Art and Culture

Reclaiming Work as a Virtue

Somewhere along the way, many of the intellectual classes stopped believing in work as essential to survival.

My father taught me a simple lesson: when the alarm clock goes off, you get out of bed, have a shave, wash yourself, put your clothes on and go to work. You’ve got to be resilient and you’ve got to be focused on what you want to achieve.

Dad believed the measure of a person was whether or not they were a worker. He believed that working was a virtue. So do I.

My father was Bundjalung and my mother Gumbaynggirr, two of the hundreds of first nations that existed across Australia before British colonisation. My Bundjalung ancestors had their first contact with white settlers in the early 1800s who came looking for grazing land. Like so many indigenous peoples across the world, this early contact included killings. But the initial hostilities gave way to a compromise with both sides showing a marked level of pragmatism. The settlers set up their sheep, later cattle, station and my ancestors lived and worked there, maintaining a good relationship with the station owners to this day.

My grandfather worked as a labourer all his life, hard, dirty work that didn’t pay much. Every day he got up, went to work and brought the money home for his family. Dad, my aunts and uncles grew up thinking that was normal. When Dad left school, he started working as an unskilled labourer too and in time became a skilled grader driver with better pay and opportunities. Until his seventies, he got up early every morning, went to work and brought the money home for his family. My siblings and I grew up thinking that was normal. And when we left school we also got jobs; some even went to university. Our kids thought that was normal and did the same. So from one man, my grandfather, having a simple labouring job over a century ago, hundreds of people grew up thinking work is normal.

Work has always been essential to human survival. In the societies my ancestors lived in, days were spent hunting, fishing and gathering food, building shelter and tools, and burning vegetation to make the land produce better food sources. If you didn’t work, you died.

The nature of work has changed. Modern economies rely on machines, computers, foreign trade and large-scale farming, manufacturing and production. People no longer hunt their own food or build their own shelters. They do other kinds of work to earn income they use to buy what they need from others.

All over the world, improved technology has radically changed the way humans live, leading to greater urbanisation. In Britain, there was a great exodus of people from rural areas to cities in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries seeking work in the factories and metalworks created by the Industrial Revolution. British towns grew fast and infrastructure and services lagged behind with poor sanitation, filthy streets and over-crowded housing. Horror stories of the workhouses and industrial workplaces are etched in the western imagination through tales of writers like Charles Dickens.

In truth, the rural lives people left behind were at least as, if not more, impoverished. Human life in pre-industrial society was extremely bleak; most people lived their short lives in a subsistence lifestyle in abject poverty. They also worked long hours in harsh conditions, mostly in seasonal agriculture. Britain experienced multiple famines and plague epidemics wiped out large proportions of the population.

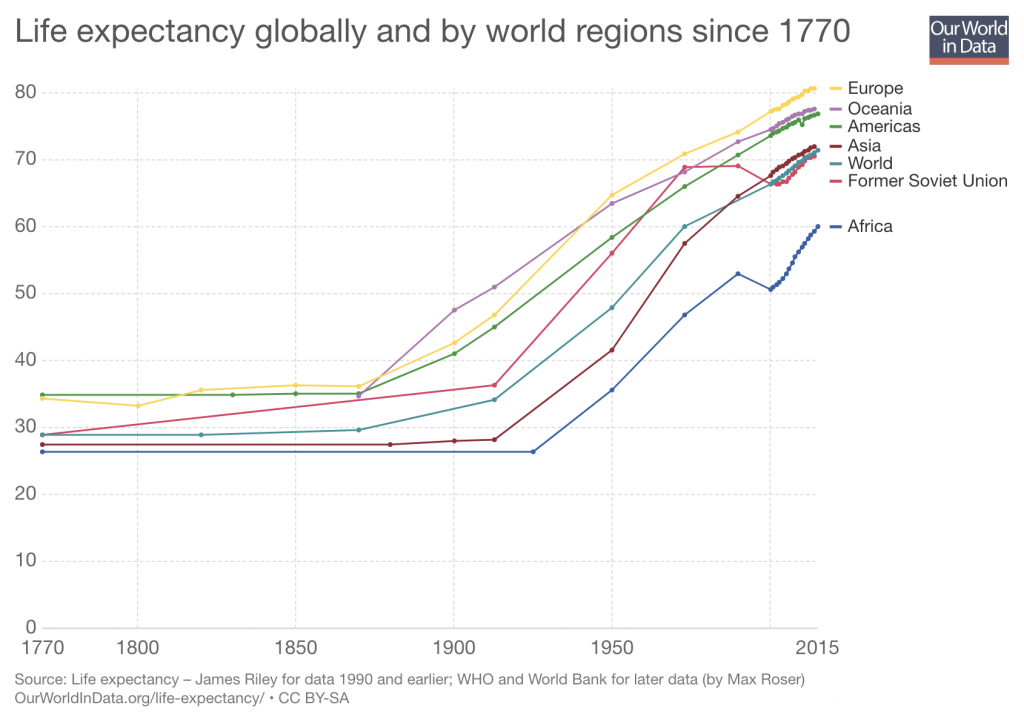

People flocked to new industrial workplaces for their survival and because they aspired for better lives. And human life did improve. Death rates dropped, life expectancy rose, wages rose over time, and food supplies and diets improved. Famine and plague came to an end. Average working hours shrunk and the cost of goods substantially decreased. Technological leaps since the early 1700s delivered extraordinary gains in human prosperity and quality of life.

Somewhere along the way during this amazing transformation, many of the intellectual classes stopped believing in work as essential to survival, beneficial, a source of pride, a virtue. They’ve come to characterise work as a negative.

I pinpoint the origins of this mindset to nineteenth-century political philosopher Karl Marx, who saw a working class exploited by business owners. To Marx, the source of exploitation wasn’t so much the conditions of nineteenth-century factories but the act of a business owner making a profit. Marx saw a world of finite resources which business owners and workers would increasingly battle over until the system eventually collapsed in on itself, leading to communist utopia. It didn’t. Technology increased resources, reduced need and made people better off. Actually, it was those states founded on Marxist ideology that experienced economic collapse. But, even as Marxist economies came and went, the idea of work as a form of exploitation has stuck and taken on a life of its own.

Increasingly we hear the idea there’s something wrong with wanting people to work. We hear welfare recipients shouldn’t be expected to work. We hear that requiring people to do work or activities in return for welfare is exploitation and wrong. That moving people from welfare to work is unfair because they’ll become part of the “working poor”. That some jobs, like seasonal fruit picking or even work someone is overqualified for, are just not good enough to expect people to go off welfare. That there aren’t enough jobs for unemployed people. That employers discriminate against older and disabled workers so there’s no point them trying.

When I first heard the expression “working poor” I had to ask for an explanation; even then I didn’t understand. People on welfare already live in poverty. So those who warn that welfare-to-work will create a working poor are really saying: being poor is undignified enough, it’s an added indignity to be poor and working. This is a terrible outlook. My family was part of the working poor my entire childhood. Working wasn’t an indignity. It was a source of pride. I’d choose to be part of the working poor over the welfare poor any day. Being in a job – any job – makes the next job opportunity – a permanent job, a higher paid job, a better job – much more likely.

Even outside of the welfare reform debate, we hear anti-work rhetoric. We hear it’s unfair if some people earn less than others, even if they’re less experienced or capable. The latest anti-work political idea is that governments should pay everyone a non-means tested Universal Basic Income with no obligation to work because it’s imagined most jobs will disappear.

The overarching message from the intellectual class is that work is exploitative, an indignity, a burden; that work enforces inequality, is scarce and even endangered. At least, that is, for the downtrodden, the poor, the unskilled, those on welfare, the young, the aged and the disabled; and, in the future, for most unskilled workers.

The mindset of work as something negative is allowing many families and communities to be destroyed.

* * *

The welfare safety net was one of the most significant public policy innovations of the twentieth-century western world.

In the tribal societies of my ancestors, people pooled their resources in large family groups. Those who could contribute had roles and responsibilities in caring for those who couldn’t, like the young and the aged. Aboriginal kinship systems acted as a natural welfare system. If someone you were responsible for in the kinship system needed or asked for your help, the law required you to help them. Most human societies began in a similar way, with small familial groups in close, subsistence living and mutual kinship obligations.

Modernisation and urbanisation saw these ancient structures change, often disappearing entirely. Congregated in large cities with people from many and disparate regions and origins, people couldn’t necessarily rely on kin to care for and protect them and were often reliant entirely on the churches and the charity of others to survive.

Most western countries today have expansive welfare systems. The unintended impact has been a permanent underclass of people; families dependent on welfare for generations suffering a myriad of socio-economic problems. Long-term welfare dependence is the new poverty in western economies.

In Australia, there are too many people who haven’t been working for far too long, stuck in a welfare trap that will swallow them up, and their children and grandchildren too, if the cycle isn’t broken. I speak about this a lot when it comes to Aboriginal people. But they’re just an infamous example of a problem that exists all across our country and many others.

The progressive left want increased welfare to address the poverty of welfare recipients. But even if you doubled welfare payments, recipients would still live in poverty. Poverty isn’t just about money. It’s about deprivation of basic needs like employment; lack of purpose and aspiration; lack of autonomy and independence. Welfare can never deliver these. The solution to welfare poverty isn’t higher welfare. The solution is a job.

Welfare campaigners rarely talk about moving people from welfare to work. They seem resigned to, even comfortable with, the idea of welfare as a long-term state. People, like myself, who say we need to move people from welfare to work are accused of being cruel (that’s the “work is exploitative, an indignity, a burden” mantra) or unrealistic (that’s the “work is scarce, even endangered” mantra). Their excuses for why people can’t be expected to move from welfare to work are wrong. All the hurdles have solutions. And it’s a lie that there aren’t enough jobs. Finding jobs for people is the easy part. The greatest barrier to moving from welfare to work is the gulf people find themselves in when they haven’t worked for a long time … or ever.

* * *

Andrew Forrest is one of Australia’s wealthiest men – a self-made billionaire who built an iron-ore mining company to rival the big, established players. He grew up on a cattle station in Western Australia’s remote Pilbara region. As a child he considered the Aboriginal people who lived and worked on the station as family and was disturbed to see how their, and so many other Aboriginal people’s, lives turned out when they were moved off the stations to live on welfare on the fringes of towns and cities from the early 1970s.

Forrest was determined to create employment opportunities for Aboriginal people. He created an employment model called Vocational Training and Employment Centres (VTECs) based on a simple principle that once a person had successfully completed training they would be guaranteed a job in his company.

He learned that for people who’d been dependent on welfare for a long time, skills training wasn’t enough. Many who came through the VTEC had multiple barriers to employment. Drug and alcohol addictions. No driver’s licence. Criminal records. No secure accommodation. Some couldn’t read or write. Some hadn’t worked before in their lives. The challenges didn’t end once the person started the job. Some workers went home after their first rostered period and didn’t return. Sometimes family members demanded their money. Whatever the hurdle the VTEC would help them overcome it.

What Forrest found was that if a person stayed in the job for twenty-six weeks, he had them for life. They’d never look back.

Forrest went on to encourage other organisations and governments to set up VTECs and the model has now been adopted by the Australian Government in its Indigenous employment strategy. In my book I have called on the government to set up VTECs for all unemployed people starting with a pilot program in the most welfare-dependent community in each state and territory of Australia.

* * *

Amanda is an Aboriginal woman from Western Australia. She was raised by a single mother and step-father and suffered severe domestic violence from a young age. She came to think the mark of someone’s love was them belting you. She had little schooling. At thirteen, she began sniffing paint, smoking cannabis and taking drugs. She spoke about how she lived her teenage years in a life of self-destruction, bad choices and despair, violent relationships and daily meth use.

Amanda heard about a VTEC opening up at Forrest’s Murrin Murrin nickel project. She decided to see if it could help her. It did. She was offered a job on the project. The VTEC trained her and helped her get job ready and overcome her considerable problems.

That was nearly twenty years ago. Today she’s still working. She married a man she met at Murrin Murrin. She hasn’t touched drugs since. She says her working life gave her responsibility, a sense of purpose and the ability to break away from the aspects of her childhood that had held her back.

Here was a teenager, her body addled with drugs and bearing the scars of a life of violence, with little education, no skills and no family support, walking up to a mining company and asking for a job. And the company gave her one. Giving someone a job is the greatest thing in the world you can do for another person.

Amanda now has three children. Because the company gave her a job, it changed the life trajectories of her children. Their lives weren’t marked by despair. They’ve grown up with parents who get up every day and go to work and provide for the family. They go to school every day. When they grow up, they’ll work too.

* * *

When I reflect on the modern attitudes to people who’ve fallen on hard times – the downtrodden, the poor, the unskilled, those on welfare, the young, the aged, the disabled – I feel that somewhere along the way, compassion has been replaced by pity.

Compassion is when you see someone in need and you care about them so much you want to see them back on their feet. Compassion is what you have for someone you respect, someone you regard as just as worthy as you, and just as capable of having a fulfilling and independent life. Compassion is giving someone a job or helping them start their own business. Compassion is insisting parents send their kids to school and take proper care of them. Compassion is what you show when you believe there’s always a way back.

Compassion is when your biggest priority is the person in need.

Pity is when you see someone in need and think their situation is so hopeless there’s no way back. Overcoming an addiction is hard. So is learning to read and write as an adult. So is working if you have a disability. You don’t want them to have to do anything hard or challenging, because you think that’s cruel. They’ve suffered so much, why should they have to try so hard to work, especially in a low paying, menial job?

Pity is what you have for someone you don’t really respect, someone you don’t regard as just as worthy or capable as you of having a fulfilling and independent life. Pity is giving people in need housing, medical care and schooling (but not making them use it) and a small amount of money so they don’t starve. Then, when that money starts to look a little thin, you demand the government gives them a bit more so they stay above the breadline and you don’t feel as guilty about their situation.

Pity is when you’ve written off the person in need and your biggest priority is yourself.

It’s not cruel to want people to work. And if you find someone a job and give them every assistance to start and retain it, it’s not cruel to insist that they do. That’s having respect for people by not writing them off, and believing they’re worthy and capable of having fulfilling and independent lives. That’s compassion.

The greatest thing in the world you can do for another human being is give them the opportunity to work. As hard as it is for someone to climb out of that gulf, it’s worth it. They never look back. Nor do the generations after them. Work is still essential to human survival – the survival of the human spirit. We need to reclaim work as a virtue.

This is an edited extract of Warren Mundine in Black + White: Race, Politics and Changing Australia, Pantera Press; (July 28, 2018) 498 pages.