Art

Why Postmodern Art is Vacant

Yet, modern art is still portrayed as being avant-garde, defying trends, and sticking it to the establishment.

Andy Warhol was and still is arguably the most recognisable face of modern art. His pieces sell for hundreds of millions, and to find one of his works at a garage sale or flea market would set you up for a very comfortable retirement. With his thick retro glasses and lustrous platinum wigs the man was the epitome of the avant-garde. The central function of his work and the work of his contemporaries was to jumble together high and low culture, to claim them as equal to each other, and to challenge our notion of what really was “worthwhile art.” Building on the work of the early conceptual artists from the turn of the last century, he tore asunder the old ideas of traditional aesthetic value, stating through his pieces that there can only be interpretation and that all works are of equivalent value.

However, when he died in February 1987 the world got a real look at Andy Warhol and what he really considered to be “worthwhile art.” Behind the doors of his neo-classical townhouse the rooms were not furnished by piles of Brillo boxes or indeed stacks of soup cans but objects of a rather different style. Classical busts sat on mahogany tables, portraits lined the walls, and on many surfaces sat fine antiques. Warhol had chosen to adorn his house with pieces that had stood the test of time, pieces that followed the old rules on aesthetic value, but most importantly pieces that would have been shunned in the art world he had created and dominated.

In his defence, like any shady salesman he knew not to use his own shoddy merchandise, he was at least honest with himself (if not with his public). Warhol was a salesman before he was an artist, as he hinted when he said, “Making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art.” This telling remark represents the mantra of the modern artist: willing to expose society’s greed, consumerism, and corruption so long as he receives generous compensation for doing so. The contradictions of Andy Warhol’s public and private tastes, along with the inherent contradictions present in modern art, expose it for what it really is – a fraudulent enterprise that does not stand up to close scrutiny; a con perpetrated by talentless hacks and the elitist snobs who give them both funds and oxygen.

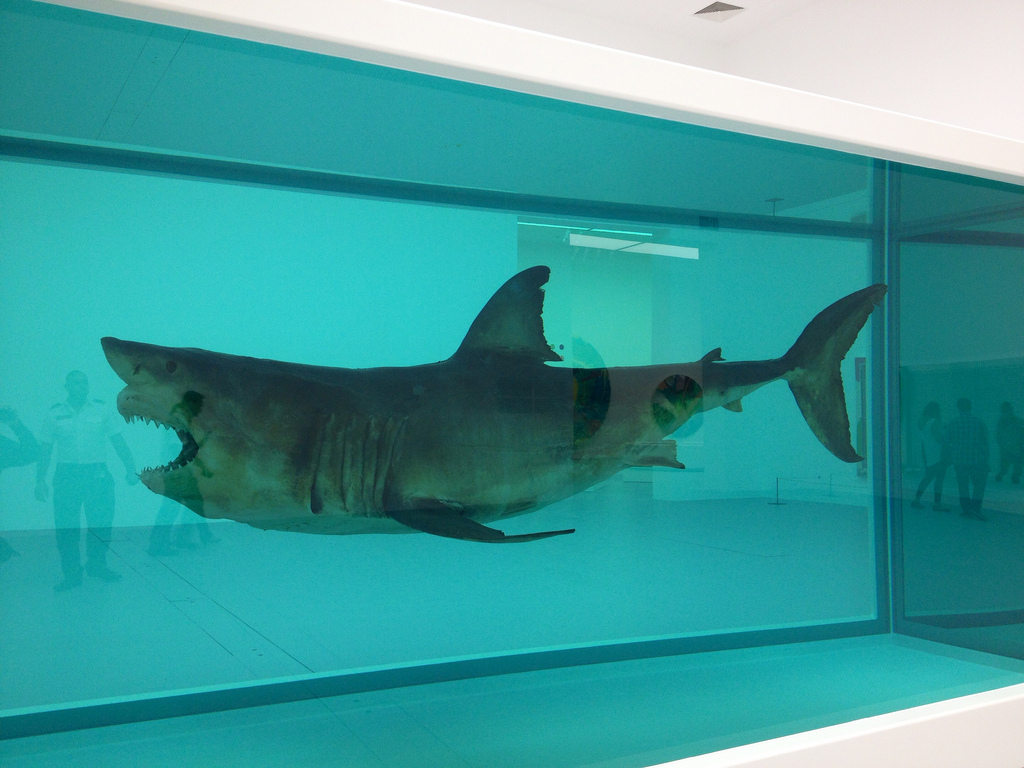

The fact is that from the time of Marcel Duchamp’s urinal to Damien Hirst’s pickled shark and beyond, the only people able to afford these modern art pieces have been the elite. An elite who, afraid they might fall behind the latest trend, nod their approval at a giant sculpture of a pair of buttocks (a Turner Prize-nominee), eager to show that they, like their elite friends but unlike the masses, “understand.”

Yet, modern art is still portrayed as being avant-garde, defying trends, and sticking it to the establishment. The people who buy these pieces are the very trend-setters it claims to rebel against. A quick look at who is actually purchasing these works shows celebrities like Madonna, Jay Z and Brad Pitt, tycoons like the Russian Billionaire Roman Abramovich, and advertising moguls like Charles Saatchi. Modern art is not anti-establishment: it is the establishment. On occasions when these works actually come into contact with real people, their judgement is unequivocal. In 2001, a Damien Hirst exhibit was thrown out by cleaners who mistook the beer bottles, coffee cups, and ashtrays for rubbish.

There are dozens more such instances. The cleaners of these galleries should be praised and not scolded, for they have displayed a firmer grasp of art than most critics, and appear to be the only ones willing to notice that the Emperor is naked.

The whole modern art scene has become stale; the ugliness, the obsession with the scatological, and the gratuitous levels of sexually explicit content are now tiresome clichés. While conceptual artists no doubt like to see themselves as being experimental, revolutionary, and unorthodox they have simply become boring. From painting with it (The Holy Virgin Mary by Chris Ofili) to tinning it (Artist’s Shit by Piero Manzoni), the uses of faeces has well and truly been exhausted by these charlatans. Pieces that were once seen as shocking no longer shock, the taboo has been broken, displaying a sexual explicit piece is now no more revolutionary than painting a bowl of fruit.

Not only are they dull and predictable, but the artistic skill of many of the big names in contemporary art is suspect. Behind the grandiose pieces and the attention grabbing works created purely for shock value lies a very important question: “Where is the skill and ability in all this?” No skill is required to place a rotting cows head in a glass cube with an insect-o-cutor (A Thousand Years by Damien Hirst). No ability is needed to set up a room with a light that switches on and off (Work No. 227: The Lights Going On and Off by Martin Creed, a work that won him the Turner Prize). It is most probably the case that the electrician who installed said lights and the abattoir worker who severed the cow’s head possess more skill and expertise than either Mr. Hirst or Mr. Creed.

In a 2015 interview with the BBC about his forthcoming exhibition involving marble carvings, Hirst was confronted by the interviewer with the charge that he does not make many of his pieces. Hirst replied that: “to carve one of these structures takes two years, and it’s like, I haven’t got time to learn to carve. But I know exactly what I want, and I want it to look perfect and I can make it perfect using these guys” (referring to a team of sculptors he had employed). He finished by stating, “It’s never been a problem for me in art and I don’t think it’s a problem…I mean it’s amazing that we’re having this conversation really.”

Michelangelo’s Pieta, carved by his own hands, took two years to create and was the result of thousands of hours of anatomical study. Mr. Hirst’s remark that he, “hasn’t got time to learn to carve” is symptomatic of what is wrong with modern art. His incredulity at having been asked such a question by a philistinic BBC interviewer is palpable. It is almost beneath him. Why should he – Damien Hirst, multi-millionaire darling of the art world! – waste his time doing something so trivial, so menial as actually crafting his creations?

A nonsense has dominated modern art theory (insomuch as there is a theory) that, after the horrors of two World Wars, a return to conveying the beautiful, the sublime, and the transcendent would be fruitless, unfeeling, and in some way would serve to whitewash history. As Theodore Adorno, one of the most prominent cultural critics of the Frankfurt school, declared, “Writing poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.”

This is piffle. It is true that nothing could match the scale of the Holocaust for organized brutality or the Somme for mindless loss of life. However, the Renaissance saw large scale wars across Italy and Europe between warring Kingdoms and city states, disease was widespread, and poverty was grinding. Yet in the midst of all this horror and death Italy and Europe underwent a cultural flourishing that yielded some of the greatest artistic masterpieces man has ever created. Late gothic art produced glorious carvings, panel paintings, frescos, sculptures and manuscripts in the years after the black death swept through Europe killing between 75-200 million people in a mere seven years. To somehow suggest that Botticelli’s “Birth of Venus” is any less captivating or magnificent post-1945 or post-1918 than it was pre-1939 or pre-1914 is fatuous.

To claim that the old aesthetic orthodoxies became obsolete after the horrors of the World Wars demonstrates a complete lack of historical knowledge and context. Such claims are a kind of virtue signalling. Those who made them wished to show how distressed they were with the state of affairs – that they felt so deeply they were no longer able to see beauty or form in the world. But it is precisely during or in the immediate aftermath of war that art and all it provides–beauty, consolation, affirmation, a feeling of transcendence–is most needed. Yet modern artists see fit only to contribute to the ugliness and desecration.

Marcel Duchamp famously pencilled facial hair on the Mona Lisa in the immediate aftermath of World War I. His Dada movement arose as a symptom of post WWI discontent with its obsession for readymade pieces that were literally any old bit of rubbish the artist found lying around. In 1921 Duchamp’s “created” a piece entitled Why Not Sneeze, Rose Sélavy? which consisted of 152 marble sugar cubes placed in a birdcage with a thermometer and a cuttlefish bone. He claimed he was producing these works in opposition to what he called “retinal art” art that was created merely to be pretty. He, on the other hand, was creating art, “in service to the mind.” How much of a “service” the above piece is to the mind remains an open question.

Paintings by Richard Jack and William Barnes Wollen convey the futility, the chaos and the brutality of WWI using traditional means. As for the Holocaust, one need only look at the paintings displayed at Yad Vashem in Israel, created by the inhabitants of the European ghettos and camp survivors. The works cross a broad range of styles yet most stay within the bounds of traditional aesthetic taste and form and aptly depict the misery and hopelessness of the camps and ghettos. Charlotte Buresova did not resort to gimmicks or rubbish-filled bird cages. Despite being imprisoned in the Terezin camp, she still drew pieces that showed the humanity of those around her. She and her fellow Holocaust surviving artists are a testament to the fact that, contrary to Adorno’s assertion, beauty and consolation can be achieved long after the cannons have fallen silent and despite the horrors witnessed and perpetrated.

It is foolish to say that this breakdown in realism and art in general can be put down to the traumatic events of the first half of the 20th century. Something much more nuanced appears to have been at work. The Dadaists and those who thought like them went through and came out of the wars convinced that the old techniques and traditions were now redundant and to be thrown on the bonfire. They rejected the old ideas convinced that the world was forever in flux and that it was time to start anew in an era were this flux was to be embraced. Objectivity was no more. Everything and anything could now be considered art, and everything was as good as anything else.

Intriguingly, there is another movement that broadly mirrors the development of Dadaism: that of the Postmodernists, more specifically the ‘Frankfurt School.’ Like the Dadaists, their genesis was in the interwar years but also like the Dadaists their influence really only started to be felt in the post-War years. They too came out of the first half of the 20th century traumatised. They were appalled by the rise of fascism, but also crestfallen at the failure of Marxist-Leninism to deliver utopia. Having conducted a postmortem on Marxism, they formed their own new ideology, still heavily influenced by Marx but with a new emphasis on the cultural rather than the economic. Like the Dadaists, they also felt the old traditions should be thrown on the rubbish heap of history – faith, family, and the nation had to be destroyed. And, like the Dadaists, they were convinced the subjective was king and objective truth was dead. Affirmation and construction were to be abandoned for desecration and destruction.

After the war, Adorno threw his weight behind many aspects of modern art in his posthumously published book Aesthetic Theory. Both ideologies complemented each other and marked the beginning of the postmodern age we are living through today. Both sought to wipe away the underpinnings of Western thought and tradition but without any coherent idea of what ought to replace them. Just as it is nearly impossible to see any stylistic trends common to the work of the Dadaists, it is difficult to find any workable, functional alternatives to Western reason and culture in the writings of the Postmodernists. Each thinker seems to have their own vague idea about what should come next. A responsible iconoclast does not attack traditions and institutions without offering some sort of coherent alternative.

The institution of art is merely another one of the institutions the Postmodernists have marched through, tearing apart everything in their path. Having succeeded in destroying the underpinnings of art, declaring everything to be art–and moreover good art–while emptying the word ‘beautiful’ of meaning, modern artists are now stranded on an open prairie. With no fences to restrain them or give them direction, they wander aimlessly, often getting lost in the process. The very term “art” now means nothing. For if everything is “art” then “art” is everything, therefore why define it as “art” at all? Why have galleries or exhibitions?

The only way to restore meaning to the word “art” is to set some clear objective parameters, and to vanquish aesthetic relativism. This does not mean these parameters cannot be tested and breached; the early Impressionists rebelled against the old standards and produced wonderful art. But it does mean that, like the early Impressionists, any advancements that are made must be tempered by imposing new parameters and still retaining a level of acknowledgement and respect for the older traditions.

Exactly what these parameters should be is a topic for another essay, but it is vital that the need for such rules is acknowledged, along with an acknowledgement that things have gone too far and that “art” is now a term used far too loosely. Unless this is done, the very idea of “art” will be lost to an all encompassing definition that includes everything and excludes nothing. This is precisely the outcome that Adorno and his cohorts desired.