, if it weren’t for me.” She added, that, “It’s not like the Catholic Church went in and condemned me. But it was an environment where Catholic ideas about female sexuality and about sexuality in general and about what roles women are supposed to play . . . were part of this perfect storm for creating a story to put an innocent person in jail.” Mignini presented his case against her in religious language because it “resonated with people. Otherwise, [his accusations] wouldn’t have had an impact.”

Mignini accused Knox of organizing “a Satanic orgy” during the course of which Kercher, unwilling to take part, was raped and murdered. His depiction of Knox, she said, consisted of “intimate misogynistic bullshit” that “confirmed people’s prejudices,” and showed an “absolute willingness to vilify my sexuality.” For him, women were “either whores or Madonnas, and whores are always asking for it.” She contended Mignini was “projecting his fears and fantasies onto [her].”

Clearly Mignini knew his audience. On a continent that has long been losing its faith, Italy remains one of Europe’s most devout countries. Hoping to take advantage of this, Knox’s lawyers urged her to wear a cross to court. She refused. At no point in her life had she ever believed in God. She attended a Jesuit high school, but when her teacher asked her class to write about why they were “good Christians,” she responded with a rebellious essay in which she, tongue-in-cheek, declared herself “a practicing pagan” who “worshiped the moon nakedly in [her] back yard.”

Knox sounded defiant to me, but dark moments followed her arrest. They included sexual harassment from a male guard, lewd questions from the vice-commandant of the prison during lengthy, one-on-one encounters for which he called her to his office, and an unwanted kiss from a female cell mate. She contemplated suicide in the weeks after her conviction, when, she wrote me in an email subsequent to our talk: “My world collapsed. I realized that my innocence hadn’t saved me, that everything I thought my life would involve (love, family, travel, career) had been taken from me.” She and her fellow prisoners knew they could take their lives with a “garbage bag and a gas canister” or use a broken pen to slit their wrists in the shower. “I don’t think I ever got close to hurting myself, but it was important to me that the option was there.”

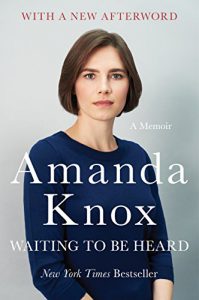

After her release from prison, Knox wrote numerous essays for many publications, including the L.A. Times and USA Today, and published a bestselling memoir about her ordeal in Italy, Waiting to be Heard. The $3.7 million advance she received for the book mostly went to paying off her legal fees and her parents’ trips to Italy to support her emotionally, but also allowed her to finish university. (Her parents always ensured a family member was in Perugia while she was in prison, though the authorities only allowed six hours of visitations per month.) Knox has also sparred publicly with Donald Trump. Trump had weighed in on her case in 2011, proclaiming her innocent and calling the Italian prosecutor a “maniac” and a “whacko.” Once Knox was free and Trump had won the presidency, he was reportedly “very upset” that she had declined to vote for him. In an editorial published in the L.A. Times, Knox thanked Trump for his support but explained that her “politics hinge on the merits of policy, not personal loyalty,” and that what counted for her was “loyalty to our ideals of due process, equal protection under the law, the freedom to speak one’s mind and to vote according to one’s principles.” Earlier this year, Knox began hosting “The Scarlet Letter Reports”, a video series that runs on Facebook Watch (in partnership with VICE Media) and delves into the stories of women who have been publicly shamed and demonized.

Knox found the fortitude to survive her crucible and the talent to start over. Hers is a voice I will definitely be waiting to hear more of.

Editor’s note: November 30, 2018

The opening paragraph has been edited for clarity.