Arts and Culture

Journalism in the Age of the Populist Right

Bannon’s deplatforming has reignited the debate about the responsibilities that mainstream event organisers and media broadcasters have when giving a platform to far-right views, and what limits we should place on public discourse.

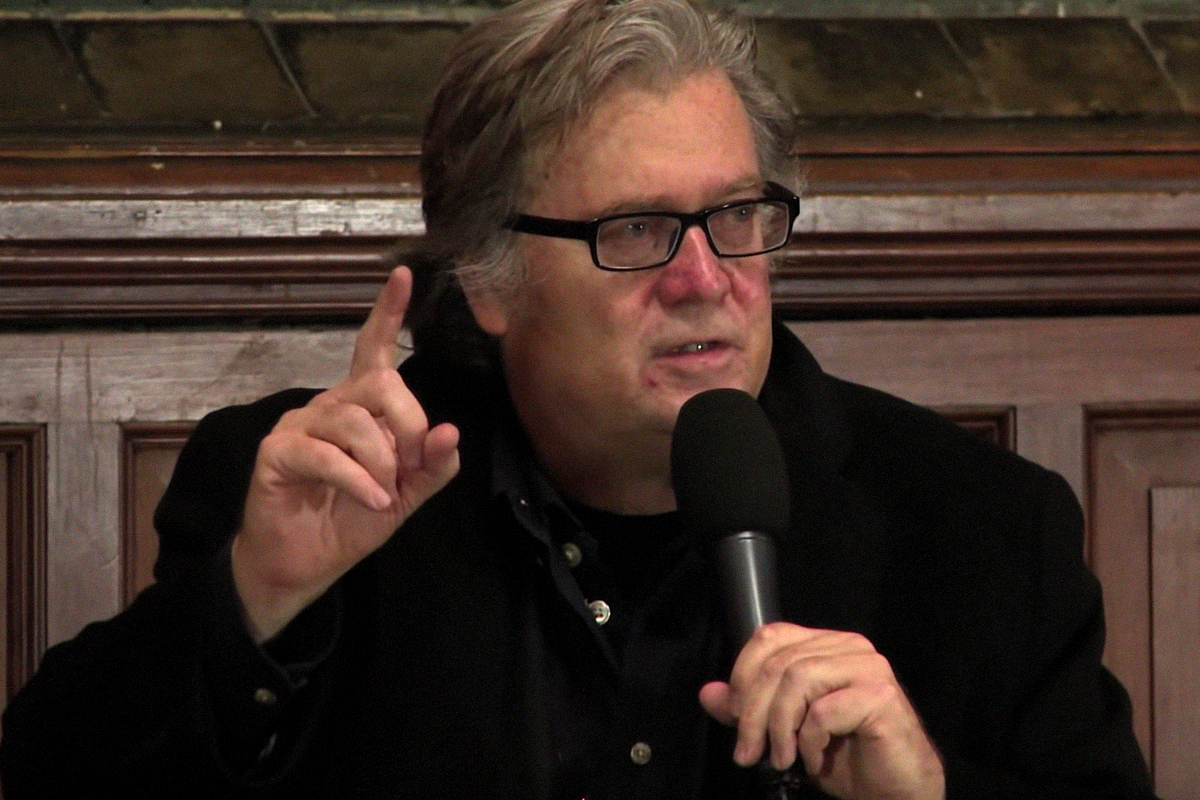

Yesterday, Steve Bannon was dropped from a headliner at the New Yorker’s yearly ideas festival after a backlash from readers, potential audience members and other speakers who were also slated to attend.

Bannon? And me? On the same program?

Could never happen.

— Jim Carrey (@JimCarrey) September 3, 2018

Bannon was headlining the festival, with Jim Carrey, Haruki Murakami, Zadie Smith and Jimmy Fallon also on the bill. In explaining Bannon’s inclusion on the line-up, the New Yorker’s editor David Remnick told the New York Times that: “I have every intention of asking him difficult questions and engaging in a serious and even combative conversation.”

But the opportunity for a combative conversation did not come to pass. After a backlash online, with several celebrities declaring that they would no longer attend the festival, Remnick reversed his decision. In his announcement he wrote “I don’t want well-meaning readers and staff member to think that I’ve ignored their concerns”.

A statement from David Remnick, editor of The New Yorker, explaining his decision to no longer include Steve Bannon in the 2018 New Yorker Festival. pic.twitter.com/opayiw5GQ2

— The New Yorker (@NewYorker) September 3, 2018

Bannon is still slated to appear at The Economist’s yearly festival and was recently interviewed by Australia’s national broadcaster, which aired on Monday night.

In the past, Bannon has expressed opposition to immigration to the United States, contradicting a long-held consensus amongst the American political class. He views secularism and Islam as twin existential threats against declining Judeo-Christian values, believing the West to be in a civilizational struggle against these forces. Many on the right and left are likely to fundamentally disagree with his project of agitating for a populist revolution based on economic nationalism. However, regardless of what we might think of this type of worldview, he has also expressed views that might have broader appeal and offer insight into the present moment.

In a 2014 speech to a conference at Vatican, Bannon spoke about the fallout from the 2008 global financial crisis, arguing that the wealth created in the intervening period had gone to corporate elites in the upper classes at the expense of workers. He also railed against the corporate bailouts, and what he sees as an unholy alliance between big government and big business:

The bailouts were absolutely outrageous, and here’s why: It bailed out a group of shareholders and executives who were specifically accountable… these major corporations that are in bed with the federal government are not what we’d consider free-enterprise capitalists… They’re what we call corporatist.

What struck me about this characterization of the events since the GFC was not that they were obviously right wing, but that they could just as easily have been uttered by Naomi Klein or Noam Chomsky, or even Bernie Sanders. Surely such an alignment between the political poles on this particular issue might be worthy of discussion at the New Yorker Festival, insofar as it might have provided insight into where we might collectively diverge in our current political debate.

Bannon’s deplatforming has reignited the debate about the responsibilities that mainstream event organisers and media broadcasters have when giving a platform to far-right views, and what limits we should place on public discourse.

There seems to be two lines of thinking that play out in this debate, and more broadly about the theoretical models of how society should respond to those who hold extremist views.

The first narrative, adopted overwhelmingly by those on the left, is that merely putting Bannon on stage is both a step toward, and a product of, the normalisation of white supremacy and neo-Nazi ideas. Under this assumption, Bannon could only come out ahead – irrespective of how well or badly he performs in any interview. It’s thought that any platform is a good platform, as it gives these types of figures mainstream exposure of their otherwise unsavoury ideas.

We might call this a ‘normalisation’ model of societal response, where a normal distribution of political views in the population is thought to shift rightward simply by virtue of them being legitimised by speaking engagements. Right wing ideas are thought to exert a kind of gravitational force on us, pulling the Overton Window closer toward racism and prejudice simply by being expressed. Therefore, the normalisation model demands that unsavoury views are never entertained by mainstream media platforms, because they are a mechanism through which society will come to embrace those ideas.

Another, competing narrative is based on what we might call an ‘immunisation’ model of societal response, which sees mild exposure to a threatening phenomenon as having the potential to help build resistance to it. It allows us to refine our arguments against those we disagree with – in Bannon’s case the populist right – and to remind us of where we stand as a liberal democratic society.

Those subscribing to the normalisation model tend to be concerned with questionable ideas being expressed when those ideas are associated with the political right. But if the model is to hold in a politically unbiased way, they should be equally concerned about the mainstream platforming of extreme ideas from other political origins as well. This doesn’t tend to be the case.

What’s lost in the discussion is the acknowledgement that it is the role of the media and the journalist, in particular, to dig deeper into the ideas, attitudes and motivations of influential people. It’s the duty of the journalist to highlight incriminating evidence against people who would prefer that it remain obscured. It’s the duty of the journalist to ensure the viewer has clarity about a person’s views, lest they hide behind ambiguity. It’s the duty of the journalist to draw attention to the distinctions between what they say to their followers, and what they are saying during an interview.

An example of these duties being fulfilled can be seen in Christopher Hitchens’ 1991 CNBC interview with John Metzger, a leading member a white separatist movement that celebrates the birth of Hitler, believes in a Zionist occupied Government (ZOG), and believes in the inherent superiority of white-skinned European descendants. In the course of the discussion Metzger fails the most elementary of tests that we might use to take him seriously, by repeatedly failing to acknowledge the historicity of the Holocaust. Hitchens also calls him on the discrepancy between the pro-Hitler material found in his organizations newsletters and the way he attempts to present a more ‘watered down’ version of his politics in the interview.

It’s difficult to see how this interview would have normalised neo-Nazi ideas, but that outcome is almost entirely due to Hitchens performance as a journalist. Metzger was forced to defend his views on Hitchens’ terms, and ours. As a result his conspiratorial, race-obsessed, historically denialist views were laid bare for all to see, without being smoothed over for public relations purposes. In my view, this platforming episode serves as an example of immunisation against far-right ideas, rather than a normalisation of them. Anyone tempted to stroll down the trail toward the far right were shown precisely where it led.

A counterpoint could be made that we can still discuss controversial political views without having to interview people who actually hold them at festivals or on broadcast television. This seems unlikely, since those figures can always claim they are being misrepresented if they’re never given the opportunity to speak for themselves, further entrenching their victimhood status amongst their followers. It’s more difficult to claim that you’re being misrepresented when you’re the one answering the questions.

In our current age of social media there’s no shortage of people producing content with views that, if widely adopted, would undermine our liberal democratic society. We can’t stop people from producing this content, and if we’re at all interested in free speech, we shouldn’t be interested in doing so either. However, most of the time they produce this content on their own terms, outside the mainstream media space. By occasionally providing a window into the mind of those who wish to orchestrate a populist revolution through critical but honest discussion and debate, mainstream news organisations can serve the public good without normalising otherwise extreme views.

This isn’t to say broadcast television or event organizers should make a regular habit of interviewing extremists from any aspect of the political spectrum. Insofar as these types of appearances might incentivise the pursuit of controversy, views, and revenue, we should be wary of any organisation that seeks to monetise the outrage economy. But the importance of hearing ideas from the horse’s mouth, and providing vigorous pushback where necessary, should not be understated. Done properly, it can equip people with the conceptual tools to build immunity to political radicalisation.