The Munk Debate and the Perils of Tribalism

Tribalism isn’t a toy and academics who think they can regulate it up and down like a set of dials to determine who’s in which group

“[Y]ou’re a mean mad white man and the viciousness is evident.”

Michael Eric Dyson

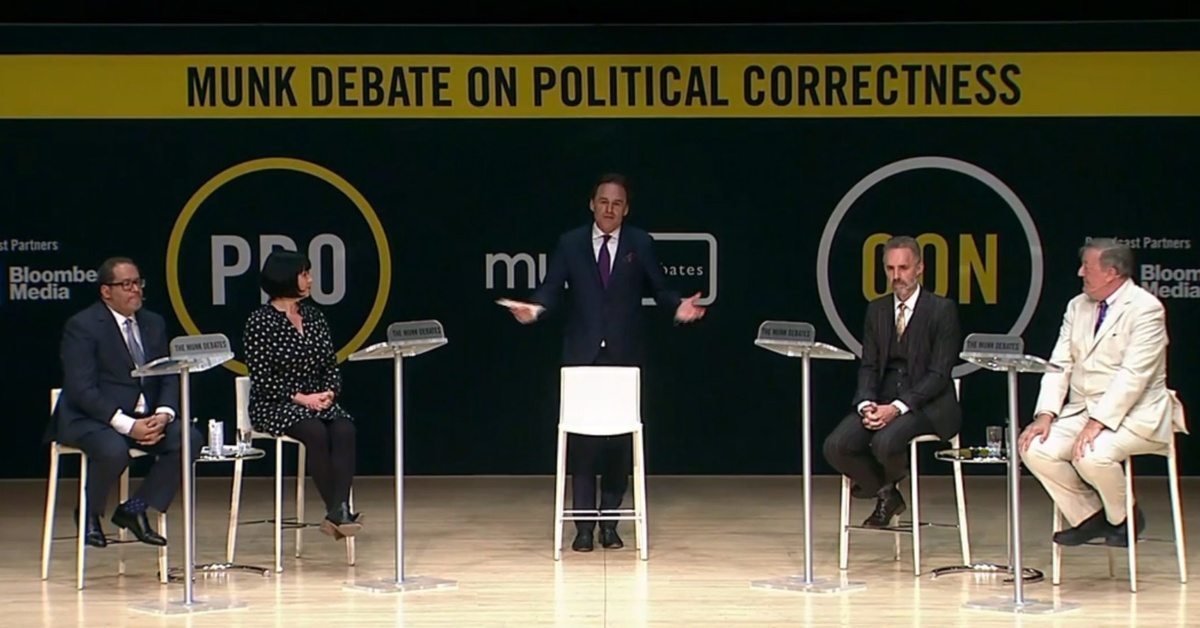

The Munk Debates is a semi-annual series of debates that take place in front of an audience of 3,000 people at the Roy Thomson Hall in Toronto. Two panellists argue in favour of a motion and two argue against it. Audience members vote on the motion before and after the debate, and the side that shifts the most votes in its favour is declared the winner.

The most recent instalment took place last Friday. It was titled: “Political Correctness—Be it resolved, what you call political correctness, I call progress…” The pro side consisted of sociologist Michael Eric Dyson and journalist Michelle Goldberg, while the con side consisted of comedian Stephen Fry and psychologist Jordan Peterson. All four are prominent authors and social critics. The debate was broadcast in both Canada and the United States, was streamed online through thousands of channels, and has received almost two million views on YouTube (across a few different channels) as I write this.

The debate was remarkable for one particular reason, which I’ll focus on in this piece. I’ve watched hundreds of academic debates over the past decade or so—on YouTube and elsewhere—starting with some of the early ‘New Atheist’ debates on religion and then moving on to politics, philosophy, and many other topics. Yet I’ve never seen one where a participant used derogatory racialised language as part of their debate strategy. Until this one.

Half an hour into the debate, Dyson made the following statement: “[I] ain’t seen nobody be a bigger snowflake than white men who complain.” An hour in, he said the following to Peterson: “Why the rage, bruh, you’re doing well, but you’re a mean mad white man.” When Peterson objected, Dyson responded with this: “The mean mad white comment was not predicated upon my historical excavation of your past, it’s based upon the evident vitriol with which you speak and the denial of a sense of equanimity among combatants in an argument. So I’m saying again, you’re a mean mad white man and the viciousness is evident.”

It’s indisputable, I think, that if Peterson had called Dyson a mean mad black man or had made derogative opinionated statements about black men, the moderator or other panellists would have objected. But here they said nothing. This is an obvious asymmetry: the panellists were debating difficult and important ideas in a competitive setting, yet Dyson was able to use racialised barbs to play to the crowd and get under Peterson’s skin.

Dyson is a sociology professor who by his own admission teaches French philosophers Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida, both difficult thinkers. He didn’t need special rules. So why did he get them anyway?

Dyson’s defence was essentially this: by racialising the conversation, he makes Peterson—and the audience—aware of the ways in which people of colour are forcibly collectivised by oppressive societal structures that are invisible to white people. He said: “When I added race to that, I was talking about the historically evinced inability to acknowledge others’ pains equally to the one that they’re presently enduring,” and earlier in the discussion said: “[I]dentity politics has been generated as a bête noire of the right and yet the right doesn’t understand the degree to which identity has been foisted upon black people and brown people and people of colour, from the very beginning on women and transpeople.”

This defence didn’t have much of an effect on Peterson, who during his opening statement had said: “Obviously, human beings have an individual element and a collective element, a group element let’s say, the question is what story should be paramount.” So while it’s possible Peterson underestimates certain forms of group identity, he never denied people were subject to them. His claim was that people on the left overemphasise them, and he appeared to think Dyson’s barbs were a further step in the wrong direction.

This tied into Peterson’s warnings about collectivism. He argued that the collectivist narrative is: “a strange pastiche of postmodernism and neo-Marxism, and its fundamental claim is that, no, you’re not essentially an individual, you’re essentially a member of a group,” and that: “the proper way to view the world is as a battleground between different groups of power.” In Peterson’s view, this is dangerous because not only does it produce conflict amongst the groups that initially adopt this mindset, but there’s also a danger of creating tribalism on the Right. Peterson and Fry both stressed this during the debate.

Psychologist Jonathan Haidt, who Peterson mentioned during the debate, has been a vocal proponent of the view that continuously subjecting students to identity group discourse produces a tribal mindset where students learn to see the world in terms of ingroups and outgroups. In other words, there’s a fine line between making people aware of their identities and sharpening their identities—or even producing new ones—through combative discourse. Peterson and Haidt have been arguing for some time that academia, especially the humanities, have gone too far towards the latter. Stoking group conflict is dangerous because you might not be able to control it once it has become inflamed.

In my opinion, while Dyson accused Peterson of being blind to his privilege and to various forms of enforced group identity and oppression, many on the political left also have blind spots, and I think this explains in part why Peterson is often dismissed so easily. Peterson’s work in personality research and clinical practice has arguably given him a better understanding of the broader population than most academics who tend to work and live in environments with predominantly like-minded people. (Although it should be noted that Dyson is a minister as well as an academic.)

For this reason, many academics might underestimate the extent to which most people don’t view the world through a lens of universalism and egalitarianism. For many people, tribalism isn’t a means to achieve equality, it’s at the core of their worldview. So when they feel their identity threatened, they’re going to fight back, regardless of whether academics think that they are privileged—they simply don’t see the world through that lens.

Tribalism isn’t a toy and academics who think they can regulate it up and down like a set of dials to determine who’s in which group and who can say what about whom are playing with fire. Theoretically, emphasising group identities and allowing marginalised groups to make derogatory remarks about other groups while strictly prohibiting the reverse might be an effective levelling technique that leads to more equality. In practice, though, there’s a real risk of it boiling over into serious conflict.

It seems to me that the audience felt the same way. The first time Dyson made a derogatory racialised remark about Peterson they laughed and clapped. The second time, a spattering of claps was quickly overshadowed by boos. When the votes came in after the debate, Peterson and Fry won handily.

There was a bright spot though. Dyson asked Peterson to come with him to a black Baptist church, and Peterson agreed.