Books

Banned Books Week: 10 Pop Fictions to Annoy the Politically Correct

These are the books you should read with great ostentation at sidewalk bistros, corner restaurants, and in doctors’ waiting rooms.

Banned Books week is upon us again. Traditionally, this is a week during which liberals congratulate themselves for resisting concerned parents who wish to have controversial books pulled from school libraries and/or curricula. These tend to be books that support a liberal or progressive worldview. Last year’s list of the most banned books included Sherman Alexie’s The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian (challenged by some parents because of sexually explicit material), Jay Asher’s Thirteen Reasons Why (frank discussion of teenage suicide), Raina Telgemeier’s Drama (inclusion of LGBT characters), Khaled Hosseini’s The Kite Runner (sexual violence and promotion of Islam), Alex Gino’s George (inclusion of a transgender character), and so forth. Books that support a conservative worldview (Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged, Glenn Beck’s The Overton Window, William F. Buckley’s The Red Hunter, anything by Tom Clancy) are rarely pulled from school curricula because they rarely make it into the curricula in the first place.

My modest proposal for this year’s Banned Books Week is that we all spend a little time out in public reading books that are never likely to be included in your typical American high school’s curriculum. If you enjoy annoying the politically correct members of the illiberal Left (and what right-thinking American doesn’t?), these are the books you should carry with you on buses, trains, planes, and subways. These are the books you should read with great ostentation at sidewalk bistros, corner restaurants, and in doctors’ waiting rooms.

* * *

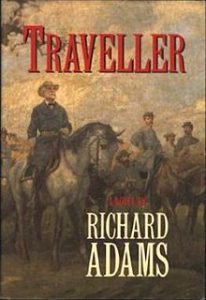

TRAVELLER by Richard Adams: All over the American south and elsewhere statues of famous Confederate leaders are being pulled down, sometimes lawfully by public consent, and sometimes unlawfully by people practicing civil disobedience. We shouldn’t lionize Confederate soldiers. They were fighting to keep African-Americans in chains. But nor should they be erased from our history. Robert E. Lee was one of the most fascinating Americans who ever lived. He was both a patriot who worshipped George Washington, and a traitor who tried to tear his own country apart. Traveller is a novel narrated by Lee’s horse. Progressives are likely to be offended by the notion of Lee’s life story as the stuff of popular romance. And the thought of that story being related via the somewhat comic device of a Mr. Ed-style narrator is likely to be seen as insensitive to all the genuine suffering Lee and his ilk perpetuated. But Adams’s novel is not a blind paean to Lee. It’s actually a very sneaky anti-war statement, in the same vein as Stephen Crane’s poem “War is Kind.” Because he has a limited understanding of human language, when Traveller hears southerners whooping and cheering about “going to war,” he believes that War is a place, a destination somewhere up North where everything will be wonderful and glorious. When he finds himself surrounded by humans who are killing each other in large numbers, he asks a veteran warhorse why they would do such a thing. The response: “You might’s well ask me why the sun goes acrost the sky. It’s what they do, like flies bite. They always have and they always will.”

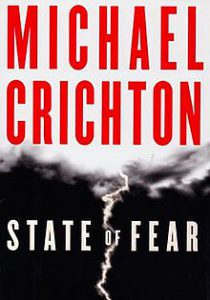

STATE OF FEAR by Michael Crichton: Climate science has not been especially kind to this techno-thriller, which waves away the notion that humans might be responsible for global warming. Nine of the ten hottest years on record have occurred since this book was published in 2004. Crichton didn’t live to see most of those years. He died in 2008 of lymphoma. Though he was a doctor/scientist, Crichton frequently ignored the scientific consensus, which may account for the fact that he maintained a smoking habit of several packs of cigarettes a day for most of his adult life. But good solid science has never been the best reason for reading a Crichton novel. As Stephen King put it: “A Crichton book was a headlong experience driven by a man who was both a natural storyteller and fiendishly clever when it came to verisimilitude; he made you believe that cloning dinosaurs wasn’t just over the horizon but possible tomorrow. Maybe today.” So go ahead and enjoy this exciting thriller. Just don’t quote from it when debating climate change with your liberal Prius-driving neighbor.

THE EDUCATION OF LITTLE TREE by Forrest Carter: For years this book was quite popular among school librarians. It tells the story of a boy who is orphaned at five and goes to live with his Cherokee grandparents, who instill in him a love of the land and of his Native American ancestors and their ways. Originally published in 1976 as a memoir, the book was reclassified as fiction in 1991 because of evidence produced by scholars that Carter had made up most of the story. Oprah Winfrey once recommended the book on her website. She pulled the recommendation when it was revealed that Forrest Carter was actually Asa Earl Carter, a notorious racist and one-time leader of the Ku Klux Klan. Carter’s racism can’t be excused as George Washington’s and Thomas Jefferson’s racism often is by saying, “His racial attitudes were typical of the time.” Even for his time (1925-1979) Carter’s racism was horrifying. He was once a speechwriter for Alabama’s white-supremacist Governor George Wallace. But even Wallace, amazingly, found him too much and got rid of him. It should be noted that Carter’s nastiness wasn’t just directed at African-Americans. He once shot two of his fellow Klansmen in a dispute over money. All of which makes it even more amazing that he produced such a beautifully written novel that is a hymn to the idea that mankind should live in harmony with the natural world and the spirit world. It also contains many beautiful observations on language itself. Consider the scene in which a peddler named Mr. Wine explains to Little Tree the difference between ‘stingy’ and ‘thrifty’:

[Mr. Wine said i]f you was stingy, you was as bad as some big shots which worshipped money and you would not use your money for what you had ought. He said if you was that way then money was your god, and no good would come of the whole thing.

He said if you was thrifty, you used your money for what you had ought but you was not loose with it. Mr. Wine said that one habit led to another habit, and if they was bad habits, it would give you a bad character. If you was loose with your money, then you would get loose with your time, loose with your thinking and practical everything else. If a whole people got loose, then politicians seen they could get control. They would take over loose people and before long you had a dictator. Mr. Wine said no thrifty people was ever taken over by a dictator. Which is right.

To his dying day, Paul Robeson never denounced his devotion to Stalinism, but that is no reason for us to stop listening to his records. Stalinist or not, he was a great singer. Likewise, Carter’s racism is no reason for us to eschew his fiction. And it reached its pinnacle in The Education of Little Tree. The progressive sitting next to you on the long flight to Chicago may furrow his brow, but go ahead and read this book. It is proof that even in the most benighted of souls a little light sometimes penetrates.

HANTA YO by Ruth Beebe Hill: According to Michael Korda’s Making The List: A Cultural History of the American Bestseller, 1900-1999, Hanta Yo was the 15th bestselling novel of 1979. It was generally well-received by critics. A reviewer for the Harvard Crimson called it “the best researched novel yet written about an American Indian tribe.” The positive reception didn’t last long. Shortly after the book’s publication, Sioux activists took umbrage at its portrayal of Plains Indian life and, according to an article in People magazine, “tried to force the work out of bookstores and libraries.” Ironically, one of the protestors’ objections back in 1979 was that the book portrayed homosexuality as if it were a natural part of Indian life. Nowadays that might be a selling point for the politically-correct. The author spent nearly 30 years researching this 1100-page tome. She interviewed more than 700 Native Americans during the course of her research, one of whom, Chunksa Yuha, lived with her and her husband and acted as her technical advisor for 15 years. The back of the book contains an extensive glossary of Lakota Sioux words, and a separate compendium of the tribe’s idiomatic phrases. The book has been out of print for years, but it deserves a rediscovery. If you really want to annoy your politically-correct seat-mate, mention that Ruth Beebe Hill was an active member of both the Daughters of the American Revolution and the Ayn Rand Institute.

THE CONFESSIONS OF NAT TURNER by William Styron: The author was a lifelong leftist and a close friend of James Baldwin. His book was a phenomenal success, winning a Pulitzer Prize for fiction and placing second on the list of the bestselling novels of 1967. So why should it enrage your politically-correct seat-mate? After its initial success, the book began drawing heavy criticism from African-American scholars and critics. Some didn’t like Styron’s portrait of Turner as a bumbling would-be revolutionary. Some didn’t like what they saw as a too-sympathetic portrait of wealthy southern plantation owners. Some didn’t like his treatment of inter-racial sexual attraction. These objections led to an anthology, William Styron’s Nat Turner: Ten Black Writers Respond, which was generally negative in tone. The book has survived the controversy. It has remained perpetually in print and is even included on some collegiate reading lists. Still, hyper-correct members of the illiberal Left, most of whom probably haven’t read the book, tend to turn up their noses at Styron’s act of ‘cultural appropriation.’

Anything by Elia Kazan: If The Confessions of Nat Turner finished in second place on the fiction bestseller list of 1967, what masterpiece of American literature finished in first place? Believe it or not, it was The Arrangement, a novel by film director Elia Kazan. Is it any good? In a word, no. But Kazan’s name on the cover of a book should be enough to annoy any right-thinking progressive, because Kazan appeared before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1952 and named names. Kazan wrote five novels, none of them distinguished, but a couple of them are at least fun to read in a so-bad-it’s-good kind of way. My personal favorite is The Assassins, in which Kazan’s hero, Master Sergeant Cesario Flores, murders a man in cold blood because the man is—wait for it—a hippie! James Baldwin provided a blurb for the paperback, and it’s a masterpiece of noncommittal-ness: “The tone of the book is extremely striking, for it really does not seem to depend on anything that we think of as a literary tradition, but on something older than that: the tale being told by a member of the tribe.”

THE SATANIC VERSES by Salman Rushdie: When The Satanic Verses was first published in 1989, most liberals considered it something like a duty to rush out and buy a copy. For writing the book, the author was rewarded with a death sentence by Ayatollah Khomeini. In those long-ago days, progressive thinkers objected to any kind of book-banning. Thus, the book became the sixth bestselling novel in America for the year 1989. But things have changed. Since September 11, 2001, the Left has become extremely deferential to all things Islamic. President Obama was criticized by right-wing commentators for refusing to even utter words such as “Islamo-fascism” or “Islamic terrorism.” Left-wing newspapers, meanwhile, go out of their way to avoid triggering an Islamic backlash by refusing to publish depictions of the Prophet Mohammad in their pages (this is understandable, considering the disastrous consequences the publishers of Charlie Hebdo suffered for violating this policy). Nowadays if you’re caught reading The Satanic Verses you’re more likely to be construed as an enemy of Islam rather than as a defender of free speech. But who cares what the politically correct think?

THE FAR PAVILIONS by M.M. Kaye: Rushdie wouldn’t like to see his book cheek-by-jowl with this one. In his essay “Outside the Whale,” he had this to say about the TV adaptation of Kaye’s novel: “Now of course The Far Pavilions is the purest bilge. The great processing machines of TV soap-opera have taken the somewhat more fibrous garbage of the M.M. Kaye book and pureed it into easy-swallowing, no-chewing-necessary drivel.” Rushdie considers Kaye’s writings about India to be part of a long line of “fake portraits inflicted by the West on the East.” But M.M. Kaye was born in India and spent the first ten years of her life there. She spoke Hindustani before she spoke English. She was sent to England for some formal schooling, but she later returned to India to get married and raise a family. Though she spent the last several decades of her life in England, her last will and testament instructed her heirs to scatter her ashes upon Lake Pichola in the Indian state of Rajasthan.

Like many of the daughters of British colonial officers, Kaye was a woman torn between two cultures and not fully accepted by either of them. If her India was more romantic and melodramatic than Rushdie’s, it was nonetheless born of a genuine love for the land of her birth. The romanticism of her novels was a deliberate attempt to offset the wholly negative view of the British Raj that was presented in most serious novels of the era. In her memoir The Sun in the Morning she wrote: “Too many people have already written, or are engaged in writing, ‘committed,’ politically slanted or fashionable books for me to try adding to their number. Yes, there was poverty, squalor and starvation; drought and famine; epidemics and corruption…But if I do not choose to write much about such things it is because I know I can safely leave that to the legions who can—and are only to eager to do so.” She held E.M. Forster’s A Passage To India in particular contempt, a book she considered “an anti-British fairy-tale.” In her memoir she asked rhetorically if any of these anti-Raj writers ever do any research on the Raj:

…or are they so anxious to blacken its name that they invent these tales deliberately, as E.M. Forster invented some of the preposterous statements he made in that virulent attack on his own race, A Passage to India, a book that seems to be regarded as Holy Writ by the trendy who have swallowed every word of it and for some reason like to think the very worst about the British in India. Forster has been equally slanderous and nasty about Indians. Nastier, in fact—though none of his admirers has chosen to notice that. Or perhaps they think the Indians are not quick enough on the uptake to know when they are being insulted.

With her great imagination, M.M. Kaye would likely have been a successful novelist no matter where she was born. To fault her for writing about India, is to fault her for having been born there. If you love a great big fat romantic adventure novel, ignore the cultural snobs and dive into The Far Pavilions, the fourth bestselling novel of 1978, according to Michael Korda. (Korda’s own novel, Queenie, about the rise of an impoverished girl from India to Hollywood stardom is itself an insanely entertaining act of cultural appropriation.)

GONE WITH THE WIND by Margaret Mitchell: You knew this was coming. The bestselling novel of both 1936 and 1937, Gone With The Wind remains one of the most popular American novels of all time. Had it been written by a man, it might be ranked alongside From Here To Eternity and The Red Badge of Courage as one of the greatest of all American war novels. Having been written by a woman, it has generally been categorized as a romance novel. And nowadays it’s likely to be categorized as a racist romance novel. It’s true that Mitchell wasn’t much interested in portraying the evils of slavery. Hers is a rather romantic version of the antebellum (and bellum) South. You shouldn’t read this book (or any other) uncritically. But you should read it. It’s beautifully written and fiendishly plotted. Nobody faults James Jones for the fact that his novels don’t fully explore the racism of the segregated U.S. Army during World War II. For the most part, he tells his stories through the eyes of working-class white men, who probably weren’t bothered much by racism. Likewise, Gone With the Wind is told through the eyes of Scarlett O’Hara, a daughter of the Southern aristocracy. It makes sense that she doesn’t care to dwell on slavery. Had Gone With the Wind been written by a man, the quest for the Great American Novel might have been settled in 1936. Instead, Mitchell’s work has been generally denigrated as The Great American Pop Fiction. Literary snobs might object to its melodrama and accessibility. Illiberal leftists might justifiably object to its white-washing of the horrors of slavery. But go ahead and read it anyway. Few American novels have ever been as absorbing as this one.

THE GOOD EARTH by Pearl S. Buck: In a review she posted at Goodreads.com, the author Celeste Ng wrote: “It’s difficult for me to explain how much I hate this book.” And then she goes on to mention, among other things, “the weirdness that arises from a Westerner writing about a colonized country.” Ms. Ng was born in Pittsburgh, PA, grew up in Shaker Heights, OH, and attended nothing but exclusive American schools, including Harvard University. Ms. Buck, on the other hand, was taken to China by her American missionary parents when she was five months old. She was raised largely by a Chinese nanny, spoke Chinese before she spoke English, and spent most of the first 40 years of her life in China. If a 40-year-old Vietnamese-born writer who came to America at five months and spoke English as her first language were to publish a novel about white Americans, would she be castigated for being an Easterner writing about the West? I can’t imagine it. Don’t listen to the haters. Buck was no cultural appropriator (whatever that might be). She knew China as well as anyone who has ever written about it. Buck was born into a country (the U.S.A.) where women had few rights, and she was raised in another country (China) where women had few rights. When she reached adulthood, she still wouldn’t have been allowed to vote in the U.S. and would have had trouble pursuing any kind of credentialed profession. Instead, she turned her considerable intellect and imagination to one of the few creative avenues open to gifted women of the era, the production of literary works. To punish her now for having written about pretty much the only subject matter she was an expert on, Chinese life, is to retroactively deny her even more rights. Read her books, and do so without apology.

* * *

Your assignment for this year’s Banned Books Week is to read a novel that, although it may not be banned in your local high school, probably isn’t promoted there either. Liberals claim to be the great champions of problematic literature. Test their tolerance by going out in public this month and reading a book that’s sure to annoy them.