Activism

Single Issue Campaigning and the Polarisation Problem

Campaigns that mischaracterise issues and stigmatise opponents reduce the complex to the simplistic in ways that are fundamentally unhelpful

In their new book, The Coddling of the American Mind, Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff argue that a polarisation cycle exists at US universities. First, a progressive professor does or says something provocative in response to a real or perceived injustice caused by conservatives. Next, the right-wing press picks up the story, and it is shared and retold to amplify conservative outrage. Then, people are encouraged to email or tweet at academics. Finally, the university, which isn’t used to being attacked, makes a badly thought-through decision in order to make the problem go away, which too often means that someone leaves an institution when they probably shouldn’t.

As progressive campaigners working outside of college campuses, the cycle Haidt and Lukianoff describe felt worryingly familiar. We began to wonder whether well-intentioned progressive campaigns were contributing to the same kind of polarisation in wider society. Polarisation is one of the few remaining political topics upon which there seems to be something approaching a consensus. There is widespread agreement that our political identities increasingly preclude us from listening to our opponents. Consider the following:

- 85 percent of people in the UK, and 84 percent in the US, think their country is divided. A significant majority of these believe that it’s worse than a decade ago.

- People are more likely to be deeply concerned by criminal actions of political opponents than those they agree with.

- 55 percent of strong liberals say a vote for Trump would strain a friendship. Yet this does not appear to be true in reverse; Trump supporters say they are willing to be friends with liberals.

- There has been a 21 point increase in the distance between Republicans and Democrats on policy issues.

The last 15 years have seen a progressive campaigning explosion. More than three million people are active on the British progressive campaigning site 38 Degrees. Around the world, almost 50 million are active with Avaaz. Numerous NGOs have run petitions and online campaigns on their own websites or hosted by these organisations. We have worked on many such campaigns, and movements like these focus on ambitious and often worthy goals. But it takes years to persuade governments to change legislation. Regulators and businesses can be slow to enact meaningful change. So, in the short run, it’s natural to focus on securing quick and comparatively easy wins. These are mainly small campaigning actions designed to keep up the pressure on legislators and related interests.

Social media and email enable millions of new people to involve themselves in campaigning with a couple of mouse clicks. Previously, they had to join organisations, receive magazines and other literature by post, and handwrite letters. Now everyone can be alerted by email or social media. This has made the dissemination of information and the solicitation of support much easier. On the other hand, measuring progress and success in clicks and shares encourages the simplification of complex issues in order to maximise outrage. Campaigners want to provoke an emotional response because it helps build return visits and pushes people up the “ladder of engagement.” This technique is standard campaigning procedure designed to get people more involved, and it should be readily recognisable from your email inbox and social media feeds.

The message tends to be that a serious and urgent crisis is being caused by bad people—people who, faced with a simple moral choice, have decided to choose the obviously immoral option (usually for reasons of greed or self-interest). Sign a petition, and it will force the hand of those in power to enact the necessary changes and do the right thing. To build support and momentum you’ll then be asked to share your petition on Facebook or Twitter. We are all predisposed to believe what our friends tell us, so sharing a petition helps build credibility and cement a negative view of whoever or whatever has been identified as the antagonist.

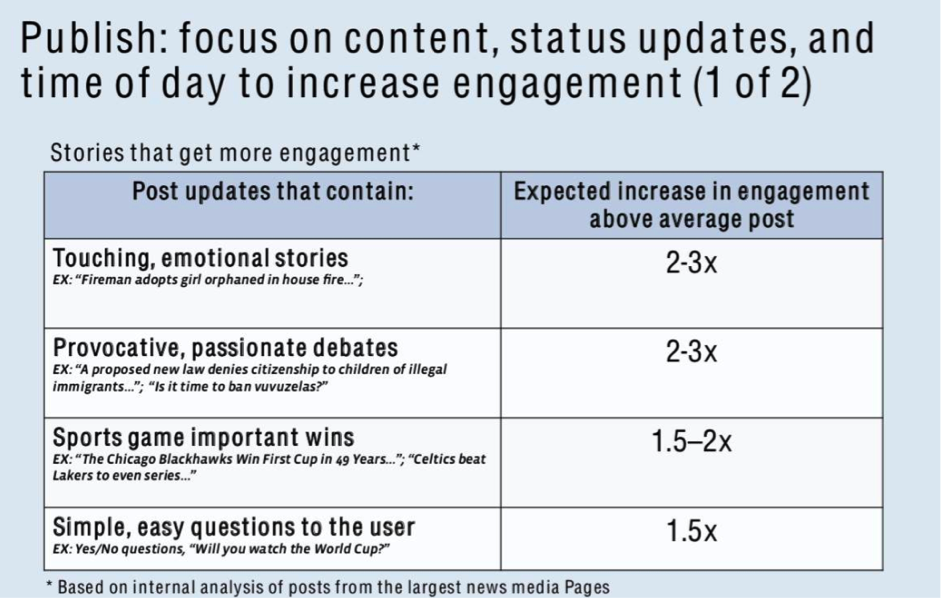

These shares are automatically accompanied by text typically designed to provoke, since Facebook’s own data suggest that provocative posts are two-to-three times more likely to secure engagement. The following table was shared with us by a senior social media strategist who has worked for media companies and global PR and brand consultancies on both sides of the Atlantic:

There are numerous ways of ramping up outrage among potential supporters. Highlighting a piece of stupidity from a prominent opponent of the cause, for example, or alleging that a piece of helpful research is being suppressed by its critics. The internet has made it very easy to find and publicise obnoxious opinions as well as simply incorrect ones. People are then asked to promote these obnoxious stupidities (which are mischaracterised as representative) through their social network, bringing yet more people in to sign the petition by stoking further indignation and outrage.

Having signed and shared a petition, and persuaded their friends to come on board, supporters will now be encouraged to perceive this as “their” campaign. At this point, those most deeply engaged will be asked to increase their commitment by, for instance, writing to or calling their constituency politician. This, they will be told, is necessary to overcome subsequent hurdles.

Finally, there will be a victory of some description, for campaigners and supporters alike. It will be announced that the signatures and shares on social media made all the difference, reinforcing the belief among supporters and their networks that all this clicktivist action was consequential and worthwhile. This deepens the perception that the forces of good have triumphed in some small way over the forces of evil, but since much remains to be done, supporters will be encouraged to repeat this cycle all over again.

In many respects, this kind of engagement is good for democracy. Many more people have the opportunity to participate and campaign, and to involve themselves in important decisions. Campaigns can bring people together too. We’ve seen campaigns, initially sparked by the circulation of an online petition, which have succeeded in uniting people who would normally never meet. We’re proud to have been involved in campaigns like these, and sometimes they do have unambiguously beneficial effects, from getting women on bank notes to making medicinal cannabis available on prescription.

But this kind of campaigning is also worsening polarisation in our society. The division of the world into good and bad people may help to solicit immediate support, but it rarely reflects reality. As any reader of Jonathan Haidt’s previous work will confirm, people and organisations are rarely wholly good or bad.

Pharmaceutical companies are neither heroic nor malevolent. Like many institutions and the people who work in them, they can be either, depending on context. Yes, inflated drug prices in America are outrageously high. But the same companies sell the same drugs to other countries far more cheaply, because those countries negotiate harder and regulate more effectively. And these companies research and produce the vaccines that save millions of lives every year. Those who see drug companies as simply baleful make themselves vulnerable to conspiracies about ‘Big Pharma’ and vaccination myths.

The kind of paranoid conspiracism encouraged by black and white thinking also risks blaming a campaign’s failure on sinister forces. But sometimes campaigners lose because they haven’t won the argument or because they haven’t run a good enough campaign. Blaming a conspiracy of powerful interests for defeat necessarily precludes an honest conversation about mistakes, and the opportunity to learn from them.

Furthermore, if we persuade ourselves and our supporters that opponents are simply bad people with immoral motives, it should be unsurprising if we no longer want to spend time with them, or with people who vote for them. After all, why should anyone want to spend time with those indifferent to the harm they inflict on others? What reason does anyone have to listen to their point of view? If someone is persuaded that all conservatives are selfish and evil and that they despise the poor and unfortunate, how can that person be expected to react if a new neighbour were put a poster in their window supporting the Tories? And if you were to find yourself denounced as a “deplorable” or personally blamed for systemic failure, would that make you more likely to listen to your critics and opponents? Or would you dig in, defensive and defiant?

Campaigns that mischaracterise issues and stigmatise opponents reduce the complex to the simplistic in ways that are fundamentally unhelpful—they polarise society, inflame passions, and do little to fix the problems they identify and ostensibly seek to solve. In the end, repairing a broken social care system in the UK or bringing down rates of criminal recidivism in the US will require cross-party agreement on complicated social and policy solutions. But, because it is easier to mobilise people against individuals, entrenched problems remain unaddressed. Yes, we can (and should) punish corrupt and incompetent bankers. But until we agree upon the systemic causes of the 2008 crash, we’re at risk of another.

In their book, Haidt and Lukianoff offer an outline for how we might begin to address the polarisation on American campuses. We have adapted it in the hope that it can be used to encourage moderation in political campaigning:

- Measure the impact of progressive campaigning on polarisation.

- Expand the progressive playbook to help people help themselves. Tools offered by organisations such as Money Saving Expert and Which? are great examples of this.

- Recognise that if your are running repeated campaigns against the same mainstream targets it may cause them to entrench. Remember that the most robust campaigns often get broad political support, as the campaign to increase UK aid has.

- Acknowledge that, on most topics, shifting public opinion will involve reaching across the political aisle, from opinion leaders to the grassroots. Celebrate opponents joining your cause. If you are fighting Trump in America then moderate Republicans who vote against him are crucial to your winning coalition. If you are fighting for abortion rights, seek out persuadable Catholic priests. And when you secure their support, treat them as partners, not as subordinate “allies” whose job is to do as they are told. They will have insight and knowledge you do not.

- Actively seek out conversations with those who disagree with you. And be as open to changing your mind as you would like them to be to changing theirs.

If we ignore this advice and continue to prioritise the ruthless pursuit of short-term goals at the expense of good faith debate and understanding, then the long-term exacerbation of our current divisions will constitute a net loss for us all.

Rob Blackie is a digital strategist who has worked with a wide range of ngo, government and corporate campaigns. You can follow him on Twitter @robblackie_oo

Ali Goldsworthy is founder of The Depolarization Project, a former political advisor and senior staffer in a number of campaigning organizations. You can follow her on Twitter @aligoldsworthy