Education

Western Civilisation "Not Welcome Here"

The new humanities maintain that for the last 500 years, Western Civilisation has got it wrong when it comes to knowledge, truth and science.

In 2017, following the wishes of the late Paul Ramsay, a businessman and philanthropist who made his fortune in the healthcare industry, the Ramsay Centre for Western Civilisation was set up in Australia. Paul Ramsay was deeply concerned that Australians are not being taught about Western Civilisation either at school or university. So he left part of his $3.4 billion fortune so that something would be done about it. As the Director of the Foundations of Western Civilisation Program at the Institute of Public Affairs, I have been keeping a close watch on developments.

The Ramsay Centre has devised a Bachelor of Arts in Western Civilisation based on great books and works of art, to be taught in partnership with universities. Since its launch however, the Ramsay Centre has encountered almost nothing but open hostility and resentment from potential university partners.

At the University of Sydney, staff some months ago launched a ‘Keep Ramsay out of USYD’ petition. The same staff are currently having conniptions because their Vice–Chancellor has now announced that he’ll consider taking the Centre’s $64 million grant if it gives the university complete control over the curriculum, the reading list, and the academic appointments involved with the Bachelor of Western Civilisation.

Prior to this, the Australian National University pulled out of negotiations at the 11th hour when its Vice-Chancellor cited concerns about academic autonomy following a very public and acrimonious pushback against the program from several ANU academics and the Tertiary Education Union.

* * *

A few weeks ago, I was invited to attend a University of St Andrews alumni drinks in Melbourne. The evening began promisingly enough. A smart bar hotel bar, eight individuals of various ages and occupations, gathered together with the prospect of a pleasant evening of reminiscing ahead. Amid the usual exchange of pleasantries, I discovered that my one of my fellow attendees was a senior university administrator. When he learnt that I am currently the Director of the Foundations of Western Civilisation at the Institute of Public Affairs, I detected a slight look of discomfort. Any bonhomie that might have existed at the commencement of the evening vanished as soon as he asked me what I thought about the Ramsay Centre for Western Civilisation.

The rejection of a Bachelor of Arts in Western Civilisation is predicated on the absurd notion that anyone who wants to talk about or study Western Civilisation must be a white supremacist. In some academic circles, Western Civilisation is held responsible for all evils in the world, past, present and future.

Earlier this year, the Dean of Arts at Newcastle University wrote a piece for The Conversation in which she stated that Western Civilisation is past its used by date and that it’s too ‘white’ to teach in multi-cultural classrooms. The University of Sydney academics leading the charge, claim that the BA will “pedal racism disguised as appreciation for ‘Western Culture.’” At a National Tertiary Education Union forum, former University of Sydney chair, sociologist and gender theorist Raewyn Connell, told her audience that the curriculum “has racism embedded in its agenda.”

When I articulated to my fellow alumnus that I had not been surprised at the response from Australian universities—given the antipathy displayed towards Western Civilisation by many academics—he did not think this hostility to be a bad thing. When I added that I thought all students studying an undergraduate degree in history, or any humanities degree for that matter, should be required to do a foundation course in Western Civilisation, he was shocked and horrified. From his point of view, knowing about what happened during the Scientific Revolution or the Enlightenment is an irrelevancy and a waste of students’ time. For him, history is about ‘issues,’ not knowledge.

It was at this point that I realised that just how far universities, especially the humanities departments, have strayed from their original purpose. From the Renaissance until the 1960s, the humanities, derived from the expression ‘studia humanitatis’ or the study of humanity, made it their purpose to make sense of and understand the world through the great traditions of art, culture and philosophy. There appeared in the 1970s and 1980s however, a range of ‘new humanities’ subjects which rejected this tradition. The new humanities were underpinned by a range of radical post-structuralism and post-modernist theories which had been conjured up in the previous decade by a predominantly French group of philosophers such as Jacques Derrida, Louis Althusser, Michel Foucault, as well as the psychiatrist, Jacques Lacan.

The new humanities maintain that for the last 500 years, Western Civilisation has got it wrong when it comes to knowledge, truth and science. These fields tend to claim that both knowledge and truth are not absolute, but are relative. For example, there is no objective truth and truth is dependent on who is speaking it and in what context. Insofar as science is concerned, they claim that scientific theories don’t really provide us with what we could call knowledge but are actually “invented” rather than discovered.

History as a discipline best exemplifies the influence of the postmodernists and their ilk on the humanities. Many historians have enthusiastically embraced the idea that truth is no longer within the historian’s grasp and that it’s impossible to use history to add to knowledge about humankind. This is the kind of thing which would normally signal the death knell for any discipline, but historians have risen from the ashes and have forged for themselves a new purpose—the attainment of social justice.

This is not social justice in the Enlightenment sense, which meant equality before the law and equal rights, but social justice in the activist sense, where the ultimate goal is to achieve perfect equality by destroying ‘oppressive’ institutions and rearranging society. The historians’ new role is to tell the inequality narrative of the oppressed and the oppressor through the lens of class, gender, and race. Matthew A. Sears, associate professor of classics and ancient history at the University of New Brunswick believes that ancient Greek sculptures epitomise racism and white supremacy, and that history is “about politics,” it’s main purpose being to “better understand the human condition and shed light on questions of contemporary relevance.”

Partisans assail historians for judging the past by today’s standards. Here’s why they’re wrong—Even by the standards of their day, many heroes of Western civilization engaged in immoral acts, by @matthewasears and via @washingtonpost @madebyhistoryhttps://t.co/WJoRYMhG6J

— GreekHistory Podcast (@greekhistorypod) July 13, 2018

This approach has its origins in the nineteenth century, when Georg Hegel constructed his worldview of history into a narrative about stages of human freedom. His was the view that history was simply the process of moving towards the realisation of such freedom. Later that century, Karl Marx’s built on Hegel’s new paradigm with his theory of historical materialism, proposing that society’s productive capacity and social relations of production determined both its organisation and development.

Both Hegel and Marx essentially denied the role of individual human agency, treating the past as the product of inexorable forces and trends which were primarily of a material and economic nature. “Society” wrote Marx, “does not consist of individuals, but expresses the sum of interrelations, the relations within which these individuals stand.’’

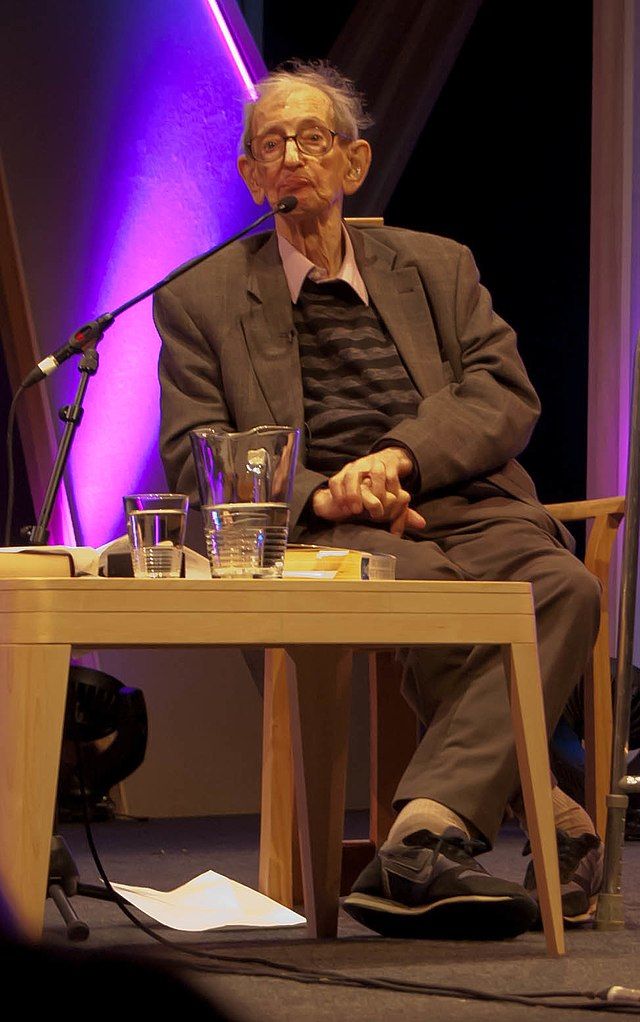

Karl Marx essentially created the template of identity politics for the study of history with his notion that human society is in a constant state of struggle and a zero-sum contest for power. In the 1960s, his model was adopted by British historian Eric Hobsbawm who deliberately re-wrote the history of the “long 19th century” as being a century of class struggle. Hobsbawm successfully transformed history as an academic discipline into a vehicle for social policy.

Since the 1970s, historians have embraced Marx’s template and applied it to their own particular historical fields, re-writing the past from the point of view of class, gender, and race. These new histories have gradually replaced the traditional canon of historical subjects which once upon a time formed the basis of an undergraduate degree in history in Australia.

In 2017, a study of all 746 history subjects taught in Australian universities revealed that 244 of those subjects were devoted entirely to class, gender, and race. Many were a pastiche of identity politics in which the stunning complexity of the past is increasingly reduced to a very limited range of themes. Students at Melbourne university can take ‘A History of Sexualities’ in which they discuss “how the gendered body and sex have been simultaneously linked to social liberation and control.” At the Australian National University, students can consider “the concept of ‘race’ within the contexts of the development of scientific knowledge in ‘Human Variations and Racism in Western Culture, c. 1450-1950.” A keyword search of all the history subject descriptions taught in 2017 reveals that there were more instances of the words gender and race than there are Enlightenment or Reformation.

What is more, a perusal of the University of Sydney’s history faculty staff profiles reveals that 20 of the 32 staff have variously identified gender and sexuality, racial thought, women’s history and power as their current historical fixations. The left-wing leitmotifs of class, race, and gender have replaced the essential core subjects which explain the political, intellectual, social and material basis of the history of Western Civilisation.

This approach is not only boring and repetitive, it is fundamentally anti-intellectual. Students in Australia are not being given a “positive formation” by their universities, which is exactly what the Ramsay Centre is attempting to rectify. Instead, they are being taught a narrow, one-dimensional view of the world seen through the prism of identity, over a curious and inquiring three-dimensional view of the world which opens the mind.

Students studying the humanities are not only finishing their degrees with a distorted view of the world in which the past is viewed as a contest between the oppressors and the oppressed, but they are imposing this particular worldview on society as they find employment in schools, government, and the corporate world. These days, for example, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to work out where gender departments finish and governmental departments or the corporate world begin, so blurred are the lines between them.

Since the 1960s, universities have been leading their students fairly and squarely down a path of un-education, unlearning and enlightenment, and they should be called to account. Now these students, filled with an ideological fervor and driven by social justice, are leading the rest of society down the same path, whether society wants it or not.