History

My Misspent Years of Conspiracism

Conspiracy theories foreclose the possibility of explanation, because they postulate unalterable conclusions in search of evidence instead of following evidence to plausible conclusions.

I.

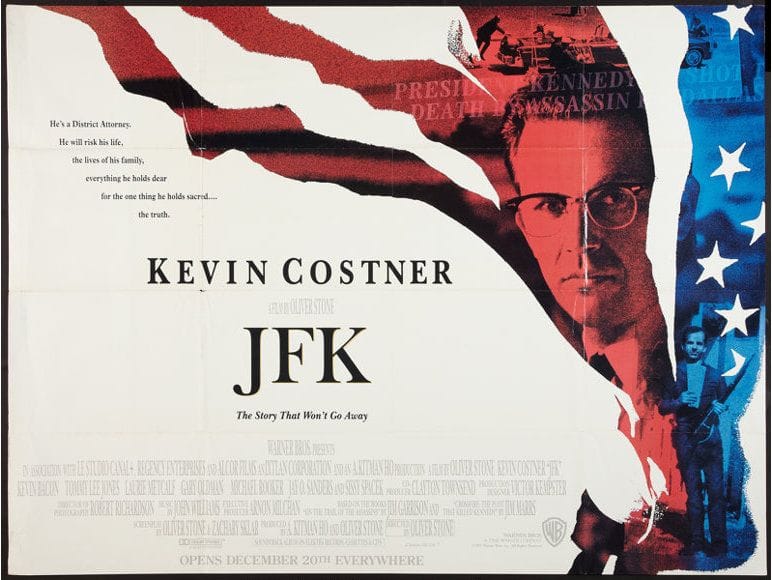

My tumble down the JFK assassination rabbit-hole began in the Tunbridge Wells Odeon on 25 January 1992. I was 16. A few years previously, I had watched a television documentary that purported to identify a second assassin in police uniform (known to conspiracy researchers as ‘badgeman’) firing at the president from the grassy knoll. But I’d never heard of Jim Garrison and knew precisely nothing about the case he had prosecuted against Clay Shaw. Oliver Stone’s new film had a 189-minute running time (later expanded to 206 minutes in the Director’s Cut) which struck me as excessive, and there was something vaguely irritating about the piety of the sentences emblazoned across the promotional material (“He is a District Attorney. He will risk his life, the lives of his family, everything he holds dear, for the one thing he holds sacred… the truth”). Nevertheless, on JFK’s opening weekend, I took my seat in a packed auditorium along with a couple of school friends and for over three hours I was mesmerised. By the time it was all over, my misgivings had been forgotten and I was convinced.

I would see Stone’s epic a further four times on the big screen. My school’s film club showed it, I persuaded my American politics teacher to take our class to see it, and I dragged my younger brother to watch it twice, the second time with our sceptical father in tow. My father was unimpressed. Jim Garrison, he tried to explain, was an unscrupulous charlatan. And the long and sinister monologue authoritatively delivered by Donald Sutherland’s mysterious X on a Washington bench should probably be disregarded until we can ascertain who this person is. (X has since been identified and the news, from a credibility standpoint, was not good.) To my annoyance, my brother wasn’t sold on Stone’s hypothesis either. He found the film manipulative. “I just don’t trust Oliver Stone,” he shrugged, and moved on with his life.

Undeterred, I got my hands on a copy of Garrison’s memoir On the Trail of the Assassins and was reassured to find that Stone’s film tracked his account closely. Stone and his co-screenwriter Zachary Sklar had combined some of the dramatis personae into composite characters but, overall, their adaptation was remarkably faithful to the source, from which much of the script had been lifted verbatim. The details of the case against Clay Shaw remained opaque to me (which, in retrospect, ought to have been a clear sign that something was amiss), but I thought it perfectly obvious that the Warren Commission’s conclusions were absurd. No self-respecting person could accept an explanation of the assassination that required a bullet to manoeuvre in mid-air (“where it waits 1.6 seconds”), for no apparent reason other than to preclude the possibility of a second rifle. And the Zapruder film clearly showed Kennedy’s head being propelled backwards and to the left, which suggested a gunshot from somewhere in front of the car, not from the Texas School Book Depository behind it. Even my father reluctantly conceded that the most persuasive part of Stone’s film was its contention that the alleged assassin Lee Harvey Oswald could not have done the shooting by himself.

I found all this chilling but strangely exhilarating. Part of that exhilaration was no doubt a reflexive response to the relentless aggression of the film itself—JFK is a dazzling political thriller, clattering through Garrison’s investigation and sundry other speculations with pulverising conviction and an infectious urgency bordering on panic. There was also, I suspect, something perversely exciting about the plot itself that offered me a pleasurable frisson of transgression—not only had the conspirators executed a plan of breathtaking audacity, but they had got away with it in front of everyone. I was enthralled by the mystery and the mayhem they had left in their wake.

However, Stone’s film also offered an appealingly simple and far-reaching explanation for how the world works. “The organising principle of every society, Mr. Garrison, is for war,” pronounces X. JFK demanded that we re-understand everything, but I didn’t have much to re-understand aged 16. Stone simply aggravated my pre-existing anti-authoritarian reflex and flattered my adolescent cynicism by confirming what I already suspected—that power is pitiless, self-serving, and corrupt; that the good die young and the wicked prosper; and that those of us clever enough to understand harsh truths like these had a responsibility to expose them. Here, I decided, were profound insights and moral clarity.

The intensity of my obsession burned itself out in a year or so, and my mind moved on to other things. But I took what I had learned for granted and incorporated it into my developing worldview. This led me straight into the arms of Noam Chomsky, whose books and articles I would devour in the university library and whose arguments about manufactured consent and American moral turpitude I would then churn into unimaginative essays. The state-sponsored liquidation of JFK certainly fortified my view that America was no better than its enemies, and allowed me to denounce the West more generally for the usual list of disgraceful crimes and moral hypocrisies. I felt proud of my perspicacity and altogether superior to those indolent somnambulists (everyone else) who believed the mainstream media and failed to understand the importance of asking “Who benefits?”

This view survived more or less undisturbed until 22 November 2003.

II.

John Fitzgerald Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States, was shot to death on the afternoon of 22 November 1963, as his motorcade rolled through Dealey Plaza in Dallas, Texas. Kennedy was en route to a luncheon at the Trade Mart where he was scheduled to speak. Texas Governor John Connally, seated in front of President Kennedy in the presidential limousine, was also seriously wounded in the shooting. Later that day, a 24-year-old Marxist named Lee Harvey Oswald was arrested at a Dallas movie theatre and booked for the murder of Dallas police officer J.D. Tippit. By the following morning, he had also been booked for the murder of the president. Then, two days later, Oswald was himself assassinated by local nightclub owner Jack Ruby as he was being moved to the county jail. Rumours of a conspiracy and cover-up duly swept the reeling nation.

On 29 November 1963, President Lyndon Johnson issued an executive order establishing a commission headed by Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren to investigate the assassination. This, it was hoped, would bring all the available facts to light in the absence of a trial, reach the appropriate conclusions about culpability, and uncover any accomplices should they be found to exist. When the Warren Commission finally issued its report on 24 September 1964, it had concluded that Lee Harvey Oswald had shot and killed both President Kennedy and Officer Tippit, and that he had acted alone. He had fired three rifle-shots from the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository where he worked, killing Kennedy and wounding Connally. He had then fled the scene and shot Tippit three miles away using a .38 revolver.

But rumours of conspiracy persisted. Amateur sleuths and researchers pored over the Warren Commission’s findings seizing on apparent inconsistencies and lacunae, and in August 1966, Mark Lane’s Rush to Judgment appeared and became an instant bestseller. It was among the first of over a thousand books by a dedicated contingent of critics which derided the Warren Commission as either incompetent or somehow complicit in a cover-up. In 1967, New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison would bring the only prosecution in the murder of President Kennedy, and it was this case that Oliver Stone would later dramatise in his wildly successful blockbuster. Stone’s film mainstreamed fringe theories at a stroke, and hasty reissues of conspiracy literature, including Garrison’s own account, flooded airport bookstores.

By 2003, somebody at the BBC had evidently decided enough was enough, and on the 40th anniversary of the assassination, it broadcast an 85-minute documentary entitled Beyond Conspiracy that promised to clear up the muddle once and for all. “You can talk about all the theories you want,” an interviewee confidently declared in the trailer. “This thing only happened one way.” I was excited to hear this. It never occurred to me that anyone would be foolish enough to produce a film defending the Warren Commission’s discredited findings at this late date. But that was what I found myself watching. And to my gathering dismay, it was much better than expected.

Beyond Conspiracy was written and directed by Mark Obenhaus, and presented by British broadcaster Gavin Esler. (The version screened in the US was identical, but the voice-over was provided by ABC’s Peter Jennings.) It’s a masterpiece of methodical argument, patiently picking its way through the case and marshalling the facts. Within 15 minutes, it had become apparent that I didn’t know nearly as much about the assassination as I thought I did. Like most JFK conspiracy enthusiasts (including, it now seems to me, many of those who have published whole books on the topic), I had never bothered to read the 888-page Warren Report, let alone trawl through its 26 volumes of supporting evidence and testimony. But nor had I bothered to read any books by people who had, and who could be trusted to provide an accurate account of their contents.

So, during the documentary and my subsequent reading, I was taken aback to discover that the case against Lee Harvey Oswald was a good deal stronger than I had been led to believe. Here is just some of the evidence against Oswald omitted or misrepresented by Stone’s film:

- On the day of the assassination, Oswald brought a long package wrapped in brown paper into work. He told his work colleague Buell Wesley Frazier that the package contained “curtain rods.”

- That same morning, Oswald had removed his wedding ring and left it in a cup for his wife Marina (which she testified he had never done before), along with $170, which amounted to all the money they had, aside from the $14 in his pocket.

- Multiple witnesses saw Oswald either shooting Dallas police officer J. D. Tippit, or leaving the scene on foot and emptying his revolver of spent shells. Stone draws our attention to conflicting testimony from two other witnesses, but neglects to point out that ballistics matched the bullets in Tippit’s body and the shells recovered at the scene to the .38 revolver Stone acknowledges Oswald collected from his rooming house after the Kennedy assassination. Oswald’s discarded jacket was recovered near the crime scene.

- Both the Mannlicher-Carcano rifle discovered on the sixth floor of the school book depository and the .38 revolver Oswald was still carrying when he was arrested were bought by Oswald using the alias A. Hidell. Identification bearing that name was found in Oswald’s wallet when he was arrested. The revolver was sent to Oswald’s PO Box in Dallas.

- Oswald refused to take a lie detector test.

- Ballistic tests definitively matched bullet fragments in the presidential limousine and the bullet later found on Governor Connally’s stretcher with Oswald’s Mannlicher-Carcano to the exclusion of any other firearm. The three spent cartridge cases found on the floor of the book depository were also matched to Oswald’s rifle. Fibres from Oswald’s shirt were found on the rifle butt. The brown paper bag in which the rifle had been concealed prior to the shooting contained fibres from a blanket Oswald had kept wrapped around the rifle. Oswald’s palm prints and fingerprints were found on the weapon itself, on the boxes stacked below the sniper’s nest window, and on the paper bag. (Stone acknowledges an Oswald palm print on the rifle, but has Garrison speculate, on the basis of nothing whatever, that this was taken from Oswald as he lay in the morgue.)

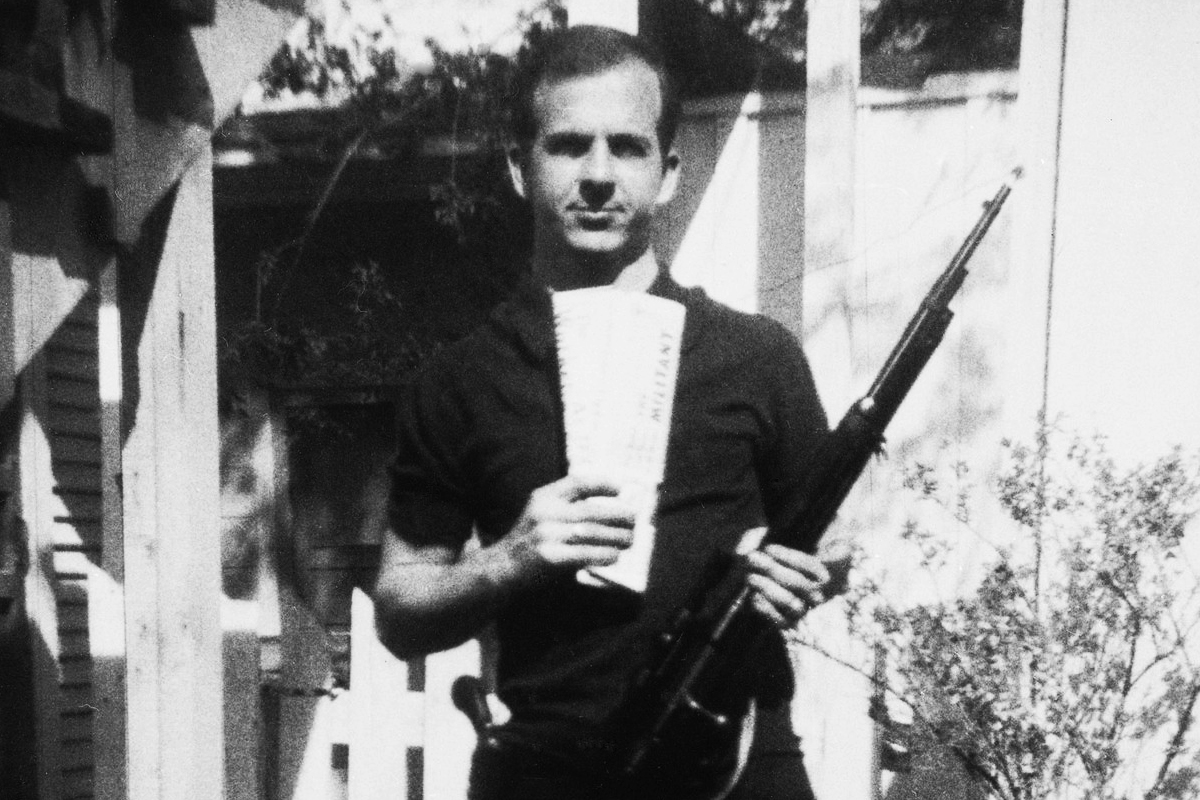

- Stone claims that the three exceedingly incriminating “backyard photographs” of Oswald posing with his guns and communist literature were forgeries. He does not tell us that the photographs have been endlessly authenticated, that Marina testified she took them at her husband’s request, and that expert handwriting analysis identified Oswald as the author of the words “Slayer of Fascists” scrawled on the back of one of them.

This is nothing like a complete inventory of the direct and circumstantial evidence against Oswald, but it seemed to me to be more than enough to secure a conviction.

And that’s just the evidence linking Oswald to the crime itself. Stone and Garrison were similarly selective with respect to Oswald’s biography. In their version of events, Oswald was an American intelligence operative, somehow framed by the conspirators. In reality, copious testimony from friends, neighbours, work colleagues, and acquaintances made it abundantly clear that no sane person would have considered Oswald suitable for intelligence work. A consistent picture emerges of a bitter, confused, violent bully and congenital liar, which is more-or-less how his wife Marina described him to the Warren Commission. (“They taught her how to answer,” Garrison blithely declares in Stone’s film.)

Oswald was a delinquent and truant who hated school and dropped out at 16. He joined the Marines in October 1956, and hated that too. He clashed repeatedly with his superiors and fought with his colleagues. He was court-martialled twice, demoted, and held in the brig. Upon his return home in 1959, he decided he hated America. Declaring himself a communist, he tried to defect to the Soviet Union. When his request for Soviet citizenship was denied, he slit his wrists and was transferred to a Soviet psychiatric ward. The Soviets agreed to let him stay as a stateless person, planted him in a factory job in Minsk, and kept him under surveillance. They quickly established that he was far too unstable to be an American agent and that they had no interest in recruiting him for the same reason.

In Minsk, Oswald met and married Marina Nikolayevna Prusakova and the couple had a daughter. By now he hated the Soviet Union. Having failed in an attempt to renounce his American citizenship and having been denied citizenship by the Russians, Oswald announced in mid-1961 that he wanted to go back to America. Oswald, Marina, and their daughter emigrated in June 1962, and thereafter he complained bitterly about how much he hated America and wanted to return to the Soviet Union. His relationship with Marina deteriorated. Angry, frustrated, perpetually dissatisfied, and unable to hold down a job, Oswald would verbally abuse and beat Marina, sometimes in front of witnesses. His politics became increasingly militant.

At the end of April 1963, Oswald moved back to New Orleans where he had been born and, a month later, he founded a local chapter of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, of which he was the only member. Distributing his literature on the street, he got into a fight with Cuban exiles. After a disastrous local radio debate about the fracas, Marina testified that she would listen to him sit for hours on the unlit front porch at night with his rifle recycling the bolt action over and over again. He became preoccupied with the idea of moving to Cuba, and tried to convince Marina to help him hijack a plane there. In September 1963, he travelled to the Cuban embassy in Mexico City to apply for a visa (Garrison insisted this trip never even happened). Oswald told the embassy officials that he wanted to visit Cuba on his way to Russia, so the Cubans sent him to the Russian embassy to collect a permit to enter the Soviet Union. When it was denied, Oswald burst into tears and started to wave his revolver in the air. Had he ever managed to persuade Cuba to take him, I’m fairly certain he would have hated it there, too.

Perhaps the most egregious omission from Garrison’s book and Stone’s film is that Oswald had already tried to assassinate someone else in April 1963. This information seems relevant, does it not? He had bought his Mannlicher-Carcano rifle and his .38 revolver by mail-order in March 1963, while he and Marina were living in Dallas-Fort Worth. At the end of the month, he asked Marina to photograph him in the back yard with his guns and his copies of the Militant and the Worker. Oswald considered retired US Major General Edwin Walker to be a fascist and had been planning his assassination for months, photographing his quarry’s house and mapping an escape route. On 10 April, Oswald left his post office box key on top of an 11-point list of instructions for Marina in Russian which concluded:

11. If I am alive and taken prisoner, the city jail is at the end of the bridge we always used to cross when we went to town (the very beginning of town after the bridge).

That evening, he shot into Walker’s house with his rifle, but the window frame deflected the bullet past Walker’s head. Oswald returned home and told Marina what he had done. When he later discovered that Walker had survived, he became distressed.

It is perfectly obvious why this kind of information might not enthuse conspiracy theorists, but by ignoring it entirely they reveal the weakness of their hand. Oswald’s erratic behaviour and the evidence linking the bullets to the gun and the gun to Oswald are mutually corroborative. To recap: an impulsive, politically radical, and mentally unstable man with a history of violence committed an opportunistic murder, left incriminating evidence everywhere, and was immediately captured after fleeing the scene and shooting a police officer to evade arrest. Unless for some reason a person is committed, a priori, to Oswald’s exoneration, the official account of the Kennedy assassination is intelligible and, in light of the supporting evidence, unsurprising.

But then, surely Oswald must have conspired with someone else. Because—as we all know—the 8mm colour film of the assassination shot by Dallas dressmaker Abraham Zapruder conclusively proves more than one rifle. Discussing Oswald’s chances in Stone’s film, Garrison’s assistant Lou Ivon says that “the Zapruder film establishes three shots in 5.6 seconds … and Oswald was at best a medium shot.” The Zapruder film establishes nothing of the kind. The film was shot at 18.3 frames per second, so from the first shot (which Stone agrees was fired at frame 160) to the third and final shot at frame 312 is 8.3 seconds. Nor was Oswald a poor shot. In his indispensable investigation into the shooting, Case Closed, Gerald Posner writes that:

…at the Marine Corps recruit depot in San Diego … [Oswald was] trained in the use of the M-1 rifle. On December 21, 1956, after three weeks of training, he shot 212, two points over the score required for a “sharpshooter” qualification, the second highest in the Marine Corps. Such a score indicated that from the standing position, he could hit a ten-inch bull’s-eye, from a minimum of 200 yards, eight times out of ten.

Oswald was only 88 yards from Kennedy when he fired the fatal shot. Ivon also describes the Mannlicher-Carcano as “the world’s worst shoulder weapon,” which isn’t accurate either. Posner elaborates:

When the FBI ran Oswald’s gun through a series of rigorous shooting tests, it concluded “it is a very accurate weapon.” It had low kickback compared to other military rifles, which helped in rapid bolt-action firing. … The Carcano is rated an effective battle weapon, good at killing people, and as accurate as the U.S. Army’s M-14 rifle. … “The 6.5mm bullet, when fired, is like a flying drill,” says Art Pence, a competitions firearms expert. Some game hunters use the 6.5mm shell to bring down animals as large as elephants. The bullets manufactured for Oswald’s Carcano were made by Western Cartridge Company, and the FBI considered them “very accurate … [and] very dependable,” never having misfired in dozens of tests.

“The Zapruder film is the proof they didn’t count on, Lou,” Garrison tells his assistant. In fact, the Zapruder film disproves the conspiracy theorists’ two most powerful claims: that a single bullet could not account for seven wounds inflicted on Kennedy and Connally, and that the final shot came from the grassy knoll to the right-front of the limousine.

In the Beyond Conspiracy documentary, a 3D computer model of the footage, painstakingly constructed by computer animator Dale Myers, allows us to watch the assassination from any viewpoint in Dealey Plaza. Advancing the animation frame-by-frame, it is possible to identify the precise moment Connally is hit from the flip of his jacket lapel as the bullet passes through his body. Frame-by-frame analysis further establishes that the moment Kennedy is hit by the fatal shot, his head moves forward by 2.3 inches before his body convulses backwards due to a violent neuromuscular spasm (not unusual when the head and brain experience massive trauma), and the forward expulsion of blood and tissue as the top-right of the president’s head came apart. The entry wound in the back of Kennedy’s head established by the (repeatedly authenticated) autopsy photographs could not have been inflicted by a shot from the grassy knoll.

Watch for yourselves:

I found the computer simulation too convincing to dismiss. I knew that if this same technology had been used to demonstrate that the kill shot came from in front of the motorcade, I would have considered that evidence decisive and final. So what grounds did I have for rejecting a less welcome conclusion arrived at by the method? Well, none really. And with that, my belief fell apart.

III.

Having a foundational part of your worldview reduced to atoms in under an hour and a half is pretty destabilising. Over the subsequent weeks, it dawned on me how many assumptions had been carelessly built on that foundation and, consequently, how different and peculiar the world now looked. But it was also liberating. I suddenly found myself with much more room to think and, in the intervening years, my views about all sorts of things have changed in all sorts of ways.

So, returning to JFK in preparation for writing this essay was an odd experience. It remains an enjoyable and exciting film, but much of what I had found powerful or emotive in my teens and twenties now looks absurd. The problem is that once you accept Oswald did the shooting alone, what remains seems inconsequential and makes very little sense. Even as fortified by Stone, Jim Garrison’s case against Clay Shaw is a confused and incoherent mess. From what I can tell, it breaks down like this:

- New Orleans lawyer Dean Andrews claimed to have received a call on the day of the assassination from a man using the alias “Clay Bertrand,” who asked him to represent Lee Harvey Oswald. Andrews later retracted this claim, but told the Warren Commission he had previously helped Oswald try and get his marine discharge upgraded.

- Two days after the assassination, Garrison’s office received a tip that a man named David Ferrie had driven from New Orleans to Houston on the night of 22 November. The tipster was Jack Martin who worked for Guy Banister, a former FBI agent turned private eye, virulent anti-communist and racist, and generally reactionary headcase. Ferrie knew Banister. Martin hated Ferrie, and after the assassination he circulated the rumour that Ferrie also knew Oswald. “544 Camp Street” was stamped on some of the Fair Play for Cuba flyers Oswald was seen distributing in New Orleans in the Summer of ‘63, and Garrison claimed this address led to Banister’s office upstairs.

- Garrison developed the conviction that these two rather unpromising leads were somehow connected. He questioned Ferrie (who denied knowing Oswald), and then instructed his staff to find the mysterious “Clay Bertrand.” Garrison would later announce that “Clay Bertrand” was local businessman and director of the International Trade Mart, Clay Shaw. For some reason, Garrison found it significant that Shaw and Ferrie were both gay. Shaw denied knowing Ferrie or Banister or Oswald.

- A Ferrie-Shaw connection was belatedly provided by a 25-year-old insurance salesman named Perry Raymond Russo (who becomes male prostitute “Willie O’Keefe” in Stone’s film). Russo had been a friend of David Ferrie, and would later testify that he’d attended a party at his house at which Shaw (calling himself “Bertrand”) and a man with a bushy beard called “Leon Oswald” were present. After the party, Ferrie, Shaw, and “Oswald” incautiously discussed assassinating Kennedy using a “triangulation of crossfire.”

- A 29-year-old heroin addict named Vernon Bundy told Garrison that he had seen Oswald and Shaw together.

On this basis, Garrison arrested Clay Shaw on 1 March 1967 and charged that he “did wilfully and unlawfully conspire with David W. Ferrie, herein named but not charged and Lee Harvey Oswald, herein named but not charged, and others, not herein named, to murder John F. Kennedy.”

The problems with this case are many and various. But, for the sake of argument, let’s just accept that Garrison was right on all five counts—that Ferrie and Shaw and Oswald and Banister all knew one another; that Shaw used the alias “Bertrand”; and that Shaw, Ferrie, and Oswald all discussed assassinating Kennedy in front of Perry Russo. So what? The only person directly tied to the assassination is still Oswald, and Oswald was the person Garrison was trying to absolve! By charging Shaw with conspiring with Ferrie and Oswald to murder the president, Garrison had succeeded in tying Oswald’s guilt or innocence to Shaw’s.

This worried a number of Garrison’s staffers at the time. An eccentric English journalist named Tom Bethell worked for Garrison for a while as a researcher, and the diary he kept offers an illuminating account of a shambolic investigation. On 7 December 1967, Bethell wrote:

It cannot be stressed too strongly that proving Oswald innocent and proving Shaw guilty are antithetical aims. If Oswald is proven innocent, Shaw is virtually exonerated.

If Shaw is guilty of conspiracy, then Oswald must be either an actual assassin or have concurred in his own frame-up, by allowing his rifle to be taken into the TSBD [Texas School Book Depository] etc. Moreover, the argument that Oswald should have (a) discussed assassinating the President with Shaw and Ferrie, and (b) be innocent, when he was in the building from which the shots were fired, when his gun was also in the building, and when the bullet fragments ballistically matched to that gun were found in the car of the dead President, lacks plausibility to say the least.

In fact, nobody seems to have remarked on the fact that Russo’s testimony, if it is true, actually increases the likelihood that Oswald was an assassin, since, in addition to the prior evidence against him, he is now involved in a prior discussion about the assassination.

Bethell is writing this nine months after Clay Shaw’s arrest.

Stone’s film portrays Garrison as the steady leader of a loyal staff whose hard work and integrity are sabotaged by one treacherous member. The accounts of Bethell and others who had the sense to bail out bring to mind an operation more like that in the present White House. Garrison would rail against the FBI and denounce defectors in the press as CIA plants who had been people of no importance to his operation anyway. The remaining staff were a mixture of true believers and those privately colluding to thwart Garrison’s more excessive whims. Others realised the case was a disaster and hoped some unforeseen intervention would prevent it from ever reaching a courtroom.

Garrison was particularly proud of a code he had cracked/devised which allowed him to unscramble various numbers found in Lee Harvey Oswald’s notebooks. On 26 October 1967, Bethell recorded the following:

On Saturday (28th) Garrison talked to [British author and assassination theorist Michael Eddowes] in my office. Eddows [sic] was inordinately impressed by the ‘code.’ For me it was a bizarre experience. After going through the P.O. 19106 ‘code’, he branched out into several other variants supposedly employed by Oswald, eg a code which gives you the CIA phone number in New Orleans.

Garrison’s method of working this out is as follows: first he finds a series of digits or numbers in Oswald’s address book (several pages are filled with scrawled figures, so there is plenty of choice) and selects a group which strikes his fancy as being encoded. He then looks up the CIA phone number in the phone book. Then, using an arbitrary method which is uniquely suited for that purpose, he translates one set of digits into the other. He also did this with the FBI phone number, but needless to say he had to use a different decoding procedure. Of course, this is not quite the way he explains it. He starts out by showing you the digits in Oswald’s book, and persuades you that it is in code. Then comes the decoding ‘key,’ which he makes sound as plausible, logical and as easy to remember as he can, (Garrison can be surprisingly persuasive on occasions like this.) Using the key, he translates the digits into a different set, and writes out the new number for you. Then, with the air of a conjuror arriving at the climax of his trick, he opens the phone book and shows you the CIA phone number. The same number!

Eddows seemed to be completely hoodwinked by this, and was tremendously impressed by the whole performance. Garrison had complete confidence in Eddows after this, and even let him keep the sheets of legal paper he had been demonstrating the variants of the code on, which I should have thought could almost have been regarded as an incriminating document of some kind. Garrison also let Eddows take away a copy of Clay Shaw’s address book.

Conspiracy researchers like Eddowes, Vincent Salandria, and Mark Lane drifted in and out of the office at will, xeroxing documents (with Garrison’s permission), and offering advice that Garrison’s more prudent staffers would then have to talk him out of. From insider accounts, the whole operation sounds desperate, disorganised, inept, poorly resourced, strategically confused, and totally unethical.

But while his staff chased down deadbeat leads and fretted that their case made no sense, Garrison was publicly predicting a devastating victory at trial and announcing that he had completely solved the mystery. When confronted with the failings of his investigation, he proved extremely hard to embarrass. In Stone’s film, Garrison and his wife watch Stone’s reconstruction of an NBC-TV documentary broadcast after Shaw’s arrest, in which the presenter says, “A team of reporters has learned that District Attorney Jim Garrison and his staff have intimidated, bribed, and even drugged witnesses in their attempt to prove a conspiracy involving New Orleans businessman, Clay Shaw in the murder of John F. Kennedy.” Because we never see Garrison do any of these things, we are expected to conclude that these allegations are lies.

But Garrison had drugged at least one witness, and he defended doing so in the same NBC-TV documentary he and his wife are shown watching. Perry Russo began speaking to the Baton Rouge press shortly after the death of David Ferrie. At that point, and on 25 February when he was first interviewed by Garrison’s assistant Andrew Sciambra, he made no mention of a party, “Clay Bertrand,” or a plot. He had already told WDSU TV that he had never heard of Oswald before the assassination. On 27 February, Russo met with Garrison’s investigators at Mercy hospital, where he was administered sodium pentothal and re-interviewed. Now, his story began to change. At least two further interviews were conducted under hypnosis (on 1 March, the day Shaw was arrested, and again on 12 March), during which Russo was directed with highly leading questions and fed important information he had never volunteered. Asked about all this by a BBC Panorama journalist, Garrison replied:

We decided to give [Russo] objectifying, uh, machinery to make sure he was telling the truth. We gave him the truth serum [sodium pentothal] in order to make sure. Now, it seems to me that this is a rather unusual prosecution… uh prosecuting office which has a pretty good case making its witness take objectifying tests to make sure they are telling the truth. We did it for this reason. We used hypnosis for the same thing. Just to make sure he was telling the truth.

Although Garrison would later deny it (just one of a litany of lies), Russo also took a lie detector test which the administrator reported showed “deception” and evidence of a “psychopathic personality.” Vernon Bundy, the drug addict who claimed to have seen Oswald and Shaw together, also failed a polygraph and confessed to two witnesses that he was lying in the hope of getting his parole violations quashed. In an act of grotesque irresponsibility, Garrison called both Russo and Bundy to the stand as witnesses against Clay Shaw anyway. That he felt he had to do so is an indication of the meagre pool of testimony at his disposal.

Bill Broussard, a composite of various Garrison staffers, is allotted the role of villain in Stone’s film after an FBI agent convinces him to turn on the investigation. But in view of the above, he sounds like the lone voice of reason during his final confrontation with Garrison:

Broussard: You tell me how the hell you gonna keep a conspiracy going on between the mob, the CIA, the FBI, and army intelligence, and who the hell knows what else when you know for a fact we can’t even keep a secret in this room between twelve people. We got leaks everywhere. I mean, we are going to trial here y’all and what the hell do we really got? Oswald, Ruby, Banister, Ferrie are dead. Shaw? I mean, maybe he’s an agent I don’t know. But as a covert operator in my book he is wide open to blackmail because of his homosexuality.

Garrison: Shaw’s our toehold, Bill. Now I don’t know exactly what he is or where he fits in and I don’t really care. I do know he’s lying through his teeth and I’m not going to let go of him.

Broussard: And for those reasons you’re gonna go to trial against Clay Shaw, chief? Well, you’re gonna lose.

And lose he did. On 1 March 1969, exactly two years after he was arrested, Clay Shaw was cleared by the jury in less than an hour. Garrison was not in court for the verdict.

IV.

By the time the trial ended, many of the old guard of conspiracy researchers had wearied of Garrison. But Oliver Stone’s JFK provided him with a new generation of defenders. In Stone’s black-is-white looking-glass reality, Jim Garrison is James Stewart, Lee Harvey Oswald is Josef K., and the man Garrison pointlessly persecuted is a homicidal Sadean libertine. Stone even contrived to ennoble the uselessness of Garrison’s case, by inviting us to find something honourable in his humiliation by impossible odds. But those odds were the product of Garrison’s own recklessness—he had used the power of his office to hound an innocent man with nothing but speculation and innuendo. Seen from outside the conspiracy bubble, even Costner’s whitewashed version of Garrison cuts a diminished figure—obstinate, self-righteous, self-pitying, ridiculous, and wrong.

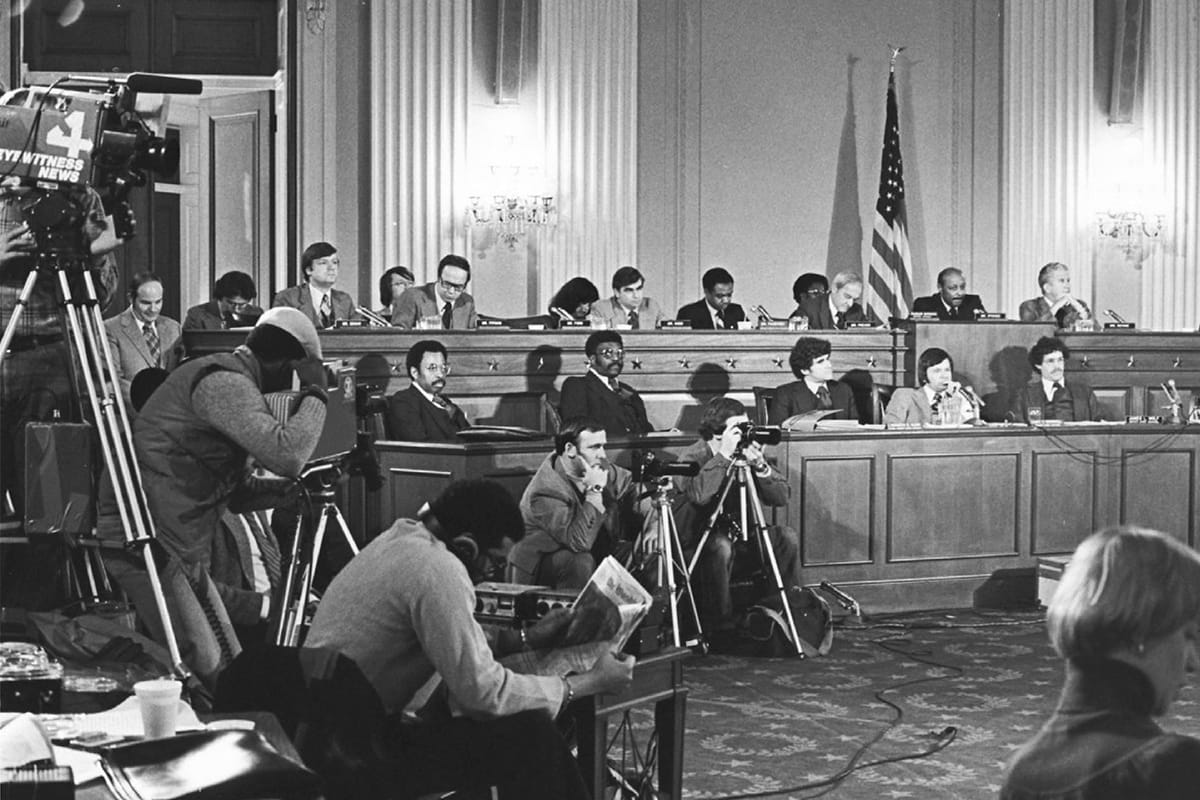

Garrison’s misbegotten prosecution arguably made at least a minor contribution to the formation of the House Select Committee on Assassinations in 1976. Tasked with re-investigating the murders of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, the committee conducted an exhaustive review of all the evidence and a whole new battery of tests using state-of-the-art technology. At the end of his film, Oliver Stone informs his audience that “A Congressional Investigation from 1976–1979 found a ‘probable conspiracy’ in the assassination of John F. Kennedy and recommended the Justice Department investigate further.”

This is one of Stone’s more truthful assertions, but it is still highly misleading. The Committee did indeed conclude (incorrectly) that there had been at least four shots and two rifles in Dealey Plaza on 22 November 1963. But they also concluded that (a) the shot from the grassy knoll (fired by persons unknown) had missed the car completely and that (b) Lee Harvey Oswald had fired the other three. This second conclusion was supported by a new mountain of evidence. In his thoroughly enjoyable new book I Was a Teenage JFK Conspiracy Freak, Fred Litwin spends four pages discussing the HSCA’s scientific findings, and provides summaries of the forensic pathology and photographic panels, the expert earwitness analysis, the handwriting and fingerprint authentication, the Mannlicher-Carcano firing tests, and the report of the firearms panel, all of which pointed to Oswald’s guilt.

So the notice at the end of Stone’s film might more accurately have read, “The findings of a Congressional Investigation from 1976–1979 conclusively discredited everything you have just seen.” Instead, he ignored them. The conspiracy researchers had been provided with every scientific test they had ever demanded and it made no difference. All that time, money, and expertise spent re-establishing what had already been established, and for what? “Reading the actual evidence was a revelation,” Litwin writes. “[But] you’d be hard-pressed to find acknowledgement, positive or negative, of what the HSCA was able to accomplish in any conspiracy book.” And why? Because conspiracy theories offer no freedom of thought for the independently minded, only the prison of motivated reasoning.

In 1963, the assassination of the president by a communist misfit was an embarrassment to the New Left and an unexpected boon to their hated antagonists on the anti-communist Right. Consequently, revisionists were afforded generous space in radical publications like Ramparts to implicate their enemies and exonerate anyone to whom they were ideologically sympathetic. “It seems to me,” William Buckley drily remarked during his 1966 Firing Line interview with Mark Lane, “that it would just be absolutely divine if it could be proved that Mr. Oswald was subsidised by [oil tycoon and Republican activist] H.L. Hunt, and the John Birch Society, the Minutemen, given a little moral support by National Review, [and] that [Republican senator Barry] Goldwater cleared it. That would be sort of the ne plus ultra in causing delight in many quarters of the United States.”

The paranoia and political disgrace of the 1970s provided theories of government corruption and conspiracy with fresh plausibility and seductively expedient new reasons to embrace them. In his 2009 examination of conspiracy thinking, Voodoo Histories, British journalist David Aaronovitch remarks that, “For sections of the Left, of course, looking back on how the promise of the Vietnam protests became first the Nixon years and then the Reagan era, had an interest in creating an account which somehow mitigated any sense of their own failure, or the failure of their ideas.” For many others, however, the idea that Kennedy had been murdered in a plot simply restored a sense of cosmic order that had been disturbed by an act of arbitrary violence. “I know that millions and millions of people in this country believe there was a conspiracy,” says American historian and Kennedy biographer Robert Dallek in Beyond Conspiracy, “because I think it is very difficult for them to accept the idea that someone as inconsequential as Oswald could have killed someone as consequential as Kennedy.”

As for Oliver Stone, had he actually cared about the integrity of the Garrison investigation, he might have noticed that it was full of holes. But he was swept up in the romanticism of Garrison’s lonely doomed crusade, and wanted so badly to believe the assassination finally explained the insanity of Vietnam. His film, however, explains nothing. Conspiracy theories foreclose the possibility of explanation, because they postulate unalterable conclusions in search of evidence instead of following evidence to plausible conclusions. And for that reason, no countervailing argument, hypothesis, or fact will ever be enough to dissuade committed theorists. But there comes a point when those who insist most strenuously on the paramount importance of the truth have to be honest with themselves. Pace Jim Garrison, the world makes a lot more sense when examined from the correct side of the looking-glass, where black is black and white is white, and things are more or less as they appear to be.

Given what we know about the world, what would we expect to find in the wake of the assassination had Oswald acted alone? We would expect to find a convergence of evidence pointing to his guilt and a paucity of evidence pointing elsewhere. And since that is exactly what we do find, what is the more parsimonious explanation? That all the evidence implicating Lee Harvey Oswald was doctored or planted? And that all witnesses were bought off and intimidated or killed? And that a plot and cover-up requiring hundreds of conspirators never yielded a single confession? And that every other shooter in Dealey Plaza simply vanished into thin air? Or perhaps it would be more reasonable to conclude that the conspiracy theorists are simply wrong.

Further info:

- The Beyond Conspiracy documentary can be seen here.

- NBC-TV 1967 documentary The JFK Conspiracy—The Garrison Investigation can be seen here. Garrison’s reply can be seen here.

- William F. Buckley’s Firing Line interview with Mark Lane can be seen here.

- An extract from Fred Litwin’s book I Was A JFK Conspiracy Freak was published in Quillette here.

- Craig Colgan’s 2017 Quillette essay on the slow death of JFK conspiracy theories can be found here.

- For the really committed, David von Pien has collected all 23 parts of Lee Harvey Oswald’s 1986 mock trial into a YouTube playlist here. Gerry Spence appears for the defence and Vincent Bugliosi prosecutes.

- There are a number of good sites online debunking the JFK conspiracy theories, but John McAdams’s endlessly fascinating resource is probably the best. Hours of fun here.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Oswald was charged with murdering the president. He was in fact booked for the crime but not charged before he was murdered by Ruby.