Germaine Greer and the Emma Dilemma

Greer herself emphasized this point in drawing a distinction between “reform” feminism and “revolutionary” feminism.

Rescuing Jane Austen from Both Her Well-Meaning Admirers and Her Less Well-Meaning Political Critics

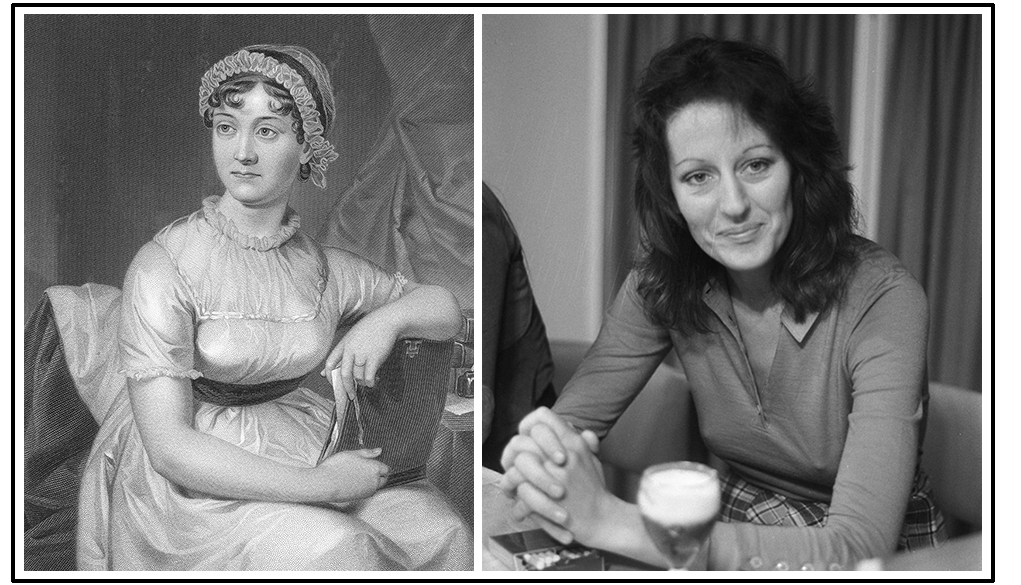

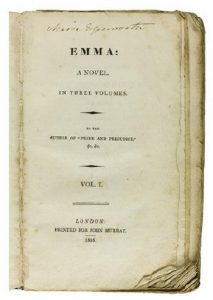

In the commentaries devoted to Jane Austen this year on the two-hundredth anniversary of her death, the cultural basis of her importance as a historical figure and of her great appeal as a novelist was largely overlooked, neglected, or misunderstood. The best way to approach this question is by comparing Austen’s Emma with Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch. Though at first glance these two books, one a work of fiction, the other of non-fiction, but each influential in its own way, would seem to have little in common, the story of Austen’s heroine in fact anticipates the actual experience of many modern women, including Ms. Greer.

To begin by clearing up one large misconception: Greer’s treatise is not only about women’s liberation.

Greer herself emphasized this point in drawing a distinction between “reform” feminism and “revolutionary” feminism. Reform feminists believed women could gain the same legal and political rights, equality of opportunity in education and career choices, and sexual freedom that men enjoyed by working within the existing democratic capitalist system. Revolutionary feminists rejected this traditional approach on the grounds that it did not get anywhere near the real problem: the capitalist social system itself. In their view, this system oppressed both women and men; and in order to liberate everyone, it was the task of women in particular to work to transform or abolish it.

Inspired by such counterculture godfathers as Norman O. Brown and Herbert Marcuse, Greer thus wed the revolutionary thinking of the 1960s to the particular issue of the condition of women. This enabled her to advance – in the name of women’s liberation – the same basic program for radical change that one finds in Charles Reich’s The Greening of America and Theodore Roszak’s The Making of a Counter Culture. All three redefined love as a public, free-floating, and promiscuous relationship between the “authentic” or “self-realizing” person and the “community” rather than a private, mutually caring, and monogamous relationship between two individuals. Liberating ourselves personally and socially in accordance with this revolutionary view, it was thought, would not just free us from the supposed oppression of practicing good manners, dating, courtship, marriage, and the nuclear family but would ultimately lead to a fundamental economic and political transformation of society as well.

Two decades after The Female Eunuch was first published, Greer appeared to acknowledge the failure of this revolutionary project even as she continued to insist on the necessity of pursuing it. In a preface to a new edition of her book in 1991, she lamented the fact that “The sudden death of communism in 1989-90 catapulted poor women the world over into consumer society, . . . You can now see the female Eunuch the world over; all the time we thought we were driving her out of our minds and hearts she was spreading herself wherever blue jeans and Coca-Cola may go.”

More to the point, Greer also in effect retracted her book’s central argument, namely, that women and men can and should dispense with monogamous love: “Twenty years ago it was important to stress the right to sexual expression . . . ; now it is even more important to stress . . . the right to safe sex, the right to chastity, the right to defer physical intimacy until there is irrefutable evidence of commitment, because of the appearance on the earth of AIDS.”

While it may be difficult, in light of the way AIDS is transmitted, to credit the reason Greer gave for her about-face, what she was offering here was basically an updated variation on the once-traditional advice to women about “saving yourself for marriage.” The value of such advice aside, this was a long way from promoting sexual promiscuity as a “revolutionary tactic” and declaring that “women must not marry.” The fact that Greer had now added this prefatory coda, so to speak, to her book clearly suggested that she had undergone an evolution away from celebrating the kind of personal irresponsibility that she expressly calls for in The Female Eunuch in favor of restoring a more serious attitude on the part of women and men toward sex and relationships.

While intellectual or ideological in nature, Greer’s change of heart recalls the moral evolution experienced by Jane Austen’s Emma, another strong-minded woman initially bent – though for personal not political reasons – on spinsterhood. As readers of the book will recall, Emma early on explains to her friend Harriet that, lacking neither money nor useful occupation nor social consequence, she has “none of the usual inducements of women to marry.” She then declares that “Were I to fall in love, indeed, it would be a different thing; but I never have been in love; it is not my way, or my nature; and I do not think I ever shall.”

In line with this self-assessment, Emma spends a fair amount of time and energy cultivating something of a goddess-like persona for herself on the basis of her preeminent social standing and the willfulness of her own spirit. Eventually, she realizes that acting in this manner has put her in the position, where personal relations are concerned, of being left out in the cold – “of being left in solitary grandeur,” as Austen puts it.

She also realizes that she has been doing “mischief,” to others and to herself, with her attempts at matchmaking (“With insufferable vanity had she believed herself in the secret of everybody’s feelings; with unpardonable arrogance proposed to arrange everybody’s destiny. She was proved to have been universally mistaken. . . .”). And by the end of the novel, she has come to think that it might not be such a bad thing to give up her goddess-like self-image for the affection, care, and comfort she can then give to and receive from Mr. Knightley.

There is much in this story that speaks to the sensibilities and situation of contemporary women: Emma’s independence, her determined character, and, most strikingly, her changing her mind about falling in love and getting married. It was Austen’s genius to imagine what has since become the most hip model of modern womanhood – the self-sufficient and self-satisfied spinster who later has second thoughts about being so.

It was also her genius – before Stendhal gave us Gina del Dongo and Theodore Dreiser, Sister Carrie and George Bernard Shaw, Eliza Doolittle; before Hollywood gave us Kitty Foyle, Now, Voyager, and The Farmer’s Daughter and Michelangelo Antonioni, Le amiche and Federico Fellini, Giulietta degli spiriti and Juzo Itami, Tampopo and Mina Shum, Double Happiness and Jean-Pierre Jeunet, Amelie; before the First Wave and the Second Wave; before, in fact, there were any waves to speak of at all – to grasp the fundamental predicament of the modern woman: namely, the necessity that she become the heroine of her own life. In other words, Jane Austen anticipated Oriana Fallaci.

For her existential insights, Austen seems, to say the least, underappreciated these days, her works often being treated, even by some of her admirers, as little more than delightful period pieces (suitable for cinematic adaptation or literary appropriation) or as quaint relics of a politically unenlightened past. In this connection, the Marxist-tinged critic Adam Kirsch wrote in the New York Times Book Review of the “foreignness” of Emma, asserting that “the most striking thing about” the novel is “the way it accepts its world, rather than rebelling against it.”

What do Jane Austen's novels have to tell us about love and life today? https://t.co/1EwEhHQO83 via @nytimesbooks

— The New York Times (@nytimes) December 28, 2015

Now, it is evident from Austen’s ongoing worldwide popularity that she isn’t even foreign to the foreigners, so to speak, let alone to the rest of us. And since she died the year before Karl Marx was born, Ms. Austen may perhaps be forgiven for not having realized that modern literature, as Mr. Kirsch put it, “is a literature of dissatisfaction” and for not having included anything about what he calls “current events” in her book.

But if it is true that Emma does not belong in the same class as, say, On the Road or Armies of the Night, it must also be said that Mr. Kirsch’s politicized approach has led him to falsify the book in fundamental ways. To take just one howling example: he writes that, “The richest people in the story, Emma and Mr. Knightley, are also the most perceptive and have the best judgment” – this about a heroine who not only repeatedly demonstrates both an extraordinary lack of perception and terrible judgment but at one point admits that the two most perceptive people of her acquaintance are Mr. Knightley and his brother.

Such failures of perception and judgment as Mr. Kirsch’s suggest that Emma’s account of hard-won humility continues to be an example for us all, worth studying even by dissatisfied literary critics (and their editors). More importantly, such failures illuminate the prevailing mode of considering Austen – as an author whose books exist, not for our pleasure and enlightenment, but merely for our entertainment – a mode that serves to disconnect her, her achievement, and her moral influence from the living present, to consign her, in effect, to the lending library of literary history.

What is overlooked by those who take such a patronizingly reductionist view of Austen is the fact that she speaks far more directly and profoundly to the actual experiences of modern women than a “revolutionary” feminist like Germaine Greer is able to do. And she does so because she investigates, with a sense of humor that matches her moral seriousness, situations of ordinary conflict in which personal quality and deep mutual regard triumph over social pretension and personal weakness, and women are called upon to make use of their freedom to choose whom to love or to marry or, like Austen herself, not to marry at all.

Depending on one’s circumstances, such choices may be no more self-evident than whether, as Austen concludes her novel Northanger Abbey, “the tendency of this work be altogether to recommend parental tyranny or reward filial disobedience.” But in addition to the usual complications of life, contemporary women face a problem that neither Austen nor Emma had to contend with: the ongoing tyranny of a set of countercultural ideas masquerading as “feminism.” Since at least the 1970s, our adherence to these ideas, however ineffective in overthrowing capitalism, has rendered monogamous love and marriage suspect. It has also promoted the transposition of the once merely personal and reversible choice of spinsterhood into a cultural or political imperative and a matter of endless ideological contention.

As a result, women who have wanted to marry have had to worry about the possibility of exposing themselves to public expressions of disillusion, censure, or ridicule on the part of those dedicated to keeping the countercultural faith. This prospect has perhaps been especially worrisome for women who have changed their minds or begun to think differently about whether falling in love is their way or their nature.

And not even professional feminists who have crossed this red line have been given a pass. Thus, the anti-marriage author and self-described “spinster by choice” Jaclyn Geller took the founder of Ms. magazine to task for following her own Emma-like trajectory and deciding to tie the knot: “Gloria Steinem has said, ‘Being a feminist is all about choice, and I have chosen marriage’ – and I think that is a horrifying misappropriation of the word ‘choice,’ I think, when you get to the point in relativism where even one of the most outspoken feminists is using this kind of ‘to each her own’ language, I think we’ve come to a very sad place indeed.”

Just how sad this to-each-her-own place can be was indicated by the writer Elizabeth Wurtzel, who likewise invoked the notion of choice as non-choice in making clear her Emma-ish wish to arrange everybody’s destiny: “Now obviously, freedom to choose is very much the point, but freedom to make nonfeminist choices – like being a housewife – is not okay at all. . . . We don’t have to respect everyone’s choices and we do have to say to certain women that they are behaving like idiots, that their choices are not good enough for a feminist world.”

In much less unpardonably arrogant and censorious language, but making the same sad point, the anti-traditional love author Laura Kipnis chided “the crop of twenty-something Ivy-educated women leading the so-called opt-out revolution, which is the new code for moms staying at home with the kids instead of ascending the career track”: “Somehow, as highly educated as these girls are, they don’t seem to have heard about the 50 percent divorce rate! Somehow they imagine that their husbands’ incomes – and loyalties – come with lifetime guarantees, thus no contingency plans for self-sufficiency will prove necessary! Let’s hope they’re right.”

One might have thought that simply being a woman is enough of a contingency plan for self-sufficiency in our modern Western democratic society – as many women both before and after the 1960s have proved by starting, stopping, or resuming their education or career while marrying, raising children, and even getting divorced. Be that as it may, the idea that life should come with lifetime guarantees of any kind (an idea that seems to belong more to Ms. Kipnis than to the women to whom she attributes it) was as anathema to the author of The Female Eunuch as it was foreign to Jane Austen, who died at the age of 41 after a lingering illness, not to mention Emma, who was too young when her mother died “to have more than an indistinct remembrance of her caresses. . . .”