censorship

How Much Real-World Extremism Does Online Hate Actually Cause?

While calls to censor hate speech and violent extremist content on social media platforms are common, there’s little evidence that online incitement leads to real-world radicalization. Ironically, such calls may actually galvanize extremists, who interpret hostile media coverage, commentary, and censorship policies as confirmation of their victimhood narratives and conspiratorial thinking.

A 2018 journal article entitled “Exposure to Extremist Online Content Could Lead to Violent Radicalization: A Systematic Review of Empirical Evidence” scanned the content of more than 5,000 previous studies, but found that only 11 included “tentative evidence that exposure to radical violent online material is associated with extremist online and offline attitudes, as well as the risk of committing political violence among white supremacist, neo-Nazi, and radical Islamist groups.” The authors acknowledged that they could not conduct a systematic meta-analysis “due to the heterogeneous and at times incomparable nature of the data.” To the extent generalizations were possible, the authors reported that “active seekers of violent radical material [appear] to be at higher risk of engaging in political violence as compared to passive seekers.” If that is the case, then preventing extremist content from being published on large-scale social-media platforms is unlikely to be highly effective, as it is primarily being consumed by those who already have committed to its message.

In 2013, the RAND corporation released a study that explored how Internet usage affected the radicalization process of 15 convicted violent extremists and terrorists. The researchers examined five hypotheses generated by a review of the existing literature:

- The Internet creates more opportunities to become radicalized;

- The Internet acts as an “echo chamber,” in which individuals find their ideas supported and echoed by like-minded individuals;

- The Internet accelerates a pre-existing process of radicalization;

- The Internet allows radicalization to occur without physical contact; and

- The Internet increases opportunities for self-radicalization.

The researchers found that the Internet generally played a small role in the radicalization process of the individuals studied, though they did find support for the idea that the Internet may act as an echo chamber and enhance opportunities to become radicalized. However, the evidence did “not necessarily support the suggestion that the internet accelerates radicalization, nor that the internet allows radicalization to occur without physical contact, nor that the internet increases opportunities for self-radicalization, as in all the cases reviewed … the subjects had contact with other individuals, whether virtually or physically.”

The limited empirical evidence that exists on the role that online speech plays in the radicalization-to-violence journey suggests that people are primarily radicalized through experienced disaffection, face-to-face encounters, and offline relationships. Extremist propaganda alone does not turn individuals to violence, as other variables are at play.

Another analysis compiled every known jihadist attack (both successful and thwarted) from 2014 to 2021 in eight Western countries. “Our findings show that the primary threat still comes from those who have been radicalized offline,” the authors concluded. “[They] are greater in number, better at evading detection by security officials, more likely to complete a terrorist attack successfully and more deadly when they do so.”

Even less scientific rigor has been applied to the presumption that removing hate speech and misinformation from social media platforms will have a net positive result. While we will not see the true impact of recent social-media content restrictions imposed by such sites as Facebook, Google, and Twitter, a 2019 study from George Washington University detailed a model that predicted “policing within a single platform (such as Facebook) can make matters worse, and will eventually generate global ‘dark pools’ in which online hate will flourish.”

“The key to understanding the resilience of online hate lies in its global network-of-network dynamics,” the authors wrote. “Interconnected hate clusters form global ‘hate highways’ that—assisted by collective online adaptations—cross social media platforms, sometimes using ‘back doors’ even after being banned, as well as jumping between countries, continents and languages.” Banning specific words and memes can cause them to mutate and spread, to the delight of online trolls.

A more recent analysis by the same team scrutinized hate speech and COVID-19 misinformation associated with the white-supremacist movement and “medical disinformants.” They reviewed six platforms that included both mainstream and alternative social media networks: Facebook, Instagram, Gab, 4chan, Telegram, and VKontakte. Researchers found that harmful content, including hateful posts and COVID-19 misinformation narratives, spread quickly between platforms; with hyperlinks acting as “wormholes” that transport users:

An extremist group has incentives to maintain a presence on a mainstream platform (e.g., Facebook page) where it shares incendiary news stories and provocative memes to draw in new followers. Then once they have built interest and gained the trust of those new followers, the most active members and page administrators direct the vetted potential recruits towards their accounts in less-moderated platforms such as Telegram and Gab, where they can connect among themselves and more openly discuss hateful and extreme ideologies.

This funnelling behavior (as one might call it) is an expected result of network-migration techniques adapting to censorship policies: Recruiters’ communication with highly motivated individuals is selectively moved from content-restricted channels such as Facebook, to channels that permit a much greater range of content. But how many violent extremists (or borderline violent extremists) have been recruited, even indirectly, through Big Tech platforms? And how many radicalized individuals have been deradicalized through these same channels?

On a few occasions, the Minds social network has been accused of giving a forum to extremist content. But the inconvenient truth is that solving the problem of hateful extremism (as opposed to hiding it), requires a process of long-term communication that involves these affected individuals.

Big Tech censorship policies can be expected to cause a migration of information from large-scale platforms (where feedback from a general population may serve to counter and moderate extreme views) to smaller platforms, where extreme beliefs can be reinforced by others who have also been banned by larger platforms. This creates powerful echo chambers in which controversial ideas are reinforced and then carefully reworded for reintroduction into mainstream social-media spaces.

Moreover, enhanced efforts to police large-scale platforms promote further narratives of censorship and victimhood, and can thereby increase the commitment level of those who have already invested in the extremist message. As Erin Saltman, formerly Facebook’s Head of Counterterrorism and Dangerous Organizations Policy for Europe, the Middle East, and Africa, has written:

Online terrorism and violent extremism are cross-platform and transnational by nature. Nobody has just one app on their phone or their laptop, and bad actors are no different. [Thus] any efforts trying to effectively [oppose] terrorism and violent extremism need to similarly go beyond one-country, one-platform frameworks.

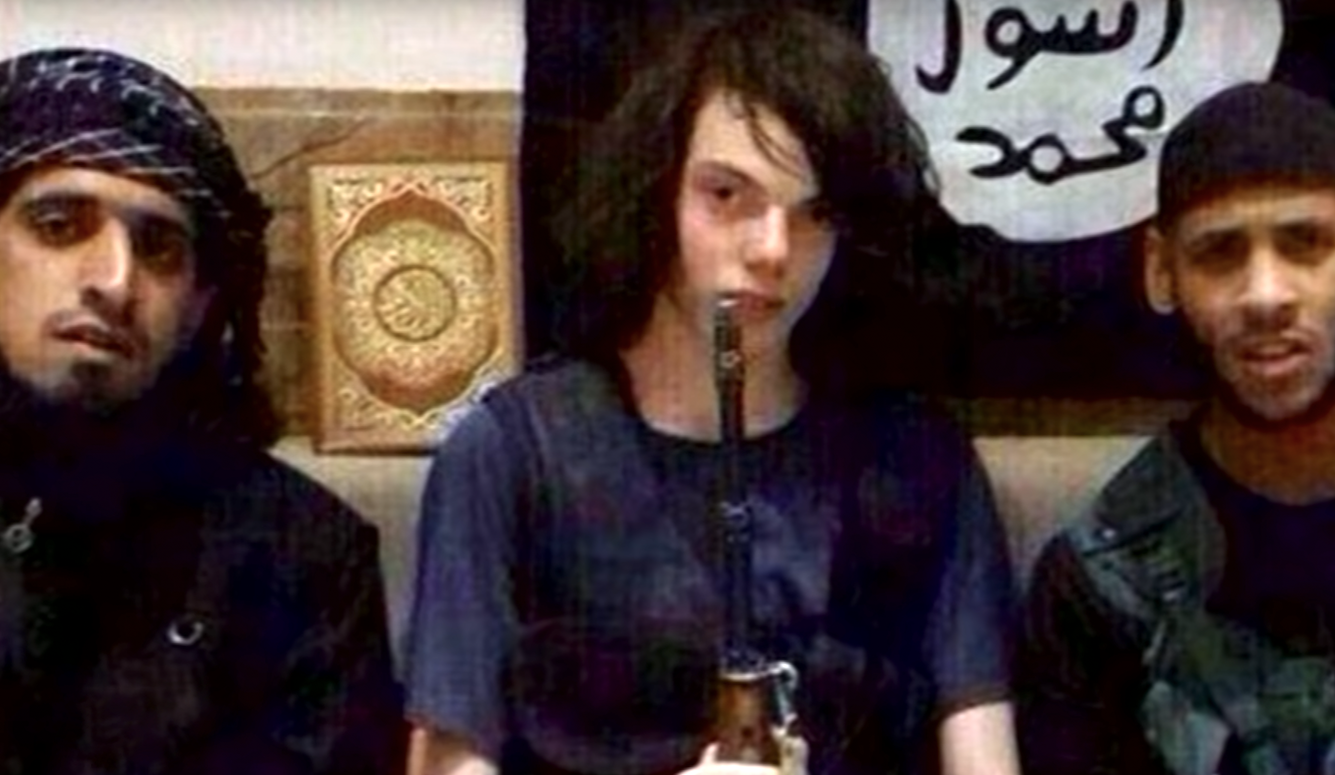

Mainstream social-media companies’ focus on content removal can be traced in large part back to the rise of ISIS and its caliphate in 2014. A seminal Brookings study, “The ISIS Twitter census: Defining and describing the population of ISIS supporters on Twitter,” found between 46,000 and 70,000 active pro-ISIS Twitter accounts. Soon thereafter, Twitter suspended a large number of them. Yet the effect of this blunt approach is unknown, and could produce ominous ramifications. And the report’s authors themselves stressed that

while suspensions appear to have created obstacles to supporters joining ISIS’ social network, they also isolate ISIS supporters online. This could increase the speed and intensity of radicalization for those who manage to enter the network, and hinder organic social pressures that could lead to deradicalization … Further study is required to evaluate the unintended consequences of suspension campaigns and their attendant trade-offs. Fundamentally, tampering with social networks is a form of social engineering…

The same authors released a subsequent paper in 2016 that detailed the potentially negative impact of deplatforming. Titled “The Islamic State’s Diminishing Returns on Twitter: How Suspensions are Limiting the Social Networks of English-speaking ISIS supporters,” it analyzed a network of English-language ISIS supporters active on Twitter from June to October 2015, and concluded that “suspensions held the size and reach of the overall network flat, while devastating the reach of specific users who have been repeatedly targeted.”

But the report also described the effects of extremist adaptation, noting that Telegram Messenger had emerged as a favored alternative to Twitter for the initial publication and dissemination of Islamic State propaganda. Telegram, a private messaging platform, is almost impossible for law enforcement agents to systematically monitor. And in November 2015, as Twitter increased its account-suspension efforts, an ISIS-affiliated cell used Telegram to communicate as they killed 130 people in a series of coordinated attacks across Paris in what became the deadliest jihadist attack in French history.

The report noted that similar content-moderation recommendations may have analogous effects in regard to far-right extremism. Millions of conservatives migrated to Telegram after Twitter and Facebook shut down then-president Trump’s accounts, for instance. This was followed by Amazon, Apple, and Google removing Parler, a social media site that grew by millions in the wake of the US election, largely because it touted itself as a place to “speak freely and express yourself openly without fear of being deplatformed for your views.”

Adapted with permission from The Censorship Effect: An analysis of the consequences of social media censorship and a proposal for an alternative moderation model, authored by Bill Ottman, Daryl Davis, Jack Ottman, Jesse Morton, Justin E. Lane, and F. LeRon Shults.