Art and Culture

Britain's Populist Revolt

Britain has produced a Brexit debate that is utterly dry, sterile, and completely lacking in imagination.

More than two years have passed since Britain voted for Brexit. Ever since that moment, the vote to leave the European Union has routinely been framed as an aberration; a radical departure from ‘normal’ life. Countless journalists, scholars, and celebrities have lined up to offer their diagnosis of what caused this apparent moment of madness among the electorate. Russia-backed social media accounts. Shady big tech firms like Cambridge Analytica. Austerity. The malign influence of populist ‘Brexiteers’ like Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage. The Brexit campaign exceeding its legal spending limit. Or a much-debated claim, written on the side of a bus, that Brexit would allow Britain to redirect its millions of pounds worth of contributions to the EU into its own creaking health service. Typical is a recent piece by a (British) columnist in the New York Times who argues: “Britain is in this mess principally because the Brexiteers—led largely by Mr. Johnson—sold the country a series of lies in the lead up to the June 2016 referendum.”

Britain has produced a Brexit debate that is utterly dry, sterile, and completely lacking in imagination. Much of the commentary has shared three features: an exclusive focus on incredibly short-term factors that apparently proved decisive; a clear and concerted attempt to try and delegitimize the result by implying that either voters were duped or that the Leave campaign was crooked; and absolutely no engagement whatsoever with the growing pile of evidence that we now have on why people actually voted for Brexit. Far from staging an irrational outburst, most Leavers shared a clear and coherent outlook and had formed their views long before the campaign even began.

What seems remarkable to me is the sheer amount of energy that has been devoted to undermining or overturning the result versus that which has been devoted to exploring what led to this moment in the first place. There is no doubt that some of the short-term factors mentioned above were important. Brexit campaigners did make misleading claims and did spend more money than they should have. But this was also a campaign that saw the pro-Remain Prime Minister David Cameron suggest that Brexit might trigger World War Three, London’s elite prophesize about financial Armageddon, and political and economic leaders from across the globe descend on Britain to issue similarly dire warnings, including President Obama. In short, in the history of political campaigns this one was definitely not an example of best practice.

Perhaps I was woefully naïve, but in the days after the referendum I felt excited; anxious about the short-term fallout but excited about the long-overdue debate that I assumed was en route; a national focus on addressing the divides, inequalities, and grievances that had led to this moment. Perhaps this was what Britain needed, I thought, a radical shock that would throw light on what had been simmering beneath the surface for decades. I also assumed that my academic colleagues would be with me. But the debate never arrived.

Today, looking back, I see that most people never really had an interest in exploring what underpinned Brexit. To many on the liberal Left, Brexit is to be opposed, not understood. There has been no conversation about why people voted for Brexit because conversations require a reply. One side has spoken but, with a few rare exceptions, almost nobody on the other side has thought about what such a reply might be.

Instead, they have sought to overturn it, force a re-run of the vote or water down Brexit to such an extent that it is basically the status quo. Few have seriously considered what the political effects of these outcomes would be. One prominent journalist recently tweeted that reversing Brexit would be a “hammer blow to Western populist-nationalism.” But I suspect that it would be quite the opposite; an erosion of public trust, hardened social divides, and the political equivalent of pouring gasoline on a populist fire.

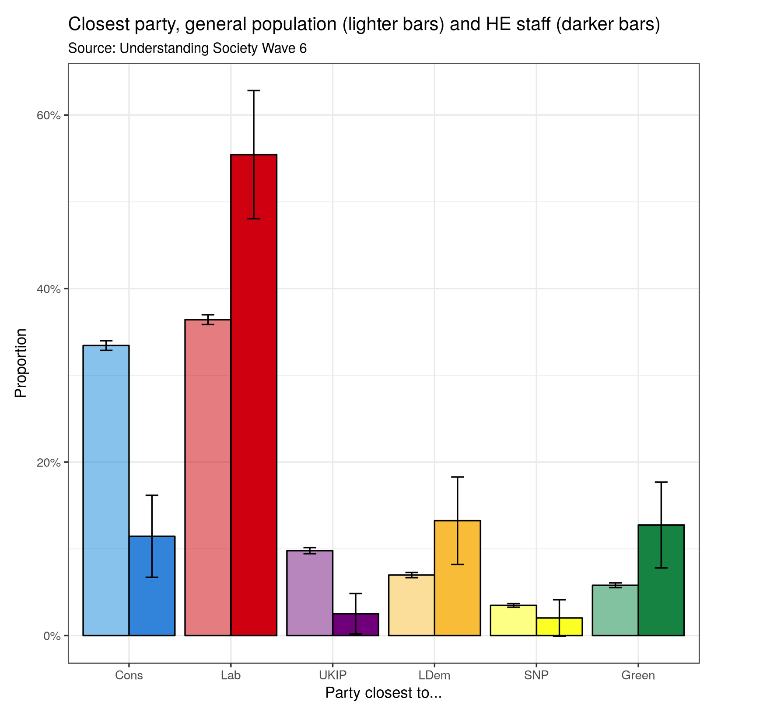

This has also been true in the academy where quite a few scholars, especially on social media, have morphed into anti-Brexit campaigners. This is not surprising given the extent of political orthodoxy in UK academe, as shown below. As in the US, with academics overwhelmingly more likely to vote for left-wing and ultra-liberal parties, it is unsurprising to find that the search for truth and the exploration of diversity in all its forms has at times found itself relegated behind Jean Monnet professors gleefully hailing any piece of news that looks bad for Britain. I’m pragmatic on Brexit; it’s happened and so we should work with it. But when I share this view I am often greeted by what I call ‘The Silence.’ Those who have gone even further by admitting to having actually voted for Brexit have described the reaction from colleagues as if they had “just admitted to poisoning the neighbour’s dog.” If you’re not opposing Brexit—or at least endorsing those who are—you are a marked card. Viewpoint diversity? Not so much.

Perhaps this is part of the reason why, in the wider debate, myths about the Brexit vote have flourished. You don’t have to spend too long on the Westminster circuit or scanning prominent Twitter accounts to come across one of several lazy narratives: voters were too stupid to know what they were voting for; Brexit was an irrational backlash; it was a protest rather than an instrumental act; a by-product of fake news and misinformation rather than a conscious repudiation of the status quo. The total lack of serious reflection was brought home to me when David Cameron, who had resigned only hours after the vote, reappeared six months later to share his conclusion: Brexit reflected “a movement of unhappiness.” How strange, I thought, because most of the Brexiteers I knew were bloody delighted.

Such reactions are unsurprising. After all, the referendum marked the first occasion in Britain’s history when the culturally liberal middle-class, which orbits London and the university towns, had lost. Until this point, the advocates of double liberalism—a globalized economy accompanied by a highly liberal immigration policy—had gotten all they had wanted. Business got a continuing influx of mass cheap labour that fed a consumption-driven growth model that not only removed incentives for investing in training but exacerbated divides between the high and low-skilled. The liberal middle-class got economic benefits alongside Polish cleaners and membership of the dominant value set but became increasingly detached from the ‘left behind.’ Even though political scientists had torn apart the ‘protest thesis’ two decades earlier, showing how people who rebel against the liberal consensus also hold clear and consistent preferences, to many of the winners who now suddenly felt like losers the idea that this was just an irrational backlash seemed like the easiest and most comforting explanation.

Many found further solace in a revival of elite theory, joining a long tradition of voicing suspicion of, if not open hostility toward, the mass public that can be traced back to Ancient Greece. The EU is simply too complex for ordinary people to understand. Elites know better. Apathy might be a good thing after all. But it has now gotten to the point where some jump on anything that goes wrong in Britain as a vindication of their anti-Brexit stance. A bank relocates workers to Frankfurt? Good! Economic growth down? Told you so! Food is a bit more expensive? Tough luck! I’ve grown tired of watching my fellow citizens cheer anything that looks even vaguely like national decline.

Recently, I found myself at a dinner in the City listening to financial types laugh away about how Brexit will eventually screw over the very people who voted for it. Only a few hours earlier they had asked why people across the West are rebelling against the mainstream and levels of distrust are at an all-time high. On the way home I felt thoroughly depressed, wondering what had happened to the common good, to the people who are interested in forging consensus and fixing the social contract.

Evidence on who Leavers are has been traded for comfort blankets. Recently, a prominent liberal politician suggested that Brexit was driven by pensioners who longed for a world where “faces were white.” References to angry old white men are never far away. Arguments that are implicitly about generational change are popular on the liberal Left because they do not require people to engage with the actual grievances. The world becomes a progressive conveyer belt; intolerant old men will soon die; tolerant liberals will soon rise.

What gets lost in these debates is the actual evidence. Contrary to rumour, Brexit was supported by a broad and fairly diverse coalition of voters; large numbers of affluent conservatives; one in three of Britain’s black and ethnic minority voters; almost half of 25-49 year-olds; one in two women; one in four graduates; and 40 percent of voters in the Greater London area.1 Brexit appealed to white pensioners in England’s declining seaside towns but it also won majority support in highly ethnically diverse areas like Birmingham, Luton, and Slough. You don’t hear much about these groups in the media vox pops in retirement homes and working men’s clubs in poverty-stricken communities. Had these other groups that are routinely written out of the debate not voted Leave then Britain would probably still be in the EU.

Nor did these voters suddenly convert to Brexit during the campaign, which is another common misconception. One point that is routinely ignored is that British support for radically reforming or exiting the EU was widespread long before the referendum even began. Britain’s National Centre for Social Research recently pointed out that levels of British support for leaving the EU or radically reducing the EU’s power “have been consistently above 50 percent for a little over 20 years.” This is what the ‘short-termists’ cannot explain. If Brexit was an aberration, a by-product of wrongdoing, then why were so many people unhappy with this relationship long before the Great Recession, or the arrival of Twitter or Facebook? The currents that led to this seismic moment were decades in the making.

Few political campaigners and journalists read history. Perhaps one reason why so many were caught off guard by the political revolts of 2016 is that they increasingly lack a strong background in history or the hard sciences, which might otherwise have led them to question the relative importance of short-term factors, electoral forecasts, and dodgy data modelling. Had they taken a longer-term view, it would have been clear that the ‘fundamentals’ favoured Leave and had been baked in long ago.

To begin with, you simply cannot make sense of Brexit without being aware of a British—or more specifically English—national identity that, ever since the sixteenth century, had been forged by Protestantism, fear of the ‘Catholic Other’ across the Channel, and popular belief in a providential destiny, shaped by successive wars with European powers, a jingoistic press, and experience of Empire. “This was how it was with the British after 1707,” noted the historian Linda Colley in her seminal book Britons. “They came to define themselves as a single people not because of any political or cultural consensus at home, but rather in reaction to the Other beyond their shores.”2

The nature of this national identity was the first in-built advantage for Leave. ‘Englishness,’ or feeling very strongly attached to the nation, became a key tributary of the Leave vote. Whereas 64 percent of people who felt ‘English not British’ saw Britain’s membership of the EU as a ‘bad thing,’ among those who felt ‘British not English’ this crashed to 28 percent. The more English people felt the more likely that they would support Brexit.

It was, therefore, no surprise when in later years most people simply never developed an affective attachment to the idea of European integration. The British had perhaps always been suspicious of power hierarchies that felt remote and lacking in democratic accountability. But they had also been wary of identities that claimed to supersede the nation. Dreams of a pan-European ‘demos’ had only ever appealed to a small number of cosmopolitan liberals. “We are one people in Europe,” proclaimed Natalie Nougayrède in the left-wing Guardian newspaper during the 2016 referendum. Yet the reality for most voters was altogether different. When asked how they thought of their identity, between 1992 and 2016 an average of 62 percent of Brits said they were ‘British only.’ Only 6 percent prioritized a ‘European’ identity.

Of course, in 1975, a majority of British voters had voted to endorse their nation’s membership of what was then called the European Community. But this had been rooted in economic pragmatism not affective attachment. Integration offered an opportunity to remedy Britain’s status as the ‘sick man of Europe,’ a nation that was beset by economic problems. There had never been much desire for taking the relationship further. As two scholars noted at the time, British support for joining Europe had been wide but never deep.

Over the next four decades, Britain’s long and entrenched tradition of scepticism toward Europe remained clearly visible. Between 1992 and 2015, an average of 52 percent of people either wanted to leave the EU or stay in but significantly reduce its powers, though this jumped to 65 percent in the immediate years running up to the 2016 vote. Throughout the early years of the twenty-first century, never more than 19 percent of people wanted to strengthen their country’s relationship with the EU.

These topline figures obviously hide variations. Consistently, it was the working-class, older voters, and those with few qualifications who were the most likely to oppose Britain’s EU membership, not least because of their socially conservative and, in some cases, authoritarian values. But as the 2016 referendum neared, support for leaving also increased among graduates and the middle-class, albeit not to the same levels.

Crucially, as Britain headed into the twenty-first century, the nature of this scepticism also changed in important ways. In the 1990s, debates about the EU had focused on law and sovereignty, issues that were of particular concern to middle-class Conservatives. But by the 2000s, the audience for anti-EU campaigns expanded massively. At the heart of this was immigration.

Unlike most other governing parties in the EU, in 2004 New Labour, led by Tony Blair, decided that it would open Britain’s labour market to migrant workers from the so-called ‘A8’ states like Estonia and Poland that had just joined the EU. Immigration into Britain had already been on the rise, but now it reached new heights. Between 1991 and 1995, the annual average level of net migration (i.e. the number of people coming in minus the number leaving) had been just 37,000. Between 2012 and 2016 it averaged 256,000.

On one level, this large-scale migration exacerbated growing divides between high-skilled and low-skilled workers. Why would businesses invest in training, new technology, and workplace innovation when they could raise output by hiring low-wage workers and enjoy an abundance of cheap labour? On another, it fuelled widespread public concern about how rapid and often unprecedented demographic change was radically transforming communities.

Even before the Great Recession and austerity, between 1997 and 2007, the percentage of people that ranked immigration as one of the top issues facing Britain rocketed from 4 to 46 percent. By the time of the 2016 referendum, the issue had dominated the list of people’s priorities for more than a decade. Nearly eight in ten people wanted to see immigration reduced.

The issue became entwined with the EU, not least because voters had realised that much of the influx was due to the ‘free movement’ into Britain of EU nationals from Central and Eastern Europe, and later southern EU states like Italy and Spain. Even before senior Leave campaigners started to target immigration, nearly half of the population had concluded that being in the EU was ‘undermining Britain’s distinctive identity.’ Only 31 percent disagreed. Many now looked at the EU as an engine of ever-accelerating demographic and cultural change and with no apparent end in sight.

One person who would not have been surprised was the academic Lauren McLaren. More than a decade before the 2016 referendum, McLaren had demonstrated that public hostility toward the European project was not only powered by people’s worries about the economy. They also felt anxious about how the sudden influx challenged established norms and ways of life. “People do not necessarily calculate the costs and benefits of the EU to their own lives when thinking about issues of European integration,” concluded McLaren, “but instead are ultimately concerned about problems related to the degradation of the nation-state.”3

By the time of the referendum, however, the people were not sure who to trust on immigration. Both of Britain’s main parties had misled the electorate, either by claiming that immigration would be much lower than it turned out to be, or promising to reduce net migration “from the hundreds of thousands to the tens of thousands” (which most voters knew was impossible so long as Britain remained in the EU and subject to the freedom of movement principle). Immigration had historically been owned by the Conservative Party. But by 2016, when voters were asked who they trusted on the issue, the most popular answers were the right-wing UK Independence Party, ‘none of them,’ or ‘don’t know.’ Worryingly, these unresolved grievances were also having deeper effects; researchers found that the consistent failure to address people’s concerns was eroding overall trust in the political system.

As the referendum neared, this sense of threat was further amplified. A major refugee crisis erupted on the European continent while EU member states were openly and bitterly divided over the issue. Such events coincided with major Islamist terrorist attacks, notably in France, that in 2015 alone left nearly 150 dead and more than 350 injured. Suicide bombings would follow in Brussels. More than half of Britain’s population drew a straight line from the refugee crisis to terrorism, believing that the former would increase the latter. To many voters, such events not only entrenched a view that the EU could not be trusted to protect their borders, security, and way of life, but also a belief that ‘the risk’ lay less with Brexit than staying in the club.

Long before they had even looked at a campaign leaflet, therefore, many voters had come to share what social psychologist Karen Stenner has referred to as a feeling of “normative threat”; that sudden or fundamental changes in the surrounding world threaten an established order, a system of oneness or sameness that makes ‘us’ an ‘us.’4 As Stenner showed, when such threats are seen to challenge a wider community they trigger a sharp backlash from citizens who wish to defend not only themselves but the wider group.

In Britain, however, things took a different turn, at least initially. Instead of staging a backlash, the people who felt most threatened hunkered down. During the 2000s, many working-class voters had started to drift into apathy, losing faith in politics. This was the canary in the Brexit coalmine. In more northern and industrial communities, working-class voters provided isolated pockets of support to a small far-Right party, but most simply stopped voting altogether. Debates about turnout routinely focus on differences between the young and old but many observers missed a more important gap in turnout among the different social classes.

One person who had noticed was the political scientist Oliver Heath, who noted that until the 1980s there had been little difference in the rates of turnout among the working-class and middle-class (less than 5 points). Yet, by 2010, this gap had widened considerably to 19 points, which made it just as significant as the difference in turnout between young and old. Whereas in earlier years the working-class and middle-class had been divided on who to vote for, now they were divided on whether to bother voting at all.5

Many of these voters opposed the liberal consensus and felt excluded from the political conversation. They had a point. Between 1964 and 2015, the percentage of politicians in Westminster who had worked in manual jobs crashed from 37 to just 3 percent, while more recent research has shown how the rise of ‘careerist’ politicians, particularly in the Labour Party, lowered the amount of attention going to working-class interests. Meanwhile, the numbers that had been elected after working in politics or in London reached record heights. Such findings leant credibility to the perception of a political class that had become increasingly insular and detached from ordinary voters.6 Before the referendum even got underway, nearly 40 percent of working-class voters agreed that “people like me have no say in government.”

Between 2012 and 2016, many of these voters were then mobilized by the populist UK Independence Party, which many in the media wrote off as an ephemeral protest party. Despite having few resources, the party quickly won over a coalition of blue-collar workers and social conservatives who felt left out or left behind, not only in an economic sense but also by the values that had come to dominate Britain. They came from different backgrounds but shared strong opposition to EU membership, distrust of the main parties, and a desire to reform immigration. They also had a lot in common with those on the Left; they agreed that business takes advantage of ordinary people, that there is one law for the rich and another for the poor, and that workers are not getting their fair share of the nation’s wealth.

These concerns then came more fully into view as Britain headed into 2016. Shortly before the vote, the EU surveyed people across Europe and the findings underline how truly remarkable it is that so few people saw Brexit coming. The British were among the most positive about their own economy but among the most pessimistic about Europe’s economy (only 25 percent thought it was “good”). They were less likely than average to think that Europe’s would improve (only 18 percent thought so) and were almost the least likely of all to think that the “EU has sufficient power and tools to defend the economic interests of Europe in the global economy.”

The British were also the most likely of all to feel worried about terrorism and, when asked what the EU meant to them personally, were more likely than average to say “not enough control at [the EU’s] external borders” and among the most likely of all to say “loss of our cultural identity.” They worried about the democratic deficit in the EU—the distant institutions and perceived lack of democratic accountability—another issue that was totally ignored by the Remain campaign. They were more satisfied than most with their own democracy, but among the least satisfied with how democracy works in the EU. Long before Leavers asked them to “Take Back Control,” the British were already alongside the Greeks as being the least likely of all to trust the European Parliament. (Only 26 percent did.) More than half felt that their voice counted in their own democracy, but only one in three felt that it counted in the EU. And they were generally pessimistic about where things seemed to be heading in the EU. They were more likely than average to think that the quality of life in their own country was good, but they were among the most likely to think that the quality of life in the EU was bad. Only 17 percent felt that the EU was moving in the right direction, which fell to 14 percent among the working-class and 12 percent among pensioners.

I could go on. The Brits were the least likely to hold a positive image of the EU; the least optimistic about the future of the EU; and, though few observers noticed at the time, were only behind the Cypriots as the most likely to believe that their country “could better face the future outside of the EU.” Given such findings, one might ask not why Leave won the referendum but why it only attracted 52 percent of the vote.

The idea that those who went on to vote for Brexit were dispossessed white workers who live in fading seaside towns made for good copy but it was deeply misleading. Some Leavers certainly felt economically left behind, but many did not. Research has since shown that three groups were key to the Brexit vote:

- Left Behind Leavers, who were working-class, struggling financially, almost never had a degree, were in their forties or fifties and most of whom did not identify with the main parties or supported the UK Independence Party.

- Blue-Collar Pensioners, who were also working-class but retired, and so less likely to be struggling financially and tended to vote for Conservative.

- Affluent Eurosceptics, who were much less likely to identify as working-class, more affluent, more likely to have a degree and tended to vote Conservative. While we hear much about the first two groups we have heard very little about the third.7

And contrary to the claim that Leavers did not know what they were voting for, were misled, or engaged in an irrational backlash, an array of work has now shown how they shared clear and coherent preferences. Foremost, they wanted their nation state to have greater control over the laws that affect their daily lives and immigration to be reduced, which they felt could simply not happen so long as Britain remained in the EU.

Here are just a few findings from a literature that tells a remarkably consistent story: people who felt unhappy with how democracy works in the EU and who felt that immigration was having negative effects on Britain’s economy, culture, and welfare state were significantly more likely to back Brexit; people who felt that being in the EU had undermined national independence and identity and who felt that on balance immigration had been bad for Britain were more likely to back Leave; when Leavers were asked to describe their concerns in their own words the two most popular were “sovereignty” and “immigration”; when another large-survey asked Leavers to identify their reasons for wanting out of the EU, the most popular by far were “the principle that decisions about the UK should be taken in the UK,” and leaving “offered the best chance to regain control over immigration and borders.” Another concluded that people who felt that the EU undermined Britain’s distinctive identity and wanted to lower immigration were the most likely to back Brexit; and another found that those who felt anxious over immigration and believed they had been left behind relative to others in society were less likely to see Brexit as a risk and more likely to back Leave. A research institute at Oxford also asked Leavers to reflect on their rationale; the most popular response was “to regain control over EU immigration” followed by “I didn’t want the EU to have any role in UK law-making.” And contrary to the claim that Leavers were simply engaging in an irrational backlash against the Establishment, the motive “to teach British politicians a lesson” had (by far) the lowest ranking.

The rationale, therefore, was completely clear and coherent; to have more influence over the decisions that affect daily life and to lower, or at least have more control, over the levels of immigration into Britain.

Clearly, such attitudes reflect how a deeper values divide had been rumbling beneath British politics for many years, if not decades, as shown by the finding that many (though not all) of those who voted for Brexit tended to support capital punishment, stiffer sentences for criminals, and felt that social liberalism had gone too far. Though some journalists would later contend that voters were swayed by misleading economic data or social media campaigns, the reality is that Brexit was a natural extension of their pre-existing values; a vote to tip the scales back toward order, stability, and group conformity, and an attempt to defend the wider community that was seen to be under threat. Not every Leaver felt this way, but many did. This is why, though controversial, the anti-EU slogans of “Take Back Control” and “Breaking Point” (a reference to immigration and the refugee crisis) were not only emotionally resonant but more in tune with what was occupying the minds of voters—and had been for some time.

Remainers did not even try to win these sceptics over. Instead, they focused almost exclusively on a narrative that was rooted in rational choice—transactional and incredibly dry arguments about economic self-interest. It’s hard to make such a case to workers who had often not had a pay rise in over a decade or affluent social conservatives who cared little about the markets but worried intensely about flag, faith, and family. Remainers focused exclusively on the internal risk of Brexit while failing to recognize the fact that many voters were thinking about the external risks and threats that came with being in the EU. When it came to Brexit, 70 percent of Leavers felt that exiting the EU would be ‘safe’ while only 23 percent saw it as a risk. But when it came to remaining in the EU, 76 percent felt that was a risk while 17 percent felt it was safe. This was the big miscalculation.

All revolts are symptoms of deeper currents. The 2016 referendum offered an opportunity for people to express their view about EU membership, but this always looked set to become an outlet for more fundamental divides in British society that had long been present and will be with us for some time yet. Against this backdrop, and putting the more immediate negotiations over Brexit to one side, Britain faces many challenges but two are especially key.

The first is how to resolve the deep value divides that found their full expression during the 2016 referendum. These were exacerbated by a general election that followed less than one year later, and which provided further evidence of a possible long-term realignment. While the (now clearly pro-Brexit) Conservative Party hoovered up more working-class voters, non-graduates and former UK Independence Party voters, the more radically left-wing Labour Party made its strongest advances among the liberal middle-class, millennial graduates, and in pro-Remain districts. This value divide has become far more central to explaining electoral behaviour than social class and could yet force a more radical realignment of British politics.

A rapprochement seems unlikely, at least in the short-term. Consider what Leavers and Remainers want Britain to prioritise in the coming years. Leavers say Brexit, sharply reducing immigration, curbing the amount spent on overseas aid, and strengthening the armed forces. Remainers say build more affordable homes, raise taxes on high earners, increase the minimum wage, and abolish tuition fees. The only point of consensus is that both want to increase funding for the National Health Service.

A second challenge is to deliver a meaningful reply to the grievances that caused Brexit in the first place, not only through the current negotiations with the EU but also in domestic policy. Radical reform of our political and economic settlement has to be on the cards, as should an entirely new policy on immigration. Today, we are talking a great deal about how to ensure a continuation of the status quo rather than how to remedy the problems that led so many to demand that it be radically changed. We talk much about trade deals but little about the wider imbalance within our economy. We talk a lot about London but little about coastal, northern, or rural Britain, where in the end the Brexit vote was strongest. And we talk much about how to start a new centrist ‘anti-Brexit’ party but little about how existing political vehicles can adapt to better represent all segments of our society. It seems to me at least that unless we start to genuinely talk about these things then a few years from now we may well find ourselves back where we started.

References and Notes:

1 Unless otherwise stated, data is drawn from Harold Clarke, Matthew Goodwin and Paul Whiteley (2017) Brexit: Why Britain Voted to Leave the European Union, Cambridge University Press

2 Linda Colley (1992) Britons: Forging the Nation 1707-1837, New Haven: Yale University Press, pp.5-6

3 Lauren M. McLaren (2002) ‘Public Support for the European Union: cost/benefit analysis or perceived cultural threat?’, Journal of Politics 64.2, pp. 551-566

4 Karen Stenner (2005) The Authoritarian Dynamic. Cambridge University Press, 2005.

5 Oliver Heath (2016) Policy Alienation, Social Alienation and Working-Class Abstention in Britain, 1964-2010’, British Journal of Political Science (Early view online)

6 House of Commons Library Briefing Paper (2016) Social Background of MPs 1979-2017, London: House of Commons Library

7 National Centre for Social Research (2016) Understanding the Leave Vote. Available online: http://natcen.ac.uk/our-research/research/understanding-the-leave-vote/ (accessed June 15 2018).