History

Moral Panic, Then and Now

Boycotts, de-platforming and witch hunts do “succeed” in the narrow sense that they can ruin lives. But they don’t change anyone’s privately held opinions.

When my very Christian parents tried to throw away my 14-year-old sister’s heavy metal records, she ran away to her friend’s house. I cried for days. It felt like the end of everything. My sister would be gone forever. I would now live in what was referred to at the time as a “broken home.” I imagined that I’d be reunited with my sister in a few years—on the mean city streets after I’d been forced into a life of crime.

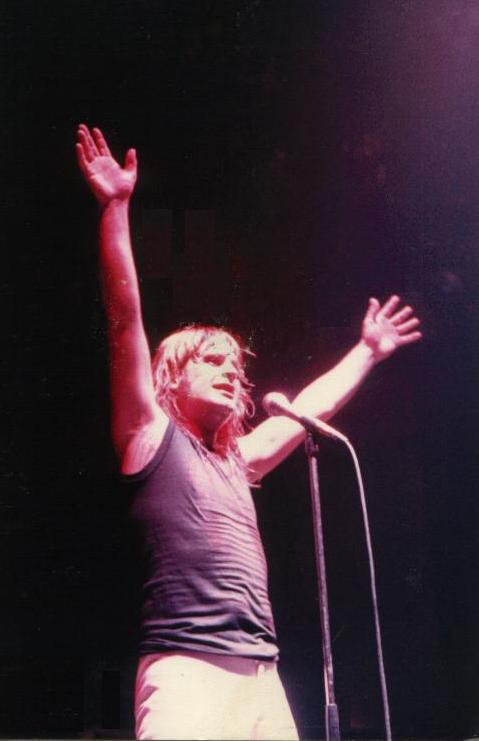

Both my parents and sister seemed to make good arguments. My mother and father tried to trash the records because they loved my sister, while my sister ran away because of her love for Dee Snyder. My parents wanted my sister to be safe. My sister wanted to express her individuality through music. My parents claimed that heavy metal was the cause of my sister’s rebellious behavior. My sister said that Judas Priest rocked, and elevated Ozzy Osbourne to secular sainthood. My parents thought my sister had fallen victim to satanic messages encoded in vinyl, while my sister believed my parents were enslaved to religious dogma printed in the Bible.

I remember the Bible studies and prayer groups well. There was a uniformity of belief and cause that united my parents and their pious peers. There was a collective smugness and sense of superiority that led members of the church to purge the culture (or what parts of the culture they could control) of dangerous and unholy influences. They wanted culture to be safer. Their targets: violence and overt sexuality in movies, music and video games.

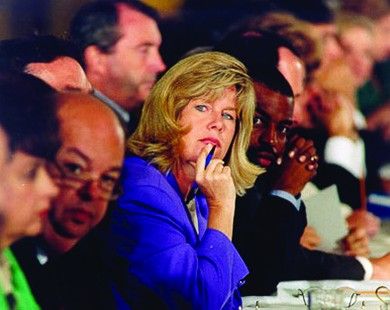

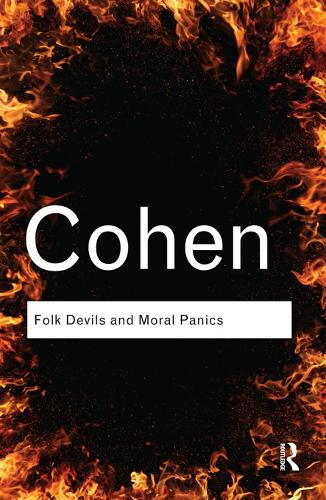

This all happened during a period of what sociologist Stanley Cohen called “moral panic”—the collective societal fear that some evil force (in this case, heavy metal) would destroy us all. In the eighties, many devout Christians protested and boycotted bands that featured what was then called “mature content.” Tipper Gore established the PMRC (Parental Music Resource Center) and formed unlikely alliances with evangelical conservative Christian organizations, such as James Dobson’s Focus On the Family, to keep heavy metal and rap music away from impressionable young ears. They even drafted a list called the “Filthy Fifteen,” which documented the worst offenders. (The list included Prince, Madonna and Cyndi Lauper, because her song She Bop supposedly glorified masturbation.)

This all seems quaint now. But innocent people were swept up in these campaigns. (Punk icon Jello Biafra, for instance, was arrested on obscenity charges.) Moreover, the culture wars over music fed the satanic panic of the late 1980s and early 1990s. Bolstered by the bogus science of “recovered memories,” psychologists coerced children into lurid claims of ritualized abuse. Falsely accused people went to prison. Some only got out recently. Some did not survive.

Writing in The Atlantic last year, Emily Yoffe made a compelling case that the trauma-focused approach of today’s therapists and activists evokes the recovered-memory hysteria of the 1980s; and that claims of a “rape culture” on campuses echoes the satanic panic that drove my sister out of our home. The piece echoed an equally brave 2014 article for The Nation, by JoAnn Wypijewski, who wrote: “These panics have shared features. Sex figures as a preternatural danger, emotion swamps reason, monsters abound, and protection demands any sacrifice.”

Of course, sexual harassment and assault are very real and all-too-common problems (unlike satanic child-abuse cults). But this is precisely why we must resist the spread of dubious, and often debunked, statistics that purport to show an epidemic of rape (such as those appearing to indicate that it’s just as dangerous for a young woman to go to university in North America as it is for her to live in a war-torn country).

During the time of satanic panic, fear was spread by the PMRC, by politicians, by Geraldo and Oprah, and by well-meaning therapists and activists. The campus rape panic, similarly, is fed by the U.S. Department of Education (with its Title IX guidance of 2011), by Twitter hashtag campaigns, and by those same well-meaning therapists and activists.

As has been widely noted by other Quillette writers, many of today’s progressive activists have sacrificed classical liberal values such as freedom of speech and due process in their zeal to create safe spaces for all. While harboring nothing but disdain for social-conservative Christian values, they actually exhibit the very same collective fear, and the very same obsession with virtue and spiritual purity, that animated the puritanical Bible study set I grew up with. They protest controversial speakers and artists—just like Tipper Gore did; and seek to get musical acts banned from festivals. They want culture to be safer. And their targets would be instantly recognizable to my parents and their church-going friends: violence and unashamed sexuality.

Some activists have gone so far as to prevent innovative musical artists from entering entire countries because of problematic content produced in the past. The Australian activist organization Collective Shout, for instance, lobbied successfully to ban Tyler, the Creator from entering Australia because his music contained references to rape and other misogynistic material. Its petition read:

The messages propogated [sic] in these lyrics pose particular risk to the Australian community by conveying the message that interpersonal conflict might be legitimately resolved through violence. Unfortunately this message still enjoys resonance in significant parts of our society which heightens the risk posed to women and children of his entry.

Compare those words to these:

Racial and sexual epithets, whether screamed across a street or camouflaged by the rhythms of a song, turn people into objects less than human—easier to degrade, easier to violate, easier to destroy.

That’s from Tipper Gore in 1990, when she was railing against rapper Ice-T and his contemporaries. Both Collective Shout and Gore relied on the idea that an artist’s choice of language can lead to violence. And both statements play on the idea that listeners are weak-minded and impressionable.

The right-left pro-censorship alliance that Gore formed three decades ago has its modern equivalent in the Twitter era. Right-wing men’s rights advocates and hyper-progressives found common cause in an online shaming campaign targeting Canadian feminist Meghan Murphy, for instance, after she dared suggest that women born into their female bodies might have reason to see themselves differently from those born with penises. And the recent de-platforming of second-wave feminist icon Germaine Greer on the basis of perceived transphobia would be met with gleeful applause by stridently conservative Australians as much as by stridently progressive gender-studies post-docs. The tactics used by right-wing Twitter trolls such as Mike Cernovich to get James Gunn fired from Disney are identical to those used by the left to get Twitter troll Godfrey Elfwick de-platformed. Their crime was the same: tweeting controversial jokes.

But while all forms of social panic tend to resemble one another, there are some stark differences between now and then. For one thing, young people today seem more naturally censorious and culturally conservative than their parents. Peace, love, freedom, and experimentation have been replaced by an obsession with emotional safety. Today’s young men and young women seem scared to death of each other. The LGBT community has fractured into its alphabetic constituent parts. And racial tensions are fed by a steady diet of online microaggressions. Everyone feels at risk, despite the fact the free world has never been safer.

Of course, moral panics are not based on facts but fears. In Stanley Cohen’s 2002 introduction to Folk Devils and Moral Panics, he writes that in moral panics, “the prohibitionist model of the ‘slippery slope’ is common … [and] crusades in favor of censorship are more likely to be driven by organized groups with ongoing agendas.” They are driven by organized groups, yes, but they are facilitated by well-meaning, ill-informed actors such as activists, therapists, and law enforcement officers. From the censorship of comic books, to video games, to music, we’ve known about the agendas of these special interests for a very long time. So why do we keep falling for it?

Moreover, there seems to be more hypocrisy at play in 2018 than there was during the moral panics of the 1980s. Many Christians who embraced Tipper Gore’s campaign truly were sincere anti-sex and anti-violence crusaders. But the world that people inhabit in 2018 is at once hyper-explicit and puritanical. In one browser tab, we’re typing about how words are violence, while in the other tab, we’re engaging in malicious gossip that could ruin someone’s career.

A feverish approach that seeks to sanitize culture is harmful but is also futile. Forbidding people from consuming content can often serve to make that content more desirable to consumers, something similar to the Streisand Effect. This phenomenon is named after Barbra Streisand’s futile attempt to keep photos of her Malibu mansion off of the internet. The harder she tried to stop people from posting photos, the more photos appeared. Paternalistically making music and art “forbidden content” makes it sexier, and elevates its status. The PMRC’s Filthy Fifteen is chockfull of rock and roll classics that went on to make millions. My parents’ disdain for heavy metal certainly did not make my sister pop Perry Como into her Walkman – she just rocked harder. Fans and free speech advocates rally around Tyler, the Creator today now more than ever.

Boycotts, de-platforming and witch hunts do “succeed” in the narrow sense that they can ruin lives. But they don’t change anyone’s privately held opinions. Nor do they ever stop artists from producing controversial art. In the end, free speech and true art always prevail as the antidote to moral panic.

I’m happy to report that my own family survived the heyday of satanic panic with only minor grievances to show for the experience. My sister came back, and our home was not “broken” for long. Everyone today is relatively happy and mostly well adjusted.

Yet the other day I asked them about the heavy metal incident. My sister still feels the sting of betrayal, and the trauma of being mistrusted by my parents. Everyone involved still loves each other, but my parents still blame the “dark music” and my sister still blames my parents. For my sister, it was a defining moment of her personal narrative, something she survived. For my parents, it was a minor incident they hadn’t thought about for years. In these recollections, there is a very small glimpse of a larger psychological phenomenon that applies to moral panics. Those who dole out justice move on to other things and their memories fade, while the effects of that justice linger in those they have judged and sentenced. Not everyone makes it out of a moral panic as healthy and intact as my family did. Some don’t even escape with their lives. I suspect one of the reasons moral panics keep happening is that all of us are very good at simply forgetting.