Top

The UK Labour Party and the System of Diversity

The Tribe is an articulate, scrupulously fair but nonetheless root-and-branch attack on the ‘system and administration of diversity’, not only in UK Labour but also in other British institutions, including the civil service and the BBC.

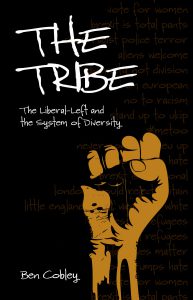

A review of The Tribe: The Liberal Left and the System of Diversity, by Ben Cobley, Imprint Academic, (July 9, 2018) 250 pages.

In February this year, I joined Artists for Brexit. AfB is an umbrella organisation for creatives who either voted Leave or who voted Remain but nonetheless want the best from Brexit for the arts.

Its membership ranks were nothing short of a revelation to me.

Until joining Artists for Brexit, I’d never met a left-wing Leaver. Of course, anyone looking at a map of the United Kingdom after the vote could see how vast swathes of Labour’s heartland had joined hands with the Shires to vote Leave. I genuinely did not know what mattered to leftie Leavers, something sadly indicative of the social divisions Brexit exposed. So I made a point of finding out, both within AfB’s membership as well as more widely. My suggestion — made somewhat glibly — to some that they ‘just vote Tory’ often generated a stream of unprintable invective. No-bloody-way-were-leftie-Leavers-just-voting-Tory-thank-you-very-much.

Of all the ‘leftie Leavers’ I met, none was more thoughtful than Ben Cobley, a committed Labour Party activist who’d been run out of his own party on a rail in large part for supporting Leave. He resigned a few days before the Referendum:

It has been a major feature of the EU referendum campaign — and as someone who came out in favour of Leave, the barrage of abuse but mostly insinuation and innuendo has been quite tough to bear, not least when much of it is coming from fellow Labour members and promoted by senior politicians (although not Jeremy Corbyn, notably). To vote for leaving the EU is to be ignorant, uneducated, racist, intolerant, anti-immigrant, anti-European, choosing the past over the future, supporting the far right and even supporting the murder of Jo Cox MP — so we are told. Seeing so many Labour people leading this chorus has tipped me over the edge, albeit I was already at the edge.

I knew Cobley was writing a book on what was ailing UK Labour. Having now read it, I maintain The Tribe: The Liberal Left and the System of Diversityto be among the most valuable books published this year.

I expected a lament on the extent to which Labour is no longer the party of the working class but rather a party of what Thomas Piketty calls ‘The Brahmin Left’, but it is much more than that. The Tribe is an articulate, scrupulously fair but nonetheless root-and-branch attack on the ‘system and administration of diversity’, not only in UK Labour but also in other British institutions, including the civil service and the BBC.

Before sketching out Cobley’s achievement in a form I hope does it justice, I should warn readers the book is rage-inducing. My review copy has two sets of dings in it because I threw it across the room twice. If you’re a Labour voter, you’ll be furious at how the party you support has been hollowed out from within. I found myself cross on Labour voters’ behalf and struggled to imagine how I would respond if something similar were to happen to the Conservative Party. If you’re a Conservative — and especially if you are part of British conservatism’s classical liberal wing, as I am — you will find Cobley’s barbs (often directed at classical liberal, pro-market economists when they join hands with left proponents of ‘the system of diversity’) are well aimed.

The Tribe describes how Britain’s Labour Party (and much of the wider labour movement, as well as other institutions) has been taken over (even ‘stolen’) by a political ideology that maintains we all have fixed identities, rather than being members of more malleable social classes. This ideology — Cobley calls it ‘the system of diversity’ — bears little relationship to the traditional Labour project. Instead of trying to raise up the poor and downtrodden by providing them with tools to organise and educate themselves, Labour — and institutions that feed it or recruit from its ranks — now exists to further a regime where we all exist in relationships of oppressor and oppressed with everyone else. These relationships of oppressor, oppression and power are always and everywhere based on fixed forms of identity: sex, race, religion (Islam, in particular, is rendered immutable), sexual orientation, gender.

Under the ‘system of diversity’, victimhood never ends. There is no room in it for the traditional trade unionist who wants better conditions for, say, coal miners so they don’t die underground; or a shop steward who wants call-centre workers or fruit pickers to earn better wages. There isn’t even room for the democratic socialist who aspires to any of the various forms of worker democracy that have existed historically, or who wishes to make use of alternative business structures, like cooperatives and mutuals. Instead, certain groups are taken always to require support. Certain groups must always be on the outer. Cobley calls them ‘the favoured’ and ‘the unfavoured’. The favoured include women, Muslims, and immigrants. The unfavoured include men and whites — but also uneducated people and most of the working poor. There are always victims, and always perpetrators. Oppression is systemic; it never ends, and can never end.

This has practical policy consequences. Cobley documents in mind-bending detail a regime of outrageous and systematic discrimination — in hiring, training, and in terms of financial largesse — across multiple institutions (including the BBC and civil service) and within Labour. The favouritism is meant to produce equality of outcomes, and diversity is treated as a per segood. ‘More women in STEM’ or ‘more BAME at the BBC’ or ‘more women in parliament’ are common catch-cries, with few arguments as to how this will improve STEM, the BBC, or Westminster. Even where there is an evidence base for ‘the system of diversity’ — Steven Pinker’s research showing an increase in the number of female parliamentarians produces more circumspect foreign policy — it isn’t used. Equality of outcomes is the only policy goal.

The scale of the favouritism and the precision with which it is targeted demands lock-step conformity, too, so when different favoured groups find themselves contesting the same territory, demarcation disputes arise. If, say, on the BBC, a feminist criticises the treatment of women in Britain’s Muslim communities or a Muslim outlines his religion’s traditional view of homosexuality, there is an embarrassing contretemps and ruffled feathers. Effectively, the two representatives can only be allies in ‘the system’ as long as the Muslim doesn’t say anything about homosexuality and the feminist doesn’t say anything about burkas or niqabs (which means the latter job is left to Tories like Boris Johnson). Rinse and repeat when it comes to other favoured groups.

So far, so simple — The Tribe may seem like many conservative (and Conservative Party) criticisms of ‘identity politics’ or ‘SJWs’ or the ‘ctrl-left’. But it isn’t. Cobley’s own fealty to the traditions of Labour and labour activism means he is a sympathetic and humane guide to ‘the system of diversity’. The Tribe is a real attempt to understand it on its own terms. Instead of having a witty 1,000 word moan (what Tories tend to do when confronted by ideas widely considered nonsense on the centre-right) Cobley elucidates the extent to which what has taken hold of Labour (and labour) is a worked-out ideological system with serious intellectual underpinnings. Often, of course, it’s deployed in grossly simplified form. In doing so, he is probably the first person I’ve read to discuss Heidegger with clarity and élan. From being a philosopher I always wrote off as a purveyor of fascist nonsense, Heidegger has now become an important but dangerous thinker.

Heidegger developed a digestible way of thinking about fixed identities when it comes to fitting out and then fighting an ideological battle. As described by Cobley, this involves construing group identity so it bleeds out all individual characteristics. People are treated only as an instance of their fixed group membership. It allows rapid categorisation and assessment (‘friend or foe?’ and ‘with us or against us?’) and also ensures activists who administer it and promote it don’t have to think about what they’re doing or the club they’ve joined. They become the vanguard of a ‘thought tribe’ instead of the proletariat.

This means one can predict a left-liberal activist’s opinion across dozens of subjects based solely on his or her participation in ‘the system’. Cobley documents — with mountains of evidence — the extent to which ‘system people’ cannot be engaged in debate, as well as the extent to which they are willing to hand over their ability to think in favour of what are evidentially unsupported assertions. They haven’t come to their views through self-discovery or introspection, they don’t really understand them, and any arguments where they do engage are combative and aimed at belittling interlocutors rather than making a persuasive case. This explains the endless demands to check one’s privilege or arguments for the primacy of lived experience over research or imagination or data, for example. A single piece of information about an opponent is used to rule out anything he or she says tout court. Cobley makes use of Heidegger’s phrase ‘Das Man’ to label this phenomenon, to which one ‘gives way’ or into which one ‘falls’. A useful translation of ‘Das Man’ in this context is ‘the Blob’. By ‘giving way’ to the Blob, people are relieved of the requirement to think. All they have to do is engage in duckspeak, thereby showing in-group loyalty.

Sexcrime

This can have disastrous effects. In the first 30 pages, Cobley tells the story of Rotherham through the lens of the system of diversity. He documents how leaders drawn from one of the system’s favoured groups — Pakistani Muslims — were able to cover up an extraordinary crime spree (at least 1400 children sexually abused in a single town). State institutions simply outsourced authority over that group to state-funded ‘community leaders’, especially Pakistani-background Labour Party councillors.

These individuals — by constantly referring to ‘community cohesion’ and making accusations of racism — were able to ensure police officers, teachers, and social workers from every kind of background were simply ignored when they pointed out that there was, in fact, a vast pool of criminality pullulating under their noses. Criticism was construed as an attack on a group the ‘system of diversity’ favours, or even on the idea of diversity or variation itself. Meanwhile, politicians and civil servants higher up the food chain (overwhelmingly posh, even though drawn from Labour) simply rescinded responsibility for their constituents. One social worker told the Rotherham Inquiry, ‘if we mentioned Asian taxi drivers we were told we were racist and the young people were seen as prostitutes,’ while another said ‘we were constantly being reminded not to be racist’.

This relationship is multiculturalist (relations conducted with certain favoured groups as groups [emphasis Cobley’s]; transactional (in that administration effectively trades power for assistance with the community); it outsources authority (from public bodies to community leaders); and it is hands off/not ethics-based (so disregards illegal behaviour in order to maintain the integrity of system relations) [p 9].

Cobley’s extended analysis of what went on in Rotherham, sharpened by his detailed knowledge of the internal workings of the Labour Party and the individuals involved, led to the first ding in my review copy.

One Labour MP (Rotherham’s Sarah Champion) did do the job of representing her constituents. And the full force of the ‘system’ was brought to bear in a way enormously destructive not only of her political career (which one expects, politics being a nasty game) but also of her ability to function as an adult human being. To outsiders (including Conservatives) it looked like she was in trouble for writing a piece about Pakistani Muslim grooming gangs for The Sun. Not so. She could have written the same piece for The Guardian and the response would have been identical. The system set out to break her. Among other things, she now requires 24-hour security and is routinely deluged with vile abuse. When Cobley then described how Labour’s posh feminists refused to move the levers of power on behalf of poor white girls who formed a genuine (as opposed to political) victim class — despite being made well aware, thanks to Champion’s efforts, of what was going on — I threw the book across the room.

Hatecrime

Rotherham is not, however, Cobley’s most compelling case study of the ‘system’ at work. That appellation belongs to his analysis of the surge in ‘hate crime’ following the 2016 Referendum result. I am now reasonably satisfied the hate crime widely reported from June 23 onwards and seized upon by the Remain camp after its shock defeat was a classic example of moral panic, and that most of the reports were false.

This is because no evidence is required for the reporting of hate crime, only the victim’s subjective feelings. Worse, many reports are not made to police, but to an online portal called ‘True Vision’, which allows (and encourages) anonymous submissions and also allows the alleged victim to forbid police follow-up. Even when contacted in person, police officers are not allowed to contest an alleged victim’s interpretation of events. They can’t even ask ‘are you sure?’ All of this is set out in grisly and authoritarian detail in the College of Policing’s Hate Crime Operational Guidance.

Thanks to the collapse of multiple trials, we now have good evidence that lowering the evidentiary bar in this way generates a rapid uptick in false reports. Lawyers have also long known any legal system that makes use of untested evidence from anonymous witnesses is vulnerable to perversions of the course of justice. Meanwhile, allowing alleged victims to define what is and is not racism on a wholly subjective basis undermines the ‘reasonable person test’ that undergirds much of the rule of law. The same phenomenon became apparent during the period when ‘believe the victim’ in sexual assault reporting was also part of police operational guidance. This has since been rescinded precisely because it undermines the presumption of innocence. Not so with hate crime, which remains on foot and able to be used as a stick with which to beat those opposed to ‘the system of diversity’.

In this way, hate crime and its reporting process have appeared as a handy political weapon to affix a legalistic form of guilt [emphasis Cobley’s] on to people who do not align to the system of diversity and its favouritisms, like on immigration. It has enabled high profile politicians like Sadiq Khan to use their power to influence the reporting of incidents, thereby affecting the statistical results which they then use for political ends — a variant of what The Wire creator David Simon has called ‘juking the stats’. It has helped activists and community leaders to promote their victimhood, claim that it is getting worse, and demand more resources to address it, reducing budgets for other things [p 17].

At one point, Labour’s abandonment of the rule of law was so complete that Andy Burnham — at the time Shadow Home Secretary — argued British Muslims should be able to bypass police when reporting hate crime. He wanted them to be able to go to a local mosque and its ‘community leaders’ to make reports instead.

There’s a name for the activity undertaken by this particular ‘favoured group’, although Cobley does not use it: ‘rent-seeking’. Rent-seeking happens when people try to obtain economic benefits by dint of politics rather than market competition. They may seek subsidies for a good they produce or for being a member of a particular group of people, or by persuading legislatures to enact regulations hampering competitors.

Key to understanding rent-seeking’s pernicious effect on the economy and wider society is that it involves increasing a given group’s share of existing wealth without creating any new wealth. It is typically legal but often produces disreputable behaviour, and can shade into bribery and vote-rigging, which are illegal. Cobley documents a number of incidents where rent-seeking crossed into actual criminality. He outlines how Faiz ul Rasool, chairman of the Muslim Friends of Labour, was in the habit of boasting of his ability to provide access to Andy Burnham for £5000, for example. ‘There are four people fighting this election,’ ul Rasool would say. ‘Whoever wins, they will come to me because I’ve got 1.5 million votes. I have got a position’ [p 171].

Cobley is a genuine lefty, and to be frank I doubt he’s ever read an economics textbook. In The Tribe he seems to have worked up concepts drawn from public choice theory independently of any research in the field. Clearly both moved and horrified at his discoveries, he documents them with meticulous clarity, to the point where his chapters on Rotherham, hate crime, and the use of ‘community leaders’ to manage and police Pakistani Muslims (instead of the state) could be set in a microeconomics course alongside theoretical papers from the likes of Anne Krueger, Gordon Tulloch, and James Buchanan — core theorists of public choice.

Doublethink

After his superb discussion of rent-seeking, Cobley moves on to immigration policy. He seeks to pick apart the current cooperation between centre-right economic liberalism (‘immigration is good for the economy’; ‘immigrants have more market value than natives’) and the system of diversity (‘immigrants are structurally disadvantaged’; ‘immigrants are oppressed victims’). He makes classical liberals look like smarmy gits, worthy of the nasty ‘neoliberal’ moniker.

‘Preferment towards immigrant populations [is] justified both for their situation as victims and based on a survival of the fittest story,’ he points out, ‘often by the same people’ [p 126, emphasis Cobley’s]. The doublethink involved is obvious. The leftie diversity-booster wants to tell a story about the poor Syrian refugee fleeing from Assad’s gas attacks, while the Tory or LibDem neoliberal wants cheap labour to mow his lawn or clean her floors (because natives demand higher wages). Both, however, sing from the same hymn-sheet in an utterly cynical alliance of convenience.

During a nuanced discussion of how people who do not like immigration do not necessarily think immigrants are bad (an important point undergirding data analysis showing employment discrimination against women and minorities in modern Britain is rare), Cobley’s lack of economic knowledge is nonetheless quite badly exposed. I’m reluctant to say this. Often ‘but you should have addressed [x]’ is a complaint the writer hasn’t written the critic’s preferred book. Nonetheless, The Tribe is so good Cobley’s failure to get labour economics correct is notable.

Drawing on Marx (with a side-serving from Karl Polanyi’s Great Transformation), Cobley takes it as given that immigrants compete for jobs and put downwards pressure on wages. He even quotes Marx’s observation (made in 1870) that surplus labour from Ireland lowered ‘the material and moral position of the English working class’ and is ‘the secret by which the capitalist class maintains its power’.

There’s a problem with this argument. It isn’t true. And drawing on two thinkers whose empirical analysis is suspect led to the second ding in my review copy.

The effect of immigration on wages is now fairly well known. Research by labour economists indicates it doesn’t have a negative effect on native wages, in large part because immigration makes the economy bigger (it’s ‘positive sum’, not ‘zero sum’). Where economists do suggest immigration is a problem — Harvard’s George Borjas is notable here — it’s only low-skill immigration at issue. Borjas’s most famous study looks at the Mariel Boatlift in Miami. He found that wages for native born school drop-outs (a significant share of the labour market in Florida) fell by up to 15% relative to other cities over the next 5-10 years before recovering in the late 1980s. If Borjas is right, then low-skilled immigration can depress the return on pure, or manual labour for up to 10 years — especially if the labour market is already rigid or education and retraining systems are (forgive the Keynesian language) ‘sticky’.

However, when one sees a long-term negative effect from immigration — as opposed to just a transitional one — that means there are labour market rigidities like wage controls or limits on hiring and firing or poor geographical mobility. The effect of low-skill immigration in France, for example, is consistently negative and has been for a long time. France combines an inflexible labour market with a generous welfare state for citizens, while low-skill immigrants are more willing to work at the same wage under less pleasant conditions. Meanwhile, Denmark tells a very different story — low-skill immigration there has a strongly positive effect. Denmark has a flexible labour market and no minimum wage, which it combines not just with a social safety net but also systems to retrain the native workforce for non-manual tasks as migrants replace them at the bottom of the job heap.

This means progressives are confronted with a situation where they have to choose. Do they opt for extensive worker protections? Or do they shield the poor from negative migration effects? And do they admit (while making their choice) that squaring this circle is both expensive and occasionally morally repugnant? Denmark is willing to spend big on its social safety net and behave coercively towards immigrants who don’t integrate readily. Australia, meanwhile, makes it almost impossible for asylum seekers and low-skill immigrants to enter the country (helping to keep minimum wages high and unemployment low), all the while aggressively enticing and recruiting large numbers of high-skill immigrants from all over the planet.

Ingsoc

During a conversation with Cobley last month, he told me sundry Westminster wonks were irritating him because they would read his book and then complain he fails to provide solutions to the problems he so superbly analyses. I told him that, in my view, it’s a policy wonk’s job to come up with useful policy hacks. He’s already done his bit.

Cobley builds up a detailed portrait of systemic discrimination against an already disadvantaged group (poor whites, particularly poor white men). He may well have proven that social policy around ameliorating disadvantage has been misdirected, even flat wrong, for something like 20 years. Along every metric that matters — education, wealth, life expectancy, suicide rates — poor white men and boys are at the bottom of the heap, yet are weirdly written off as ‘privileged’ by the system of diversity.

My policy advice here is of a fairly standard classical liberal sort, a version of the City’s ‘Big Bang’ (which had the beneficial effect of breaking up cosy old-boy networks). Parliament should enact legislation that systematically and swiftly ends all state funding for ‘diversity lobbies’ or ‘community organisations’, whether ethnic minority, feminist or religious. At the same time, it should abolish all forms of hiring preferment and quotas in the civil service and BBC, while discouraging similar forms of discrimination in the private sector. Law enforcement and social services should engage people directly, as individuals, not via ‘community leaders’.

This, however, only addresses part of the problem, because it would also make Britain’s institutions brutally meritocratic. Never forget that meritocracy is the way smart people want society organised so members of their tribe — other smart people — can escape whatever world they’ve been born into. Meritocracy may or may not be a good way of managing civilisation, but don’t kid yourself it’s any fairer to reward people born smart than it is to reward men with posh surnames, Pakistani Muslims, women, or immigrants. I have no good responses to this conundrum.

The problem with the system of diversity is that its focus on equality of outcomes across groups undermines what classical liberals call ‘moral egalitarianism’. Moral egalitarianism means we must weigh everyone’s interests equally, regardless of anything else about them. Our attributes and talents don’t determine how valuable we are as human beings. Our humanity comes first, because humans are equal in dignity and worth.

The uncomfortable reality is a meritocratic society is an unequal society, because those who are more talented in particular areas do better. These days, for example, STEM is valued, and STEM (in the face of major programmes to entice or even shoehorn more women into those fields) is male-dominated. If despite the strenuous efforts Cobley documents STEM remains male-dominated, it gets easier to suggest — ‘well, maybe women aren’t equal, so maybe we can take their interests less seriously’.

One of Steven Pinker’s concerns has been to show that the principle of moral egalitarianism can survive the reality people are not all the same. That some people — both individually and on a group basis — are better at sums or faster in the fifty-yard dash seems trivially true. Unfortunately, much current policy is dedicated to handwaving away large average statistical differences across groups. Worse, people are born unequal, too — our aptitudes and interests have a genetic basis. To turn the famous line from Julius Caesar on its head, the fault is in our stars and not in ourselves that we are underlings. This is something we haven’t confronted honestly since classical antiquity, which probably explains how such thoughtless policy become popular. It’s worth remembering it took centuries to reject the pagan Roman view that if you’re beautiful, or clever, or courageous, you’re a better person and deserve more consideration.

All the while equality of outcomes is sought but not achieved, the foundation of liberal democracy is at risk: equal suffrage or ‘one-vote-one-value’ and equal treatment before the law. We are in danger of making moral egalitarianism dependent on equality of outcomes.

In writing The Tribe, Ben Cobley has done the tradition of English socialism an enormous service. He has also produced a book that explains many of the perplexities arising from the UK’s Leave vote, detailed how a frankly bonkers set of beliefs has stolen the Labour Party, and shown the danger of viewing people as members of fixed identity groups. I’m not a socialist and am temperamentally disinclined ever to be one, but The Tribe is a better analysis of the fraught nature of identity politics and mandated diversity than anything from my side of the political aisle. People of all political persuasions should read it.