Law

Portugal Poised to Write Gender Fluidity into Law

It’s difficult to say if it was really created to advance the rights of these people, or if it was simply cobbled together on some sort of whim.

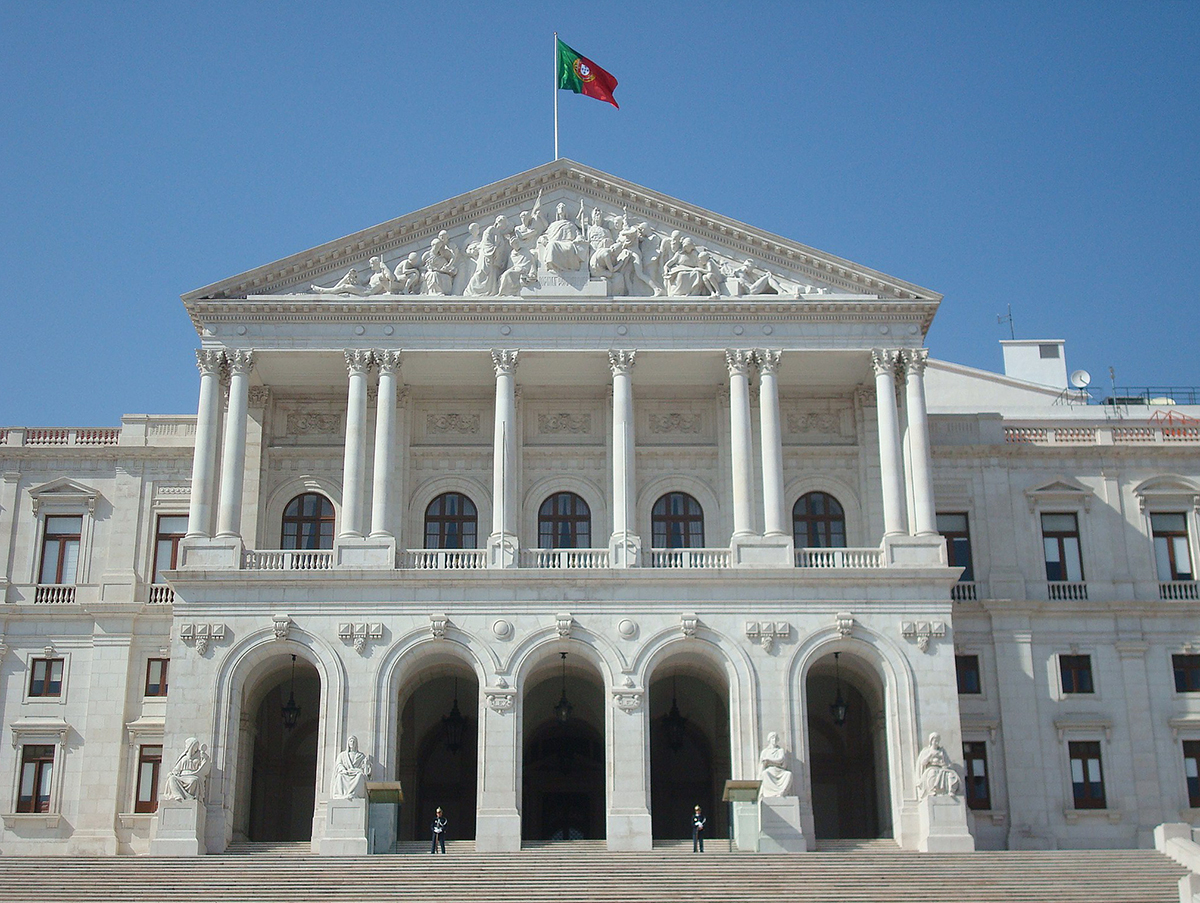

On 13 April 2018, the Portuguese parliament approved Bill 75/XIII, the ostensible aim of which is to protect the rights of transgender and intersex individuals. Looking at the details, however, it’s difficult to say if it was really created to advance the rights of these people, or if it was simply cobbled together on some sort of whim.

Portugal’s last parliamentary elections were held in September 2015, and a coalition of PSD (Social-Democrat Party) and CDS-PP (Party of the Social-Democratic Center) won the most votes, but failed to secure an overall majority. This allowed the country’s leftist parties (PS – Socialist Party; PCP – Portuguese Communist Party; PEV – Green Party; and BE – Leftist Block) to form a coalition government led by PS. The PS government has to make regular concessions to these parties because it needs their votes to pass new legislation.

In the case of this bill, that wasn’t really the case, since Bill 75/XIII was originally proposed by the government itself. However, later drafts included recommendations from their far-Left coalition partners in parliament, Bloco de Esquerda (Leftist Block) and the Portuguese Communist Party. Bloco de Esquerda successfully lobbied for the age at which a Portuguese citizen can change their sex and name in the civil registry to be reduced from 18 to 16; for anyone to able to do this without any kind of medical report (which was previously mandatory); and for intersex people to have the option of making those changes as soon as their gender identity manifests itself.

If you think that sounds like madness, try reading the Exposition of Motives set forth at the beginning of the bill. All scientifically minded people will know that the evidence for sexual dimorphism (I will not use the word gender to talk about psychological traits, since they don’t vary independently from physical sex) is overwhelming, and as close to a settled scientific truth as any we are likely to find. The opposing view, generally held by those in the social sciences who still use what Leda Cosmides and John Tooby have called the “Standard Social Science Model,” is that men and women’s psychological traits are nothing but a social construct. Unfortunately, it is the latter view that informs the theoretical foundations of the new bill, which then takes this unscientific nonsense a step further:

Effectively, the paradigm until now has been oriented toward a perspective of mental pathologizing of people who deviate from the sex or gender binary marker conceived as natural (masculine/feminine or man/woman), promoting social stigmatization, and this has now centered its attention on the social and legal situation of these people, as members of a society with rights equal to the other members and in the context of a universality of human rights, affirming gender self-determination of each person as a fundamental human right and an indispensable part of the right to the free development of personality.

In other words, this bill is no longer intended to address society’s alleged imposition of gender roles, it’s about upholding a belief that anyone can determine their own gender. This understanding of ‘gender’ has nothing to do with biology, but nor is it presented as a social construct. Instead, it forwards the idea that gender is nothing more than a psychological construct—the product of a ghost in the machine above all internal and external influences—and this will now be enshrined in Portuguese law.

I first heard about the bill last October, when I watched it being discussed in a televised debate. By this point, the bill’s opponents were already desperate. One of the debate participants was a psychiatrist, who repeatedly stressed the importance of properly diagnosing those who say they feel themselves to be the wrong sex. He itemised a number of conditions that could explain such a self-diagnosis, but which had nothing to do with gender dysphoria. He referred to patients who suffer from a variety of emotional or identity disorders, and even cited the case of a 60-year-old patient whose identity confusion vanished once a brain tumour was removed.

A paediatric surgeon asked the two participating members of parliament who were supporting the bill (one from the government, and the other from Bloco de Esquerda) what he ought to do if he had to operate on babies born with an intersex condition that required surgery in the first few days to save the child’s life. In such a situation, he explained, sex would need to be assigned at birth, something the bill explicitly disallows. He was simply reassured that the prohibition of sex assignment would not apply in such circumstances, even though no allowances for such exceptions were made in the text of the bill itself. He returned to his seat shaking in head in disbelief.

Throughout the months of January and February, several specialists were called to testify in hearings before the Parliamentary Sub-Commission for Equality. These experts included Dr. Pedro Freitas, a clinical sexologist, Dr. Íris Monteiro, a clinical psychologist, and three or four representatives from the National Council of Ethics for the Life Sciences, including Dr. Jorge Costa Santos. Every single one of them spoke against the bill, as it was then written.

Inter alia, they argued that a 16-year-old cannot—and should not—be allowed to take such consequential decisions at an age when he or she is struggling with identity; that a medical report is indispensable because a person cannot simply decide for themselves that they are transsexual; that a clerk at the civil registry would not be competent to evaluate the medical and psychiatric merits of each case; that the bill was intended to eliminate the diagnosis of ‘gender dysphoria’ while, at the same time, granting access to surgical and pharmacological treatments through the National Health Service (which is universal in Portugal); that gender identity is not self-determined, but rather something influenced by biological, psychological, and social factors; and that the civil registry policy must follow universally accepted criteria that the bill did not meet.

They also protested granting 16-year-olds the right to take legal action against parents who attempted to prevent their children from taking any of the steps permitted by the new legislation. This clause ended up being removed from the final document. Nonetheless, it was considered for a time.

Having followed the controversies in Ontario, Canada in 2017 regarding Bills C-16 and 89, I became involved in the discussion on my YouTube channel, and spoke to the psychologist Dr. Oren Amitay and the British LGBT campaigner James Caspian. After the bill passed through the Portuguese parliament, I also spoke to Jared Brown, the lawyer who accompanied Dr. Jordan Peterson at the hearing regarding Bill C-16. In addition to the objections already noted above, my guests and I discussed a number of other problems with the bill.

First, an early draft provided an extremely vague and ambiguous understanding of ‘indirect discrimination,’ which it defined as:

[Any] disposition, criterion or practice, apparently neutral, that puts people with a certain gender identity, gender expression, or sexual characteristics in a situation of disadvantage in comparison to other people, unless that disposition, criterion, or practice is objectively justifiable by a legitimate end and that the means to achieve it are adequate and necessary.

This article was excluded from the final document, but article 2, section 1 still reads:

Every person is free and equal in dignity and rights, being prohibited any discrimination, direct or indirect, in function of the exercise of the right to gender identity and expression and the exercise of the right to the protection of sexual characteristics.

Second, article 7 now reads:

The intersex person can require the procedure of changing [their] sex in the civil registry and the consequent alteration of name, from the moment their gender identity manifests itself.

As one of the members of the National Council of Ethics for the Life Sciences pointed out, gender identity starts manifesting itself as early as 3 years of age. Are we to understand that a 3-year-old intersex person can decide to go to the civil registry and change her sex and name?

Third, article 10 stipulates that:

The General Directorate of Health must define, within 270 days, a model of intervention by means of orientations and technical norms, to be implemented by the health professionals within the scope of the questions related to gender identity, gender expression, and the sexual characteristics of the people.

Since diagnoses of ‘gender dysphoria’ are to be discouraged from now on, this looks suspiciously like an appeal to the General Directorate of Health for the creation of new diagnostic guidelines favouring gender self-determination.

Fourth, article 11 stipulates the need for:

Adequate training directed at professors and all other professionals in the Education system within the scope of questions related to the problem of gender identity, gender expression, and the diversity of sexual characteristics of children and young people, bearing in mind their inclusion as a process of socio-educational integration.

Fifth, article 13 mandates financial compensation for “any discriminatory act, by means of action or omission.” Say hello to the legal precursor to compelled speech in the form of gender pronouns and so on.

Sixth, article 15 appears to afford considerable legal power to politically motivated activists:

It is recognized [that] the associations and non-governmental organizations whose statutory objective is the protection and promotion of the right to gender identity and expression, self-determination, and the right to the protection of the sexual characteristics of each person, [have] procedural legitimacy for the protection of the rights and collective interests and for the collective protection of the rights and legally protected individual interests of the associated people, as well as the protection of the values of the present Law.

I’m not entirely sure what this means exactly. In addition to being very badly written, the bill seems to be deliberately vague. But “procedural legitimacy” sounds to me like it grants the right to start legal actions in poorly defined instances of alleged discrimination.

James Caspian has tried to conduct a qualitative study of the increasing number of people who underwent sex reassignment surgery but later regretted it. During our discussion, he referred to Dr. Miroslav Djordjevic, a Serbian urologist who performs sex reassignment surgeries for both sexes, and who has also noticed this trend over the last few years. Serbia has recently become a hub for people who want to physically change their sex, and Dr. Djordjevic performs quite a lot of these surgeries.

The bill is unclear about how doctors and other clinicians in Portugal’s public healthcare system should treat patients who have changed their identity at the civil registry, and this confusion may make healthcare professionals vulnerable to charges of discrimination. Meanwhile, patients are to be granted access to all available surgical and pharmacological means to make their body match what they have in their heads, and at the taxpayer’s expense.

In a country that has the most expensive utility bills in Europe, high levels of corruption and corruption perception, taxpayers asked to bail out one bankrupt bank after another, and various other social, economic, and political problems produced by a feeble economic system, are anti-scientific nonsense bills like this one really among our most pressing priorities?