Art

Sabrina the Woke Witch is a Disgrace to Baphomet

Whether on-screen or off, humans are interesting only when they assert moral autonomy over their own lives.

Like many Canadian teenage girls who came of age in the 1990s, I grew up on 2% milk, dime-store candy and tales of the occult. I was slightly too old for the Harry Potter craze, falling instead for Buffy the Vampire Slayer and films such as The Craft. One of my special favorites was Sabrina the Teenage Witch, an ABC series about a magical American teenager who lives with her 500-year-old aunts and a talking cat.

Witchcraft fascinated me. When girls reach that liminal time between child and woman, our bodies transform—and, with them, our sense of control. It’s a strange thing to go from being cosseted and encouraged to desired and despised. It feels a little like dark magic—though not the kind one can control. Unless, of course, you are a witch.

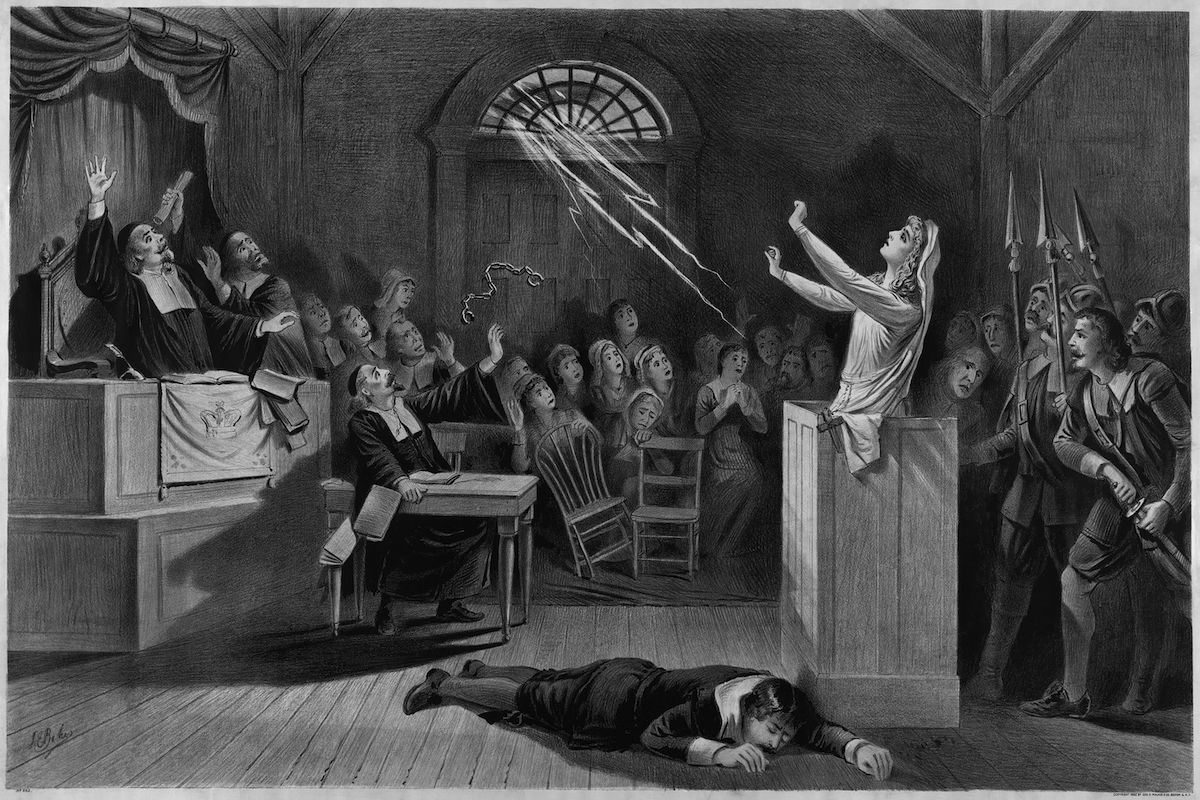

Like the magical artifacts Harry Potter is always stumbling upon, witchcraft offers power. It promises a way to re-shape the world to a girl’s advantage, to gain freedom from parents, to toy with boys’ hearts while numbing one’s own. Male magic fantasies tend to be centred around power and combat—with lightning perpetually emanating from wands and fingertips into the chests of adversaries blown backwards. However, the sort of witchcraft that interests me is more subtle, and sometimes passes unseen. (In real life, such powers originate in sex—but it takes time for a girl to learn that.) It’s no coincidence that the world of witchcraft becomes a dark mirror of our society, reflecting the dispositions and paranoias of our times. When times are good, the witch is portrayed as a benign, bubbly figure; when they are not, the witch becomes malevolent and dark, in line with medieval lore.

The 15th-century Malleus Maleficarum portrayed witches as horrific creatures populating the devil’s harem. But today’s witches have received the same makeover that Edward Cullen gave male vampires in the Twilight books. Networks and studios have learned that powerful, sexy women are fun to watch, for adult women as much as girls. And so when the 10-episode first season of the latest Sabrina reboot was released by Netflix last month—Chilling Adventures of Sabrina—I binged.

I know it’s unfair to expect any show to rekindle the magic I first felt watching Bonnie, Nancy, Rochelle and Sarah exacting magical revenge against terrible boys in The Craft. But even with this in mind, Chilling Adventures of Sabrina seems shockingly flat, and even regressive. Overarching themes of goodness and free will are garbled from one episode to the next. Characters are poorly defined. Subplots flounder. What’s worse, Sabrina ruins the very idea of witchiness, turning it into just another flavor of puritanism.

* * *

Our protagonist is the teenage Sabrina Spellman, half-mortal, half-witch. (The name derives from the original Sabrina, whose exploits first appeared as part of the Archie comic universe of the early 1960s.) At the age of 16, she is required by witch law to sign her name in the Book of the Beast during a midnight Dark Baptism in the woods near her house. Yet despite her upbringing as a witch, she harbours serious doubts about whether she should dedicate herself to the Dark Lord.

Sabrina eventually goes to witch school. But this is no chaste Hogwarts-style academy. When Sabrina walks into the Academy of Unseen Arts, she is confronted by a bizarre, darkened complex whose architecture is ruled by “sacred geometry.” Each room is built around a central pentagram that stretches into a seemingly infinite number of classrooms and dormitories. At the centre sits a tall, stone Baphomet—the goat-headed deity that is neither male nor female, both saintly and debased. Two fingers point to the sky and two to the ground. At Baphomet’s feet, stand two children.

A Satanist should recognize the statue instantly—as it is similar to the famous Baphomet created by 19th century occultist Eliphas Lévi. Moreover, the statue used in the show appears to be almost identical to a work commissioned by the modern-day Satanic Temple, a religious and political activist group based in (where else?) Salem, Massachusetts.

The Satanic Temple had created their own eight-foot-high statue with the intent of placing it next to a monument of the Ten Commandments at the Oklahoma State Capitol. It was a glorious act of secular trolling, intended to highlight the importance of separation of church and state. Ultimately, it was unveiled at a raucous 2015 party in Detroit, starring two men in leather fetish gear who embraced passionately at the moment the white sheet was pulled away and the crowd was given a glimpse of their goat god. It’s little wonder that The Satanic Temple took issue with a Bapho repro appearing in a show as prudish and anti-Satanic as Sabrina. Shortly after the show aired, the Temple filed suit against Netflix in a New York court, claiming $150-million in damages for copyright infringement, trademark violation and injury to reputation. (Update: The law suit now has been settled. )

Throughout history, Baphomet has been depicted and interpreted in a bewildering number of ways, but usually in some manner that symbolizes a departure (or liberation) from established Christian cant. In his 1850s-era work, Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie, Lévi described the folk version of Baphomet as “that phantom of all terrors…the nightmare, the Croquemitaine [bogeyman], the gargoyle, the great beast of the Middle Ages, and—worse than all these—the Baphomet of the Templars, the bearded idol of the alchemist, the obscene deity of Mendes, the goat of the Sabbath.” But Sabrina is in many ways the opposite of all this—for she is the least transgressive character imaginable: punctiliously progressive and woke, endlessly enlightened in her feminism, and uncompromising in her hatred of the unjust and patriarchal school principal who presides over Satan U. The world of witchcraft that Sabrina is fighting is portrayed by the show as something evil and vicious, infected with dogma, rigidity, and even cannibalism. You can see why the Satanic Temple would be furious.

* * *

Satanism, which originally was conceived as the biblical opposite of true Christian belief, now blurs into gauzy new-ageyness. As defined by Anton LaVey, 1960s-era founder of the Church of Satan, Satanism is an anti-hierarchical creed that is somehow both non-theistic and supernaturalistic. Its philosophy is deeply grounded in individualism, pleasure-seeking and at times even ruthlessness. Satanists cut from this cloth value physical autonomy and private property, respect the lives of animals and children, they reject conformity and pretension.

From the Church of Satan emerged the above-mentioned splinter group—the media-savvy Satanic Temple—in 2012. The Temple prioritizes a scientific world view and focuses on modern political issues, such as reproductive autonomy for women, and the protection of America’s church-state divide. The Satanic Temple also is explicitly devoted to exposing the kind of sham psychological practices that led to the satan-worship social panics of the late 20th century. Unlike the Church of Satan, the temple preaches compassion and empathy, and rejects all forms of supernaturalism. According to this understanding, Satan exists as a metaphor for rebellion against the tyranny of God.

It is difficult to pin this kind of Satanism on the ideological spectrum. Many of the Satanic Temple’s values and campaigns align with progressive and leftist causes. But much of its underlying philosophy is almost akin to libertarianism. It bears no resemblance to the demonic stereotype embodied by Sabrina’s oppressors, nor to Sabrina’s own orthodox Wokeness.

There is a brief moment when the Chilling Adventures of Sabrina seemed to be on the right track. It comes in the opening sequence of the second episode, where Father Blackwood, High Priest of the Church of Night, is summoned to ease Sabrina’s doubts about her Dark Baptism.

“Your aunties tell me you have questioned about your Baptism and such,” he says.

“I do,” she responds. “But I’m not sure where to begin.”

“Allow me. A witch’s dark baptism is our most sacred unholy sacrament. The oldest of our rites, we have been performing them for centuries,” he says, explaining that the ceremony will mark the moment when she pledges submission to the 13 Satanic commandments.

“But the Devil… He’s the embodiment of evil,” Sabrina protests.

“Incorrect! He’s the embodiment of free will. Good, evil, those words matter to the false God, but the Dark Lord is beyond such precepts…really what’s needed here is a fundamental shift in thinking,” Father Blackwood says. Free choice, he insists, that is the bedrock on which the dark church is built.

This was the sort of conversation that might have led to an exploration of the free-thinking rationalism of actual Satanists—and even a teen-level examination of the old philosophical and theological problems associated with reconciling God, determinism and free will. This would have created a legitimately compelling and interesting arc—one in which Sabrina is forced to embrace either the good-versus-evil dogmas of the mortal world, or the dark uncertainty of a faith that lionizes free will and power lust.

In this alternative version of the new Sabrina franchise, in other words, The Church of Night would not present us with the evil opposite of our conventional moral world, but rather something entirely distinct. But the creators weren’t up to the challenge—and instead turned Sabrina into a muddled sort of Luke Skywalker of Wokedom battling against a Darth Vader of patriarchy and privilege. What’s worse, there’s no air of mystery about Satanism: By the end of the second episode, it’s clear that the Dark Lord is just a collector of souls and a liar. The Church of Night is coercive and evil, a den of cannibalism and, likely, child murder.

It is, in other words, a shockingly old-fashioned Christian view of Satan, with the Church of Night playing a goth parody of Catholicism. But Christianity itself plays no actual role in the plot. Instead, the Good News of redemption comes via a school club Sabrina establishes with her friends, which they call—seriously, I am not making this up—the Women’s Intersectional Cultural and Creative Association, or WICCA.

* * *

Chilling Adventures of Sabrina first took shape in a 2014 Archie Comics imprint called

Archie Horror. In these books, there was no subtlety: The witches are murderous, cannibalistic, amoral—and hideous. The story is straightforward and tragic, as comics should be. No, you’re not going to learn any real history about Baphomet. Nor will you get a modern political lecture: Comic-book Sabrina makes no attempt to be intersectional.

In her televised form, by contrast, Wokeness takes center stage. Sabrina’s boyfriend comes from a family of working class miners (classism: check). One of her friends is a woman of colour who is losing her eyesight (race: check. Ableism: check). The other is gender non-binary (check). These supporting characters mostly lack interesting back stories. They act as enablers for the white, female protagonist to act as a great ally. Sabrina is a good witch because she defends and loves her less privileged friends in a super-intersectional way.

The most confusing character in the series is Ms. Mary Wardwell, ostensibly Sabrina’s high school teacher. As the series progresses, it is revealed that she is an avid and devoted follower of the Dark Lord. Yet she is also the most overtly feminist character in the entire series—at one point fighting the repressed school principal to grant her students access to banned books.

In the 2014 comic version, Ms. Wardwell is simply an angry woman who seeks vengeance on Sabrina and her family because she was romantically rejected by Sabrina’s father. In the show, however, Ms. Wardwell goes to elaborate lengths to manipulate Sabrina into signing her name in the Book of the Beast. She resurrects the souls of dead witches, who come back from the dead to haunt the town of Greendale, seducing Sabrina into pledging her soul in exchange for the power to save the town. She says one of her most poignant lines in the series when Sabrina stands before the book itself. “All women are taught to fear power. Own your power, don’t accept it from the Dark Lord, take it wield it. Save your friends,” she implores.

Sounds interesting, right? But—spoiler alert!—in the final episode, Ms. Wardwell admits her true motives: The most powerful, feminist character is even more phallocentrically evil than anyone could ever have suspected: Her sole purpose all along has been to manipulate Sabrina into an eternity as maidservant to a patriarchal deity. As Sabrina’s doomed principle quivers in fear, Ms. Wardwell launches into a final monologue: “I am the Mother of Demons. The Dawn of Doom. Satan’s concubine. I am Lilith, dear boy, first wife of Adam, saved from despair from a fallen angel. I call myself Madam Satan in his honour and soon, very soon, I will have a new title. You see, once I finish grooming Sabrina to take my place as Satan’s foot soldier, I will earn a crown and a throne by his side. Who am I? I am the future Queen of Hell.”

Traditional church-goers might blush a little at these alt-bride-of-Christ goth theatrics—just as the woke might recognize a perfect send-up of cynical white feminism. For here we have a vested white woman using the language of empowerment to induct a young woman into continuing a repressive male power structure. Madam Satan is assuming all the trappings of patriarchy to assume power, albeit a power whose scope shall forever be defined by a male master’s orders. She is the corrupter of souls, the ultimate gender traitor. And so it makes perfect sense that after 10 episodes paying homage to Wokedom, this is who the biggest villain turns out to be. Like the plot of a bad TV show that swallows up its only interesting plotline, Ouroboros-style, this is where Wokeness seems to lead us: right back to the dogmatism that marked the most puritanical interpretations of Christianity. Powerful women are evil. Got it.

Whether on-screen or off, humans are interesting only when they assert moral autonomy over their own lives. But Sabrina is merely a pawn of more interesting and powerful characters. She has no true free will. Her world is one in which the only choice is to follow someone else’s dogma—the religious dogma of goat-head-worshipping anti-Christians, or the secular dogmas of well-intentioned Wokeness. At the end of the day, the conceit that young viewers might be inspired by this false dichotomy is what makes Sabrina’s adventures so “chilling.”