identity politics

Identity Politics Does More Harm Than Good to Minorities

The day is fast approaching when mainstream white society will react to accusations of racism with yawns and shrugs. What will identitarians do then?

It is difficult to think of an issue today as contentious as identity politics. Long criticised by the right as divisive and polarising, it has begun to be questioned by some on the left as well – from thinkers such as Mark Lilla and Jonathan Haidt. Writing from a liberal perspective in the Guardian, Columbia University professor Sheri Berman cited a host of psychological surveys showing that many white voters are supporting right-wing populists like Trump in a “defensive reaction” against perceived “group-based threats” that have been provoked, in part, by left-wing identity politics.

Berman’s article – “Why identity politics benefits the right more than the left” – insisted that liberalism’s goal must be “winning elections,” which means “not helping Trump rile up his base by activating their sense of ‘threat’ and inflaming the grievances and anger that lead them to rally around him.” In her view, this requires “avoiding the type of ‘identity politics’ that stresses differences and creates a sense of ‘zero-sum’ competition between groups and instead emphasizing common values and interests.” Like Mark Lilla, Berman portrays identity politics as an obstacle to achieving the goals of liberal progressives.

As a black person living in the West, and a purported beneficiary of identitarianism, I feel compelled to take this a step further.

‘Identity politics’ means different things to different people. Personally, I like this characterization by Sonia Kruks, an Oberlin College politics professor, in her book Retrieving Experience: Subjectivity and Recognition in Feminist Politics:

What makes identity politics a significant departure from earlier, pre-identarian forms of the politics of recognition is its demand for recognition on the basis of the very grounds on which recognition has previously been denied: it is qua women, qua blacks, qua lesbians that groups demand recognition. The demand is not for inclusion within the fold of “universal humankind” on the basis of shared human attributes; nor is it for respect “in spite of” one’s differences. Rather, what is demanded is respect for oneself as different.

Add to this the view, common to postmodernist critical theory, that society revolves around various in-groups and out-groups (men, women, blacks, whites, cis, non-cis, etc.) and that these groups are defined in some fundamental, all-consuming way by power differentials, and this gives rise to a hierarchy of identities. The fundamental objective of left-wing identitarians is to strengthen the weaker groups while simultaneously weakening the strongest (whites, especially cishetero white males) to achieve a more ‘equitable’ distribution of power. So far, so good from my own self-interested point of view. I would much prefer to be the member of a powerful group than a powerless one. Question is, can identity politics deliver on this promise?

Evidence suggests that a group’s bargaining power is contingent on, among other things, the amount of resources – material and non-material – that it brings to the negotiating table. In light of this, feminism makes strategic sense. Women constitute roughly half the population of any given nation. In many Western countries, women slightly outnumber men. Thus, in terms of raw numbers alone, this ‘identity group’ possesses huge bargaining power. Another tactical advantage feminist identitarians have is that the people their demands are often addressed to, men, are inextricably linked to women via a variety of close personal relationships. The feminist actress Louise Brealey was on to something when she said: “I’d like every man who doesn’t call himself a feminist to explain to the women in his life why he doesn’t believe in equality for women.” Good luck with that guys!

No society can reproduce itself without the cooperation of its female members. True, men are necessary as well, but the point is no society can afford to turn on its women or deny them power if they insist on it for long and hard enough. All the addressees of their demands (males) can do is to negotiate a face-saving surrender. As Michael Lewis wrote in Home Game: an Accidental Guide to Fatherhood:

At some point in the last few decades, the American male sat down at the negotiating table with the American female and — let us be frank — got fleeced… Women may smile at a man pushing a baby stroller, but it is with the gentle condescension of a high officer of an army toward a village that surrendered without a fight.

In the long run, feminism is a very sensible power-achieving strategy for its supposed beneficiaries. But racial identitarianism, in comparison, is less promising.

Contrary to demographic scare stories disseminated by the far-right, black people don’t really hold that strong a hand in terms of numbers. While Western European nations like Germany and France don’t keep racial statistics, in the U.K. where I live – and which is arguably the most diverse country in all of Europe – ethnic minorities constitute just 13 percent of the population, with my group (blacks and mixed-black) making up under five percent. Moreover, an important factor that’s usually overlooked in discussions on race in Britain is how significantly European Union (E.U.) immigration has ‘whitened’ the country. Whites currently constitute 87 percent of the U.K. population, but this proportion will likely rise in the near future once a majority of the 3.8 million overwhelmingly-white European Union citizens living in the U.K. acquire British citizenship following Britain’s departure from the E.U. Most of these E.U. citizens are from Eastern European countries like Poland, my mother’s birthland, where people generally have a stronger sense of white identity and have more provincial views on race than the indigenous white-British population.

In 2016, Poland overtook India as the most common foreign country of birth for people living in the U.K., reflecting the changing nature of recent migration to Britain. Such are the realities that black Britons will have to come to terms with in the coming years. We currently only constitute one in 20 British citizens and that proportion is likely to shrink. In light of this, a political creed that, as Berman put it, “stresses difference and creates a sense of ‘zero-sum’ competition between groups” doesn’t seem like it’s in my best interests.

What about the promises of racial identitarians in America, where some projections indicate whites will constitute less than 50 percent of the population by 2045? Unfortunately, long-term population projections tend to assume a stable status quo not just in birth- and death-rates, but also in patterns of migration. However, those things are unstable and identitarians hoping to celebrate the end of white-majority America in less than 30 years time should be cautious. Especially if they are right about society as an arena of ongoing group struggles.

I can easily imagine a white-anxiety-driven coalition electing a U.S. Congress and President who wouldn’t shy away from passing immigration laws making it significantly easier for white Europeans to settle in America than migrants from other parts of the world. Apart from protesting such moves, there is little the left would be able to do to stop them were such a coalition to attain political power. And let’s not forget, it has already captured the Presidency. Such laws might not have enough impact to reverse demographic trends in America, but they could considerably delay the white-minority scenario that some of the left are eagerly awaiting.

Besides, even according to these projections, the racial segment I’m most interested in – America’s black population – is forecast to be almost exactly where it is today, at roughly 13 percent. So even by 2045, only 1 in 8 Americans will be black. It is the Hispanic population that is expected to expand from 18 percent to nearly 25 percent during the next 25 years or so – and as an article in the Washington Post pointed out earlier this year:

[T]he strict black/white binary of racial identity in the United States differs from the more nuanced racially-mixed narrative of Latin America, whose societies offered a form of ‘racial status mobility’ through intermarriage with Europeans.

A Pew Research study in 2017 showed high interracial marriage rates among Hispanics, leading to the fading of a ‘Hispanic’ identity over several generations. While almost 90 percent of newcomers to America from Spanish-speaking parts of the world identify as ‘Hispanic’, the number drops to 50 percent by the fourth-generation. Many descendants of Latin American (as well as Asian) immigrants eventually come to identify as ‘White’, which is why America today is 62 percent white when census respondents are forced to choose only one racial category, but 80 percent white when they can tick more than one box (e.g. Hispanic and white).

It is safe to assume that the people of Hispanic and Asian heritage who at least partially identify as white – and will do so in increasing numbers – are unlikely potential allies for black identitarians in a future America. So if African-Americans are going to remain a static 13 percent of the population, how is black identity politics going to help them?

Another difference between feminist identity politics and racial identity politics is that the rest of society does not always have strong personal, much less familial, ties to black folks, guaranteeing constant interaction. Unlike anti-feminist men, white people who refuse to accede to the demands of racial identitarians are unlikely to be punished by their nearest and dearest.

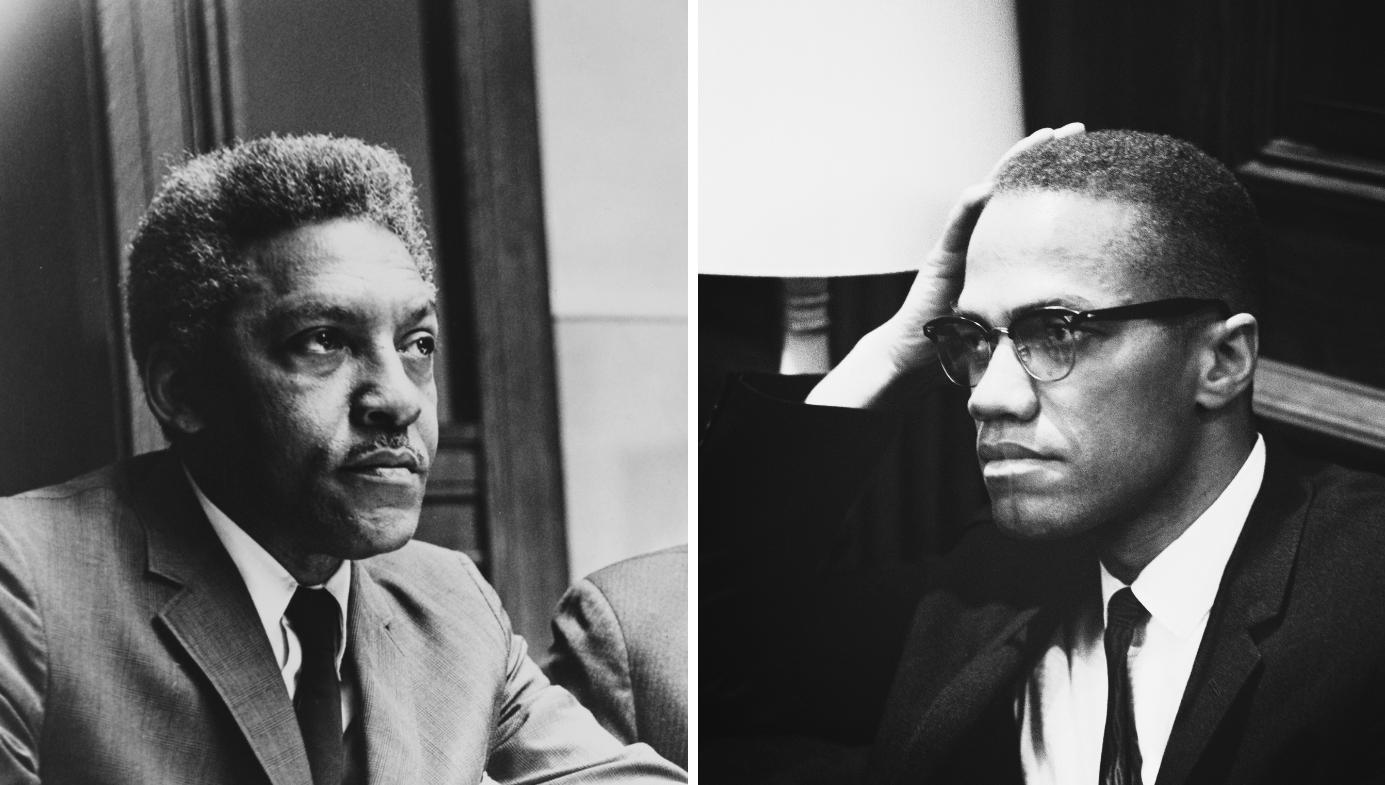

It is because he acknowledged this reality that Martin Luther King stressed non-violent resistance to Jim Crow laws. Commenting on Malcolm X in his autobiography, King wrote:

In his litany of articulating the despair of the Negro without offering any positive, creative alternative, I feel that Malcolm has done himself and our people a great disservice. Fiery, demagogic oratory in the black ghettos, urging Negros to arm themselves… can reap nothing but grief. In the event of a violent revolution, we would be sorely outnumbered. And when it was all over, the Negro would face the same unchanged conditions… the only difference being that his bitterness would be even more intense, his dis-enchantment even more abject. Thus, in purely practical as well as moral terms, the American Negro has no rational alternative to non-violence.

In his critique of black nationalism, MLK could be describing black identity politics today: a constant litany of grievances and bluster with no realistic strategy to eliminate the cause of those complaints.

So who exactly does benefit from black identity politics? I suppose it’s conceivable I might benefit, being a member of Britain’s tiny black middle class. As racial identitarians try and shame universities, media companies and tech firms for hiring too few black people I might find it easier to get a well-paid job. However, black architects or accountants are less likely to benefit. When did you last see a newspaper headline raising alarm bells about ‘Too few black accountants’? As for black plumbers, mechanics and bus-drivers, forget it.

No, the main beneficiaries of racial identity politics are the identitarians themselves. They are the ones making good money selling books encouraging black people to scapegoat white people for all their problems. They play to the unfortunate human weakness for blaming your problems on other people – something that’s also exploited by right-wing demagogues encouraging the white working class to blame immigrants for their problems.

Ironically, these snake-oil salesmen would not have achieved anything like the success they have without the complicity of guilty white liberals. As the African-American intellectual John McWhorther has pointed out, black identitarians like Ta Nehisi-Coates are “revered” as “priests” by white devotees of racial identity politics, who rush to pay homage and help spread the Gospel of anti-racism. Meanwhile, the negotiating position of black people is weakened by the day. Instead of reserving what was once a very effective tool at our disposal as a nuclear option – the stigmatizing power of the label ‘racist’ – identitarians are rendering it a blank bullet through overuse. Steven Bannon has said that he looks forward to the day when calling someone ‘racist’ has lost all power to stigamitize and he has no greater allies than racial identitarians and their guilty white devotees.

The day is fast approaching when mainstream white society will react to accusations of racism with yawns and shrugs. What will identitarians do then? Invent a new word that will magically possess the once mightily discrediting power that ‘racist’ did? Retreat fully into ethnic enclaves in Western countries? Raise black armies to take over the state?

Most probably, they’ll simply continue to live in their middle or upper-middle class neighbourhoods, mixing with other successful minority professionals and white liberals while working-class black folks bear the brunt of this sea change in their workplaces and racially-mixed or white-dominated working-class neighbourhoods. It is the African immigrant who will suffer, desperate to get to Europe or America to better his family’s future, yet facing the increasing hostility of white immigration officials and having to leap over ever-growing hurdles. Meanwhile, identitarians will continue selling books attacking ‘white supremacy’.

There must be a better way forward. In 2014, psychology professors Tamar Saguy and Nour Kteily conducted a fascinating study on how groups negotiate power among each other that points towards a more effective strategy. To be fair, it is worth noting their study confirmed one argument that left-wing identitarians often make, namely, that groups with power prefer not to discuss their power. They found that “high-power groups” ranging from Ashkenazi Jews in Israel, Muslims in Turkey and whites in the U.S. “preferred to focus [inter-group] encounters on topics emphasising cross-group commonalities, and to de-emphasise topics that bring to light power differences between the groups.”

In strong contrast, members of low-power groups preferred to discuss commonalities and power differences. In other words, blacks and other minorities want to discuss power differences in Western societies; whites would rather not, preferring to defuse tensions by emphasizing what we all have in common.

But another key finding in Saguy and Kteily’s study was that in response to strong moral arguments, high-power groups exhibited a readiness to address power differences, but only when they “perceived their group’s dominant position in the hierarchy as stable.” When they worried about “narrowing advantage” and potential personal losses, they demonstrated a strong resistance to addressing power differences.

This supports Sheri Berman’s analysis and shows how misguided it is for many on the left to continuously emphasize, and even gloat over, how soon whites will lose their majority advantage. All that does is make many whites less willing to address power inequalities, which is highly counter-productive for minorities. It’s that kind of talk that will lead to Trump winning a second term.

A smarter strategy would be to play down this perceived threat to whites. How? Saguy and Kteily suggest low-power groups emphasize working together with high-power groups “to achieve mutual gains” rather than signal their desire to “displace their [high-power] counterparts.” True, you won’t sell a lot of books or fire up a lot of progressives emphasizing cooperation and mutual gains; in fact, you will likely be met with many yawns and accusations that you’ve ‘sold out’. But to quote Martin Luther King again:

There is a concrete, real black power I believe in. I don’t believe in black separatism, I don’t believe in black power that would have racist overtones, but certainly if black power means the amassing of political and economic power in order to gain our just and legitimate goals, then we all believe in that.

This economic and political power will not be achieved via feisty rhetoric, empty bluster and antagonistic attitudes. It can only be achieved through smart strategic thinking. Identity politics is a road to nowhere for black people in the West.