Education

The Return of the Canon Wars

By refighting the Canon Wars, there is hope that we can chart a more productive course than the one we have inherited.

Reed College recently announced that it would radically overhaul its core humanities course, Hum 110, in response to months of student protests. In doing so, Reed’s administration was, in effect, adopting the position of the course’s detractors; namely, that a focus on the Western classics “perpetuates white supremacy.” This decision—which did not go far enough for the students—is in keeping with an era of campus activism marked by a strident and narrow view of ‘inclusion.’ However, the demands of Reedies Against Racism, and their college’s swift capitulation, are far from novel. We are witnessing the return of the Canon Wars, reborn without the value of a credible opposition. And, while it is easy to be disheartened by this, the re-emergence of this academic conflict offers us an opportunity to address much of what ails the modern humanities and, by extension, the wider public discourse.

For a period in the 1980s and 1990s (imaginably before most of the Reedies Against Racism were born), the Canon Wars dominated the academy. In its most simplistic understanding, the battle pitted ‘traditionalists’ against ‘multiculturalists.’ The latter argued that the traditional humanities’ curriculum was a fossilized parade of dead white men and that it should be replaced with a more diverse body of authors. The traditionalists, to the contrary, held that the dismantling of the old syllabus would result in a crisis for the university and for the culture at large. In the words of Allan Bloom (whose influential polemic The Closing of the American Mind is usually credited with firing some of the first shots of this war), the revision of the canon along multiculturalist lines had “extinguished the real motive of education, the search for a good life.”

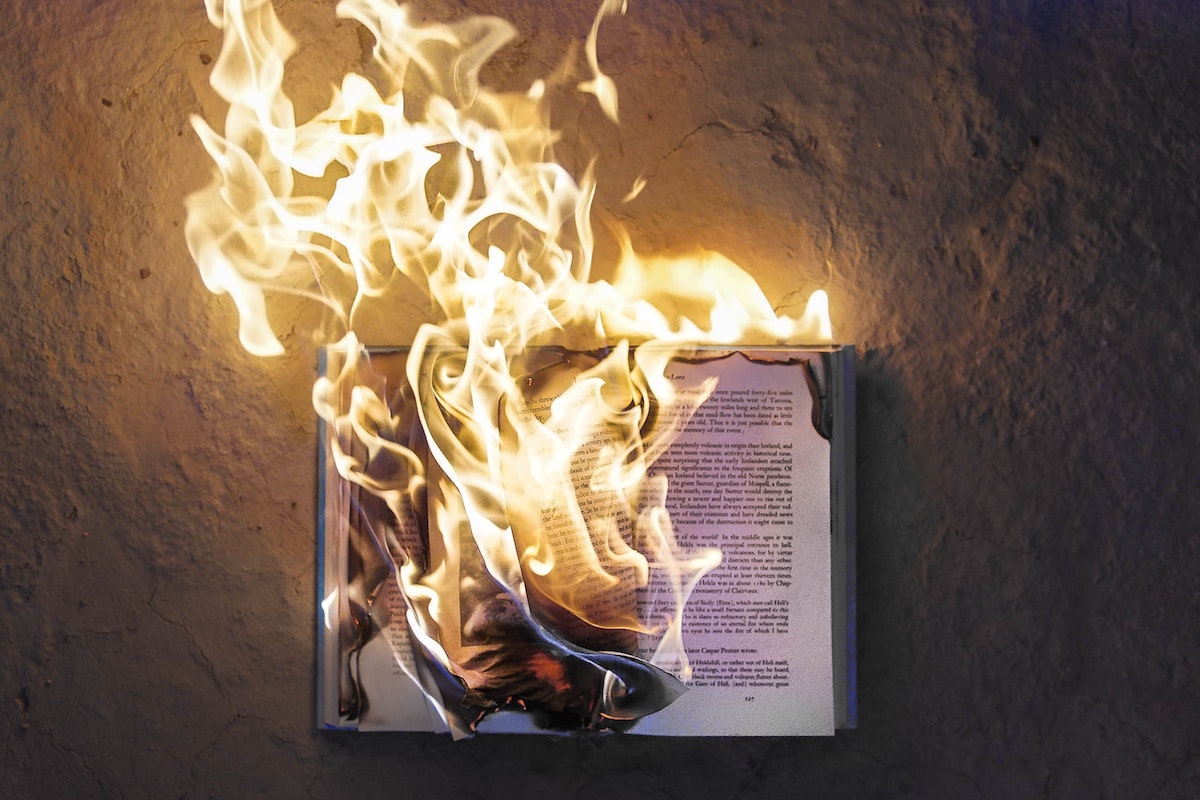

As it turns out, both sides were right. Not that the combatants could see that. Unfortunately, the real trouble with the Canon Wars, and the source of their myopic dogmatism, was not an earnest debate over which authors were worthy of a permanent place on the syllabus, but rather the ways in which each position became a proxy in the far more sinister and absurdly doctrinaire struggle for control of American culture. Nearly 30 years later, both camps have largely devolved into cartoonish parodies of themselves. The multiculturalists have given birth to the current crisis of free speech on campus, while the traditionalists have devolved into advocating reductionist, government-sponsored ‘Western Civilization’ curricula. Both positions seem like betrayals of the core values that once motivated their adherents. The multiculturalists have not made space for more voices, but fewer. Likewise, the traditionalists have seemingly surrendered the notion of rigorous pedagogy and fearless self-examination for the comfort of a legislatively-dictated education hardly worthy of the name. Neither position is sustainable and both present a grave risk to education and learning, particularly in the current climate.

That is why we should welcome the reignition of the Canon Wars. A good faith debate among scholars and others about the shape of the curriculum should never have been allowed to become subsumed in the easy soundbites of tribalistic politics. The current state of both our universities and our wider public discourse bear the mark of the Canon Wars’ failures, and the only way to repair what has been broken is to return to the fray. By refighting the Canon Wars, there is hope that we can chart a more productive course than the one we have inherited. A path that need not—and should not—end up returning us to either an uncritical acceptance of the traditional Western canon or a hodgepodge syllabus of mediocre talents collected only because we wish to appear open-minded.

To begin with, the goal of being ‘non-judgemental’ is, in fact, a strange one for those engaged in the teaching and study of the liberal arts to be pursuing. For most of civilization, the very purpose of a liberal education was to foster discernment and judgement—to encourage in the student an ability to distinguish the good from the bad, the beautiful from the ugly, and the wicked from the noble. The rise of moral and cultural relativism declared this goal to be an exercise in absurdity. If all things can ultimately be measured only against themselves, what good is the training of the mind to measure, weigh, and sort? Such absolutist relativism has been a failure. It has created a public discourse incapable of dialogue.

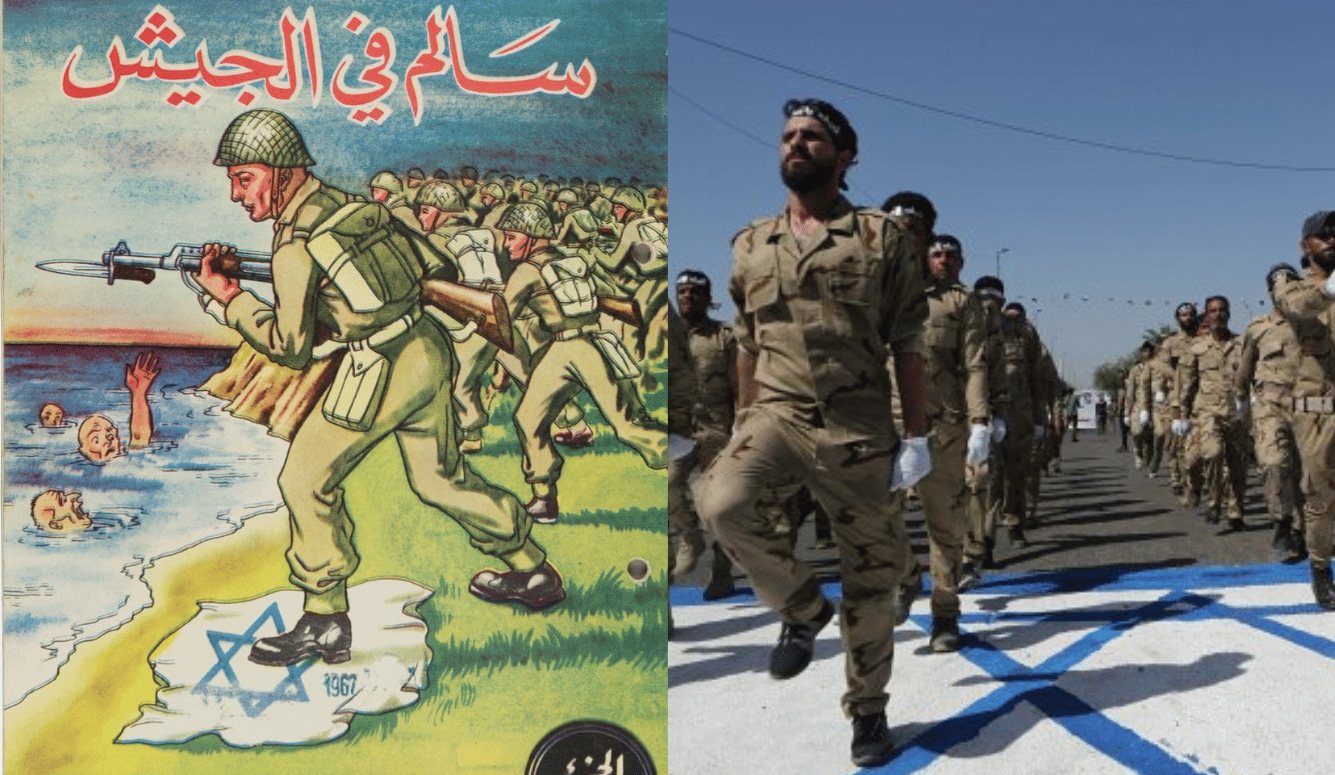

The influence of this relativism on the Left is quite clear. It has nurtured the disastrous notion that a person’s identity and tribal membership cards determine the ability of a reader to understand and respond to a text, undermining our shared humanity and our shared stake in the uniquely human property of reason. But the Right has not been immune, either. There too, logic and reason have been the chief victims, as the intellectual conservatism of yore has given way to an emotive traditionalist populism—identity politics marketed to a new chauvinistic audience.

The multiculturalist syllabus was shaped by a belief in relativism and its daughters. The multiculturalists hold that it is impossible to determine the very best works of literature humanity has produced, because there can be no objective standard of quality or merit. Thus, students should be guided to read texts from as diverse a field of authors as possible and to view texts as political artefacts and nothing else; they are to be understood as evidence of ‘identities,’ the prima facie reality of human life. This argument contains within it a hidden bigotry: the latent idea that authors from outside of the traditional Western Canon can only join the curriculum when we dispense with the standard of ‘good literature.’ That is the multiculturalists’ error—an error concealed from its proponents by an ideology that holds that one’s innate characteristics (race, sex, ethnicity, sexual orientation, etc) are more important and telling than what is said and done by the individual. This is not just artist over art, it is tribe over individuality.

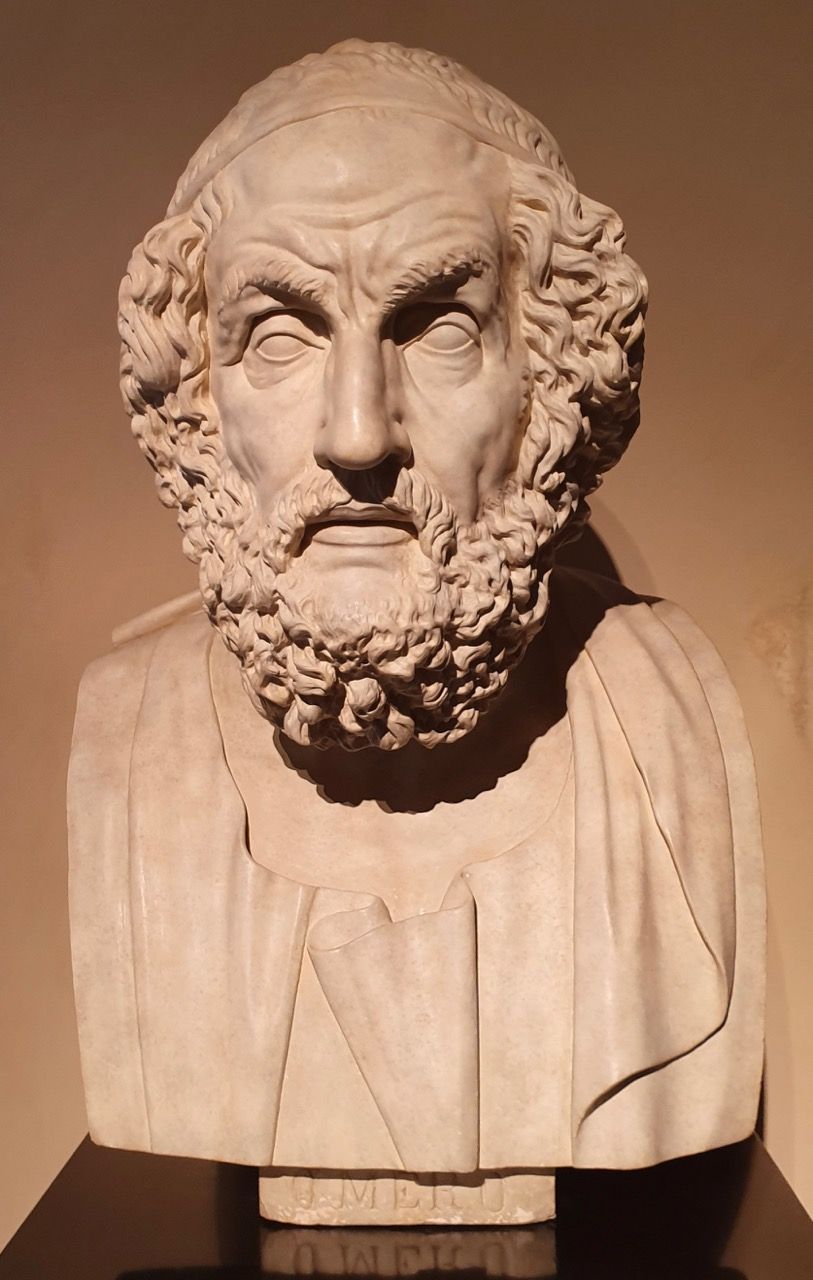

Conversely, the traditional canon, at its best, placed the individual at its center. The value of the traditional canon was, in large part, found in the philosophy that underpinned it: if one reads and studies the very best of what humanity has produced over the course of millennia, the mind will be better suited to the difficult but necessary task of fearless lifelong inquiry. The student of the ‘great books’ becomes the engaged citizen and the self-critical soul. This fundamental goal is the greatest asset of the traditionalist position. No doubt, there is much to love aesthetically in the traditional Western canon. The question, you may recall, of how to shape of the ideal soul (not the ideal city) is what ignites the debate at the center of Plato’s Republic.

The timeless storytelling of Homer, the complex characters of Shakespeare, the unparalleled wit of Voltaire are all of enduring value. But in many ways these texts are also, in this context, tools for the sculpting of the human spirit. The multiculturalists were wrong to abandon this fundamental goal 30 years ago, and they are wrong to abandon it now. Education must be more than a mere scavenger hunt for instances of oppression, cruelty, and hatred. It must ask how each of us can live better. The multicultural canon offers the voices of more individuals, but fewer opportunities for the student to look beyond the polis and into his own being.

With this objective in mind, it is possible to create a new canon that draws on the best of both arguments and offers students a more useful and comprehensive education. To this end, I would like to suggest the following parameters:

- The goal of a liberal arts education is to arm students with the tools necessary to lead a ‘good life.’ This good life includes acting as a responsible and engaged member of society.

- ‘Great books’ do, in fact, exist. That is to say, some works of literature are aesthetically superior to others. We can debate what these standards are and which texts meet those standards, but we must reject a relativist view of literary aesthetics that assigns to literature the mere status of sociological mirror.

- Great literature may come from any time and any place, but its value and ‘greatness’ must be divorced from the identity and characteristics of its creator. The qualities of a great book or magnificent poem are the same, irrespective of whether the author is male or female, black or white, gay or straight, writing in English or Yoruba. Every truly great text has something to offer every sincere student, regardless of the origin of either.

- Some texts, as a result of their influence, must be read as part of a comprehensive education. These texts might disproportionately come from cultures now regarded as ‘Western’ and this over-representation is, in many instances, a consequence of conquest and colonialism. However, it is dangerous to avoid an influential work merely because we cringe at the ways in which some of that influence was obtained. Into this category falls much of the literature of ancient Greece and Rome as well as the plays of William Shakespeare. Such texts not only benefit from cultural capital, but endure because of their unique beauty, timelessness, and universal resonance and appeal.

It is my conviction that, by using these standards, it is likely that we will arrive at a syllabus in which Homer co-exists with Toni Morrison, and Salman Rushdie co-exists with Milton. We must strive to create a curriculum that aims to educate above all else, that is not a hostage to the names and demographics of its canonical authors, and that does not become a pawn in a destructive political game.

The Canon Wars were not much fun the first time around, I am told. And it is certain that the fight will be even more unpleasant and bloody today. But this is a battle we cannot afford to leave unfought. At stake is what it means to have an educated soul and, for this reason, it is a battle we owe, not only to the academy, but to the polis at large.