Art and Culture

Elham Manea: From Fundamentalism to Reform

“For a tiny minority, it is about the bloodlust of the battlefield,” she says. “However, for the majority, Islamists operate through nonviolence.

In February 2015, the gaze of the international media was transfixed by the case of three Syria-bound British schoolgirls. Amira Abase, Shamima Begum, and Kadiza Sultana were all pupils aged between 15 and 16 at the Bethnal Green Academy in east London. Without warning, they abandoned their GCSE studies and fled the safety of Britain for life in the nascent Islamic State.

The political and media class recoiled in shock and horror. Even though dozens of British males had already left to become militants in Syria and Iraq, the idea that apparently normal middle-class schoolgirls should be lured by a life of punishing austerity and violence struck a new nerve. The media reported on the story for weeks, and the girls’ tearful families made appeals before the cameras. By then, the trio had long slipped across the Turkish border into I.S. territory. They would not return.

From central Switzerland, an Arab academic followed the story closely and now ponders its larger significance. Elham Manea is an associate professor in the Political Science Institute at the University of Zurich. She maintains that she was always confident of the quick military defeat of I.S. but is convinced that the root of the problem is older and deeper than modern violent jihadist movements. For decades, the 52-year-old Muslim scholar has been researching Islamism. While it is the extravagant violence of groups like I.S. and Boko Haram that tend to generate the most media attention and lurid headlines, the real danger presented by Islamism comes from its ideological underpinnings that overwhelmingly manifest in nonviolent forms. Islamist women, she says, make this most clear. “For a tiny minority, it is about the bloodlust of the battlefield,” she says. “However, for the majority, Islamists operate through nonviolence. We ignore this at our own peril as they divide and radicalize our communities.”

For Manea, the study of Islamism is personal. I spoke with the professor in April when she embarked on a U.S. campus tour to promote her new part-autobiography, part-scholarly exposé, Der alltägliche Islamismus (Islamism Mainstreamed), published by Random House Germany. Manea told me about her own experience of radicalization and makes a surprising admission: “In another time, I could have easily been one of those girls.”

The Arab Cold War

In 1982, a 16-year-old Elham Manea returned to Sana’a, in what was then North Yemen, after living abroad in various countries for most of her life as the daughter of a diplomat. At the time, Yemen was divided into two states, both of which were embroiled in the Cold War. The Yemen Arab Republic, also called North Yemen, was a satellite state of United States ally Saudi Arabia run by a conservative tribal regime. To the east, the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen, also called South Yemen, was the only communist state in the Arab world and it enjoyed the political and economic support of the Soviet Union.

Fearful of communism and pan-Arab nationalism spreading further into the Middle East, Saudi Arabia used its oil wealth to fund and export pan-Islamism as a counter-ideology, and North Yemen became an Islamic bulwark against Marxism in the Gulf. By the late 1970s, imams at new mosques funded by Saudi Arabia were systematically spreading Salafism, an austere and hardline interpretation of Sunni Islam, based on an eighteenth century Najdi puritanical revivalist movement. President Ali Abdullah Salih made political concessions to conservative tribal leaders in exchange for their support, and indoctrination reached even the youngest members of society as the religious curriculum was retooled by Muslim Brotherhood members working in tandem with Saudi Salafi functionaries in the North Yemen education ministry. In 1982, Manea returned to a country vastly different from her childhood memories.

Like many teens navigating the difficult years of adolescence, Manea experienced an identity crisis compounded by being the new girl in school. Moving through several different countries during her young life had further isolated her from any particular national identity. In Yemen, people called her the “tall Egyptian” (she was born in Cairo and has Egyptian roots from her maternal side), while in Egypt she was referred to as “the Yemeni.” She remembers asking her grandmother over and over again: “Who am I?”

The Pious Sisters

In the transformed educational and political landscape, Muslim Brotherhood members and Salafi preachers were given free rein to proselytize on school grounds. At her new all-girls school, Manea remembers how some of her peers would sit in a circle during lunch breaks and listen to a charismatic female preacher. The group was dubbed the ‘Pious Sisters,’ and they eagerly encouraged her youthful curiosity.

Even though Manea already identified as a Muslim, her theological knowledge was limited and she did not practice. The preacher’s early instructions were simple and appealing: love others and do good unto your parents and neighbors. “I never felt like I was one, or whole, but then this group tells me, ‘You don’t have to look around. You don’t have two nationalities,’” Manea recalls. “Their message was beautiful. ‘In Islam, you are one. You are Muslim.’”

Over the subsequent weeks, the group’s message gradually began to change—and so did Manea. She started to wear a headscarf after hearing a lecture about hell, which, she now believed, was full of women hung by their hair as punishment for being seductresses. Manea also changed how she spoke to others, and began using Islamic greetings and expressions wherever possible. At first, these changes were relatively benign. But the more she obliged, the more was demanded of her. To practice ‘real Islam,’ she was told, she had to follow rituals and emulate the life of Muhammad, Islam’s Prophet, down to the tiniest of details recorded in the Sunnah (practices attributed to him). “There were lots and lots of rules. For a teenager looking for purpose, I found it.”

Eventually, the group’s meetings were moved off school grounds away from the eyes and ears of outsiders. But, by now, their message was increasingly proscriptive. Manea was no longer allowed to listen to secular music or partake in art—actions deemed haram, or forbidden—and most of the lessons were based on religious tracts distributed at meetings. These broached a wide array of subjects, like prayer or modesty, and gradually these became more political. This process of politicization became most evident to Manea when she was given a booklet on the life of Khalid al-Islambouli, the army officer behind the 1981 assassination of Egyptian president Anwar al-Sadat. The booklet declared Sadat to be an enemy of Muslims for making peace with the Jews. Islambouli, on the other hand, was a hero. Manea was also given tracts on jihad and martyrdom. The former was described as necessary to the promulgation of Islam, while the latter was held to be a supreme act of worship. The leader also manipulated her young charges by instilling in them a deep sense of victimhood; Kashmir and Afghanistan were offered as examples of how the Ummah—or global Muslim community—was under siege by the kuffar (disbelievers), Jews, and Crusaders.

Of all the disturbing writings she was given, Manea remembers one book in particular: Sayyid Qutb’s Milestones. The 1964 book by the Egyptian Islamist intellectual is regarded as the manual for modern jihadists. Qutb applied the term jahiliyyah—pre-Islamic ignorance—to Muslim-majority societies and declared it the duty of righteous Muslims to mobilize in a vanguard to create an Islamic state. Osama bin Laden was to become one of Qutb’s most notorious spiritual disciples.

Waking Up

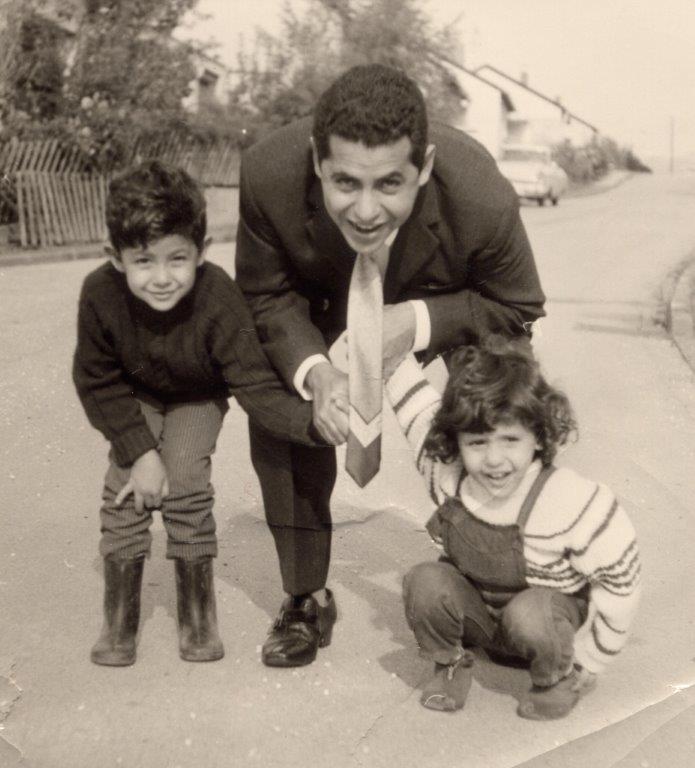

A 1969 photo of Elham (right) with her father and brother in West Germany. Photo courtesy of Elham Manea

Manea’s father was a freethinking agnostic. When he returned to North Yemen from an extended mission in Morocco, he was shocked to discover how much his daughter had changed in less than a year. Her curly brown locks were now hidden beneath a veil, and her body was always shrouded in a long garment. Concerned, he gently cautioned her about the group and their fundamentalist message. When she complained to the sisters about her father, their response was prompt and explicit: “He is an enemy of Islam.” The leader lectured her on how the early companions of Mohammed had such strong faith in God that they were willing to kill their own disbelieving families on the battlefield. By adhering to strict practice and belief, Manea was inheriting the legacy of the Salaf—the first three generations of Muslims—who practiced ‘real Islam.’ Breaking off worldly family ties, she was instructed, was a small sacrifice for the eternal rewards of the afterlife.

This response jolted her. Even though she had been inundated with radical lessons for months, these had been easier to process because they involved people she didn’t know and events in distant places. However, she had a deep and abiding bond with her father, a progressive who had always encouraged his daughter to pursue her dreams in the face of patriarchal Yemeni traditions. She could not see her loving parent as an enemy. “I spent so long trying to find an identity that in the end, those closest to me no longer recognized who I became.” Recounting this story, she pauses. It was at that moment, she says finally, that she began to think critically for the first time about the religious worldview she had embraced.

Later, in what would be the final group session she attended, Manea was presented with yet another lesson on the role of women in Islam. The leader recited a story from a hadith, a collection of actions and sayings attributed to Muhammad. According to the tradition, Muhammad scolds a woman for disobeying her husband when she visits her ailing father. Manea remembers experiencing a visceral reaction. “The preacher tells me Muhammad says the angels are cursing this woman and not the bastard who didn’t have mercy in his heart?” Her face flushes briefly. “I finally realized something was fundamentally wrong with this group. The God they preached about would not give me salvation.”

When she returned to her father, she told him, “I think you had a point.” Elham Manea never returned to the Pious Sisters.

Islamism Mainstreamed

The lessons she drew from that experience continue to inform Manea’s work 36 years on. Today, she is an associate professor of Middle East politics at the University of Zurich, a Muslim reformer, and a human rights activist. Although she didn’t realize it at the time, her experience with the Pious Sisters was actually a process of careful grooming and socialization undertaken by the Muslim Brotherhood. Each unit, called a family, was segregated by sex and had a leader who meticulously introduced the group to a body of political literature. Each student then moved up through a hierarchy, while continuously being tested, before finally taking an oath of allegiance to the transnational organization.

Elham Manea advocates for humanistic readings of the Qu’ran. Photo: Andy Ngo

When she settled in Europe in the early 2000s, Manea thought she had left Islamism behind her. She was startled to find her old Islamist booklets being distributed in prominent Islamic institutions and mosques. She now devotes her academic career to uncovering these networks, and her findings are grim. In her new book, she argues that we underestimate the extent to which nonviolent Islamists have gained influence among Muslim communities in the West. The systems and structures go beyond the Brotherhood to include South Asian and Turkish groups as well as social Islamist movements of various sects. “They’re well organized and are flush with money from donors, principally from Gulf states like Qatar, but also wealthy families from other countries,” she explains. “Leaving nonviolent Islamists without hindrance has led, in many contexts, to them closing certain communities from overall society.”

Nowhere can this be seen more clearly than in Molenbeek-Saint-Jean, a Brussels borough infamously dubbed the “Jihadi capital of Europe.” The suburb gained infamy for housing many of the I.S. terrorists who participated in the 2015 Paris attacks and the 2016 Brussels airport and metro bombings. In the course of writing her book, Manea visited the largely North African neighborhood and conducted interviews there. “What I saw and heard was haunting.” She did not see the moderate syncretic Islam she remembered from her time living in Morocco as a teenager. What she saw was Salafism. A high-ranking local police officer she interviewed alleged that youths celebrated on the streets of Molenbeek after the Brussels attacks.

When she began digging into the origins of Belgium’s oldest mosque, the Great Mosque of Brussels, she found it had been at the center of yet another strategic union between Saudi Salafis and the Muslim Brotherhood, which systematically built mosques, started madrasas (religious schools), created Islamic centers and bookstores, disseminated their literature, and gained political leverage by convincing politicians they were representing the Muslim community. “If you don’t understand their language, their literature, it’s easy to be fooled.”

Manea saw similar networks involving South Asian Islamist groups when she conducted research on British shari‘a councils for her 2016 book, Women and Shari‘a Law. “When you look at the extent Islamists have embedded themselves in Muslim communities, you will see that the consequences are not only violence, as we often hear,” she warns. “Women, children, and minorities within these communities are the first to suffer. We must think about the effects of Islamism on the most vulnerable as well as the wider effect on social cohesion.”

From her home in Bern, a medieval Swiss city wrapped by the Aare river, Elham Manea reads old reports on the British runaway girls that I sent her. Sharmeena Begum, one of their friends from the same school, had already made the trip to Syria a few months prior. At the time, Begum’s family told the media that their daughter was radicalized at meetings held by a “sister’s group” in the East London Mosque. She brought her three friends with her, they claim. The fate of all four girls remains unknown.

The story is eerily similar to Manea’s testimony, and she says we shouldn’t be surprised if the family’s claims are accurate. “These Islamist structures have been tested and developed for decades.” In our final interview, she issued a plea to Europe’s political leaders: “The group I was a part of never asked us to commit violence. I need to make that clear. But the ideas they indoctrinated us with pave the ground for violence. This is something we must wake up to.”

Featured pic courtesy of the author.

Andy Ngo is a graduate student in political science at Portland State University. Follow him on Twitter @MrAndyNgo