Education

Bald Men Fighting Over a Comb: Arguments About the Classical Tradition

The Culture Wars and Beyond is an exemplary study: thorough, balanced, judicious, elegantly written, and all the better for its notably even tone and scrupulous sense of fairness.

Part I: A review of Classics, The Culture Wars and Beyond by Eric Adler. University of Michigan Press (1st November 2016).

Classics, the study of Greek and Latin literature, involves philosophical and historical texts as well as literary works. Classicists may also be interested in the systematic study of language and expression, and (to a lesser extent) art history and archaeology. In fact, Classics encompasses virtually every aspect of ancient Greek and Roman culture between the first Olympic Games in 776 BC and the fall of the Roman Empire in AD 476. Still, classicists have traditionally focussed their attention on Athens between 508 and 323 BC, and Rome between the mid-first century BC and the late second century AD: most of the important classical texts, monuments and works of art were created in those places during those periods.

Classics requires a long training: there are two ancient languages which take years to master, and a large body of impressive but often difficult literature in Greek and Latin that cannot be avoided. If you have not read most of this literature, or have taken shortcuts with it (speed-reading individual works in translation to save time or effort, for example) then you will have little worthwhile to say about any of it.

In the early twentieth century, Latin was offered by a quarter of British schools, and compulsory for pupils who wished to go on to university. But by the 1960s even Oxford had dropped Latin as an entry requirement. Between 1965 and 1995 the number of schoolchildren studying Latin and Greek shrank by four fifths, and has since continued to decline. In June 2015, there were 1,285 A-level candidates in Latin throughout the United Kingdom, no more. That same year, 253 students sat for A-levels in classical Greek.

Professional classicists, desperate to make the subject ‘relevant’, have spent a generation or more experimenting with Classical Civilisation courses in schools, and Classical Studies programs in universities, as ways of teaching Latin and Greek literature in translation to students who are likely never to learn Latin or Greek. After a generation of these attempts, Classics remains as marginal, eccentric and unpopular as ever.

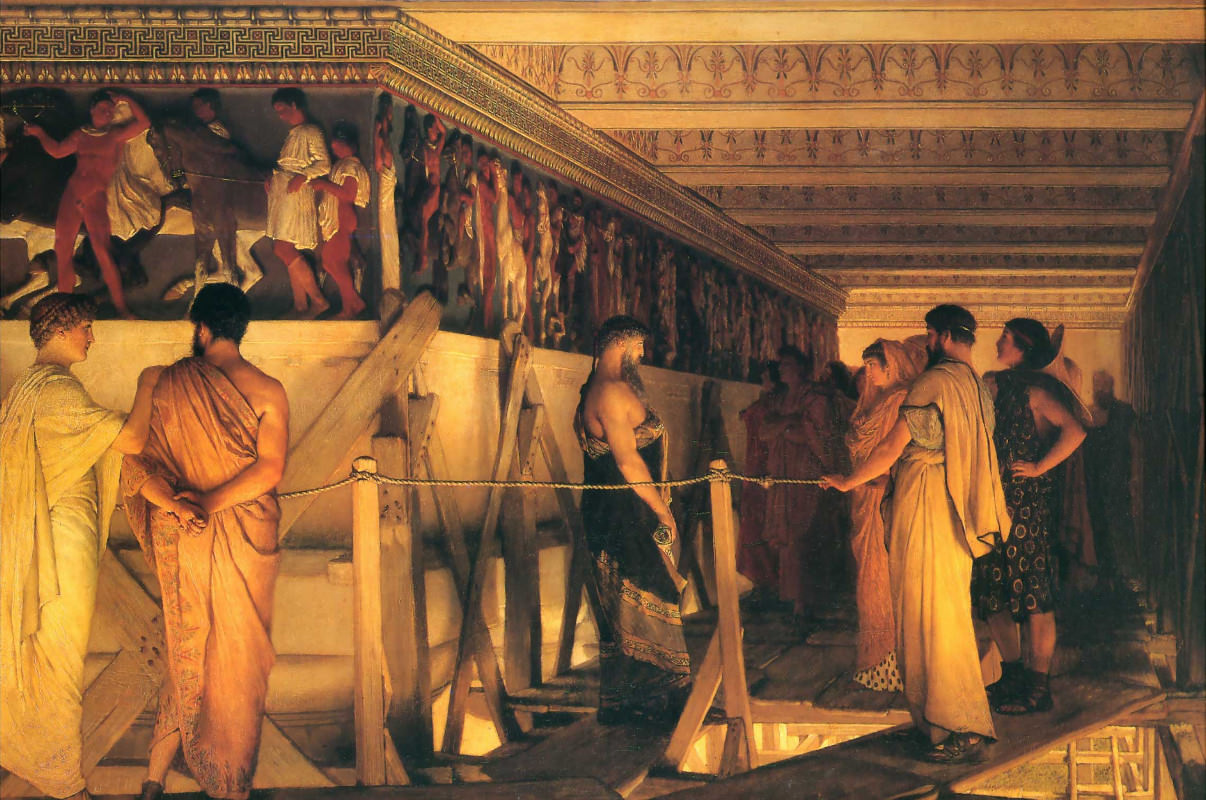

For all their discipline’s loss of status, classicists retain some sense of how important Latin and Greek once were, and have helped create a new field of study to remind others of the fact. Classical Reception is the study of the ‘afterlife’ of Graeco-Roman culture in later periods. This subject can be rich and fascinating, particularly where it involves (for example) the relationship between ancient mythology and the art of the Italian Renaissance, or poets like Milton, Pope or Shelley and their complex responses to classical literature in their greatest works. Alas, topics like these demand levels of competence and learning that modern academics rarely have. Also, any scholarship of genuine value and worth takes time and thought to produce. But the modern academic world is in a rush.

For decades American universities have put scholars under great pressure to publish their research, at first to advance their careers, now for a hope of even having one. The ‘publish or perish’ culture has spread worldwide, and only become more intense and oppressive with the expansion of universities, and the growth of elaborate bureaucratic structures for university administration. Academics must keep up a steady pace of writing and publishing articles every year, and books every few years, regardless of whether the results are of use or interest to anyone. Scholarship has become an absurd form of journalism, which nobody wants to write or read. Yet it is now more crucial for scholars than teaching, at least in professional terms.

For a disciplined scholar, this ‘publish or perish’ requirement is an annoyance rather than an insurmountable obstacle. Genuine contributions to knowledge can still be made, provided a scholar can find time to research, think and write, and enjoys access to a decent university library. The real problems, certainly for British academics, are ‘impact’ and ideology.

There are valid reasons for demanding that scholarly publications have some ‘impact’ on academics who wish to engage with their ideas or make use of their discoveries. But the idea that this can be measured statistically is laughable, certainly in a shrinking, cabalistic field like Classics, which grows ever more subdivided by increasing specialisation even as the number of classicists drops. Yet administrators demand that scholars at least pretend concern about how frequently their work is cited by other scholars, even if this is more a measure of how often they can afford to travel to conferences, give unpaid talks, or otherwise meet academics who will mention their research in a footnote, or refer to them in some other way which bureaucrats can quantify.

This has helped create a curious dilution: for classicists a cunning way to grant measurable ‘impact’ to their work is to produce ‘interdisciplinary’ research.

English Literature still attracts students in large numbers, and maintains its influence in the world outside schools and universities. It has replaced Classics as the central discipline in the humanities: no academic field (outside of STEM subjects and medicine) enjoys so much power, authority or funding. Thus classicists have an incentive to avoid working on their own subject and concentrate instead on (say) how a given English writer or literary circle made use of classical materials, or ‘the classical heritage’ more broadly (whatever this means). This is currently the most common form of interdisciplinary research for classicists: studying English.

One problem with Classical Reception of this sort is that English Literature, whilst much easier to study than Latin or Greek, is still an exacting discipline. It maintains its own specialised sets of technical skills and analytical approaches, as well as its own canons of ‘classics’ which must be read (although scholars, particularly in America, have been arguing for a long time about what should be included in these ‘canons’, or whether such things should even exist).

The most important canonical English writers, from Geoffrey Chaucer to TS Eliot, have sometimes been dauntingly erudite, and even a non-scholar like Shakespeare could read Latin more easily than most current undergraduates in Classics (and, really, most current academic classicists). To understand their responses to ancient materials and culture demands deep, intense thought, which ends up being almost as time-consuming as traditional research into Greek and Latin.

Latterly however, Classical Reception studies have favoured cases where artists, writers and other ‘culture-makers’ have little or no direct experience of Latin, Greek or other elements of Greco-Roman culture. ‘Translations’ of ancient poetry by poets who cannot understand the ancient languages will frequently be scrutinised; even more popular (by academic standards) are modern stage versions of Greek tragedies where nobody involved with the production can read a word of classical Greek. Classical Reception has also strayed more and more from high culture to focus on the relationship between ancient literature in translation and comic books, films, video games and other ephemera of popular or mass culture.

There may be an element of self-indulgence in devoting one’s research time to one’s preferred leisure reading, the TV shows one watches to relax, or one’s favourite theatre productions. But the ‘Postmodern’ Classical Reception scholar will argue that this is no different from what ‘literature snobs’ do when they try to find ways to research the ‘highbrow’ authors whom they read in their spare time.

For Postmodern scholars, taste is purely a ‘social construct’: there is no intrinsic value or quality in a ‘classic’, a ‘masterpiece’, or a literary or artistic ‘canon’. ‘Greatness’ is simply a term applied to given historical figures, and ‘cultural products’ are part of a status game or power grab by a group that wishes to be perceived as an élite. If this is all true, then studies of ‘trashy’, obscure or forgotten ‘cultural products’ are no less valid or useful than examinations of supposedly ‘great’, ‘important’ or otherwise ‘canonical’ art and literature. Perhaps they are even more important, if popularity and mass appeal are thought to matter more than traditional, common-sense notions of quality and value.

Of course, such a position undermines every possible reason for the existence of Classics. Why bother suffering through years of Latin and Greek when classical culture isn’t necessarily superior to fun video games? Most classicists working in universities today don’t have a defensible answer to this question. If they do, they tend to keep quiet about it. Such an answer would contradict the orthodoxies currently dominant among academics; to question any of this may be to commit professional suicide.

Eric Adler’s superb new book Classics, The Culture Wars and Beyond (University of Michigan Press) helps explain how Classics finds itself in the current state. The focus is on three major controversies that erupted among American classicists between 1987 and 1998; these disputes centred round class issues, Radical feminism and perceived racism. All three involved attacks on Classics by Radical-Leftist authoritarians; in all three Classics emerged as the loser.

Georg Luck (1926-2013) was a rigorously old-fashioned Latin scholar who spent over twenty years teaching at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. In 1987 he reluctantly became editor of the American Journal of Philology, the second-oldest Classics journal in America. This appointment was meant to be temporary: Professor Luck had already edited this journal from 1972 to 1981, and knew how stressful the position would be. Also, his predecessor had left behind a mess, including immense backlogs of unanswered correspondence and articles which had been accepted for publication but not yet published. Professor Luck accepted the editorship on the condition that he be allowed to leave the post in September 1989.

One of the new editor’s first tasks was to assemble a new editorial board for the journal. He assembled a group of like-minded colleagues, all of whom were highly distinguished, and shared his views on Classics as an exacting technical discipline. The traditional term for their approach to Greek and Latin language and literature is ‘philology’.

Classical philology is the technical study of classical literature and the ancient languages, from a variety of linguistical, historical and critical perspectives. The aim is to establish correct, error-free texts, and gain the fullest possible understanding of what is written in them. For a philologist, grammar, syntax and rhetoric are neither dry nor boring: they are essential tools for analysing how Julius Caesar’s memoirs are so vivid and gripping, and why the letters and speeches of Caesar’s enemy Cicero remain so powerfully persuasive, two thousand years after the author’s death, even though they were written in a dead language.

Philological techniques of studying Latin and Greek were invented and developed over the course of the Renaissance; though the golden age of classical philology was in the German universities in the nineteenth century, where it was refined and perfected into an art. The finest modern scholars aspire to attain something like the mastery of the great German philologists, because nobody else has come closer to helping us understand the charm, wisdom, beauty and sheer magic of classical literature.

Professor Luck was replacing an editor who had let the American Journal of Philology drift from its original purpose. It was time to reassert the journal’s guiding principles, and enforce consistent, coherent editorial standards. In the autumn 1987 issue, Professor Luck and his editorial board published a brief statement, “AJP Today”, affirming the journal’s commitment to traditional philology, which was fast disappearing from classical scholarship, certainly in America. “AJP Today” was a mild, sober, cautious document, meant above all to help young scholars see how they might contribute to the journal. Nobody could possibly find it offensive, unless one were looking for a fight.

The Women’s Classical Caucus was set up in 1972 as an affiliate of the American Philological Association, which remains the largest professional organisation for classicists in America. During the first decade and a half of its existence the WCC had enjoyed a few successes as a feminist pressure group; though the group was hardly well-known, even among classicists. Its main aims involved promoting feminist-inspired research into classical subjects, and combating perceived ‘sexism’ among classicists. “AJP Today” said nothing about feminism, and could in nowise be perceived as ‘sexist’; even so the WCC demanded a special session at the December 1987 conference of the American Philological Association to discuss the statement.

The special session was attended by around a hundred participants. Nothing much happened during the session or afterwards. Yet many classicists were alarmed by the vehemence of this protest against Professor Luck, whose main crime (other than not mentioning radical feminism in “AJP Today”) was to include on his editorial board only one woman, Professor Mary Lefkowitz, who was neither a feminist nor particularly radical, and so was not on friendly terms with the WCC’s leadership.

When Professor Luck stood down as planned from the American Journal of Philology, most readers presumed that he had really been fired. This impression was strengthened by his successor’s decision to include several prominent WCC activists on the editorial board, and to drop Professor Lefkowitz.

The “AJP Today” controversy turned into a public relations coup for the WCC. By writing triumphant articles about it after the fact, WCC activists were able to strengthen the rumour that they were really behind Professor Luck’s resignation, and even his retirement from Johns Hopkins; after all, the American Journal of Philology decisively changed direction after his departure, and ceased to be a genuine philological journal. In 1990 the Transactions of the American Philological Association, the oldest Classics periodical in the United States, followed suit and announced a new policy of ‘openness’ to all types of classical research—except for the approaches championed by Professor Luck.

The progressive victory over ‘conservative’ philology has been complete: in 1992 the WCC formally incorporated, and has grown from a small band of activists into one of the most influential professional organisations in American Classics. Meanwhile, the American Philological Association has since changed its name to ‘The Society for Classical Studies’. The old name no longer reflected what the society’s members do.

The hero of Classics, The Culture Wars and Beyond is surely Professor Lefkowitz, who found herself at odds, not merely with the WCC, but also with Martin Bernal (1937-2013), a scholar who had trained at Cambridge as a Sinologist, and taught for most of his career at Cornell University.

Bernal’s father had won the Stalin Peace Prize in 1953; though he himself was an enthusiastic Maoist, a position that became increasingly uncomfortable during the 1970s, particularly for a specialist in Chinese politics. During a sabbatical year, Bernal decided to teach himself about linguistics, and gradually managed to convince himself that ancient Greek civilisation was derivative of Egyptian and Phoenician civilisations, and that the fact had been covered up by generations of ‘racist’ European scholars. The resulting study, Black Athena, was published in three volumes in 1987, 1991 and 2006.

Bernal’s original manuscript was universally rejected by academic editors and university presses, so he passed it along to his friend Robert Young, who ran an independent press called Free Association Books. This freed him from the usual constraints of academic peer review.

The book’s title, Black Athena was meant to provoke scholars and also sell books. Bernal’s connections also helped: on 13th March 1987 the first volume of Black Athena was favourably reviewed in the Guardian by the ‘New Left’ intellectual historian Perry Anderson, who had known him since the 1960s. This review alone ensured decent sales, and also attracted the attention of an editor at Rutgers University Press, which ended up publishing all three volumes of Black Athena without its undergoing any of the conventional scrutiny required for an academic book.

Classicists initially dismissed Black Athena, as Bernal expected, and perhaps hoped. After all, it portrayed them, their discipline and their entire profession in such an unflattering light that that he could easily deflect their criticism as mere jealousy: the first volume sold well enough among ‘general readers’. Sales turned out to be so good that scholars could not afford to ignore Bernal’s more provocative contentions for very long. In January 1989 he was invited to the American Philological Association’s conference, where a classicist from Howard University organised a high-profile ‘Presidential Panel’ on Black Athena.

Many classicists claimed to welcome Bernal’s views on systemic racism among nineteenth-century philologists. Some of these long-dead scholars were indeed bigots by any standard. The first volume of Black Athena won an American Book Award in 1990. The second volume, published in 1991, was rather worse received. Now that Bernal had finished trashing philologists and philology he had to practise some of his own; he turned out not to be very good at it. His paranoia and vindictiveness were also beginning to show: the beginning of volume two was taken up with responses to bad reviews of volume one. Bernal attributed hostility to Black Athena to political, intellectual, temperamental or methodological conservatism, which to him were all one and the same thing. He was keen to contrast these against his own independence, originality and sense of adventure.

Even enthusiasts of Black Athena Part One turned against Part Two. Bernal was as incompetent to deal with archaeological evidence as he was with technical linguistics; the project revealed itself to be the work of a crank, and scholarly reviewers rightly made this clear. Luckily for Bernal, Black Athena found him an unexpected ally in the Afrocentrist Movement. Many of its leaders were autodidacts, and they all shared Bernal’s hatred for academic traditionalism. Some were also viciously anti-Semitic, as Professor Lefkowitz soon found out.

Professor Lefkowitz’s review of the second volume, “Not Out of Africa”, was published in The New Republic on 10th February 1992. She tried to grant Bernal due credit for his work, and the energetic relish with which he carried out his research; but she found little to praise in Black Athena, and censured Bernal for helping “provide an apparently respectable underpinning for Afrocentric fantasies”. He replied angrily; she counter-replied; he counter-counter-replied; a feud began. Bernal was not merely aggressive in his responses; he also stood serenely by when his Afrocentrist allies abused her as a “hook-nosed, lox-eating, bagel-eating … [something] … [something] … so-called Jew.”

Professor Lefkowitz eventually edited a collection of scholarly essays, Black Athena Revisited (University of North Carolina Press 1996), and also wrote a book, Not Out of Africa: How Afrocentrism Became an Excuse to Teach Myth as History (Basic Books 1997). She had to get her side of the story out: Bernal’s pursuit of this feud was becoming obsessive. He was quick to accuse his adversary of being “conservative” and “right-wing”, which was not true (and anyway not a crime). But the accusation stuck, which meant that ‘liberal’ academics were reluctant to support Professor Lefkowitz in public. Nobody thought to mention that Bernal was an avowed Maoist.

One of Bernal’s Afrocentrist allies sued Professor Lefkowitz for libel in December 1993, claiming that she had maliciously labelled him an anti-Semite. Around that time he also self-published a book entitled The Jewish Onslaught: Dispatches from the Wellesley Battlefront. It took five and a half years for the courts to dismiss this spurious lawsuit.

Demonised for years by Afrocentrists, Professor Lefkowitz bore the abuse gracefully. An example will be found on YouTube, in videos of her March 1996 debate in New York City against Bernal and an Afrocentrist lecturer. This is less a debate than a kangaroo court. Yet it is worth watching in full, as a demonstration of how learning, reason, common sense and good manners can be overwhelmed by the tactics of an unscrupulous, nihilistic demagogue like Martin Bernal. Classicists should be ashamed to have taken his side against Professor Lefkowitz. But in America at least, more of them seem currently to agree with him than her, in terms of politics, intellectual approaches, and respect for basic techniques of scholarship.

If Professor Lefkowitz is the hero of Classics, The Culture Wars and Beyond, then the villain is Professor Judith Hallett of the University of Maryland. As an activist member of the WCC, she was not only involved in manufacturing the “AJP Today” ‘controversy’, she also had a prominent role in the controversies that erupted around the book Who Killed Homer?

Who Killed Homer? The Demise of Classical Education and the Recovery of Greek Wisdom was co-written by Victor Davis Hanson and John Heath, who had met as PhD students at Stanford. Hanson had been brought up on a raisin farm near Fresno, California; Heath came from an unremarkable suburb of Los Angeles. They were both dedicated, passionate teachers; neither quite fit in among their more snobbish peers and superiors in Classics. They lacked the savoir faire to understand, for example, that it was bad form for a classicist to be seen to deviate from colleagues’ opinions.

In January 1993, Heath submitted an opinion piece to Classical World on the state of Classics in American universities. He saw that the real divide in the discipline was between a very small number of self-promoting, posturing ‘grandees’ at the top of the profession, and the majority of classicists, who couldn’t afford to waste time debating political or theoretical issues, because they were too busy trying to carry out their basic duties of teaching, research, administration and ‘professional service’. The editor of Classical World sent the piece to an associate editor to revise it for publication. This associate editor was Professor Hallett.

Professor Hallett took issue with his criticism of her Radical-feminist allies in Classics and made him cut several ‘questionable’ passages. Heath thought Professor Hallett was simply subjecting him to “editorial therapy and sensitivity training”. She decided to send the article to two fellow-activists from the WCC, who returned comments to the editor of Classical World accusing Heath of homophobia, misogyny and “conservative bias”. The editor was now scared to publish it.

It took almost three years to edit the article; Heath was forced to rewrite it five times. But the editor wanted nothing to do with it unless Professor Hallett and her allies were appeased. After a great deal of pleading and negotiation, the article was eventually published in the September-October 1995 issue of Classical World. Professor Hallett insisted on publishing it alongside critical responses from her colleagues; though Heath was allowed a final reply to his critics. Yet he did not have the last word: the editor of Classical World showed Heath’s critics his rebuttal, and allowed each of them to alter their original remarks in light of his reactions.

Heath was understandably frustrated and exasperated after his experience with Professor Hallett and Classical World. He and Hanson decided to write a book together about what was wrong with Classics in American universities. They agreed on three core premisses:

- the “core values of classical Greece are unique, unchanging and non-multicultural”, and are responsible “for the duration and dynamism of Western culture”;

- “the demise of classical learning is both real and quantifiable”;

- the “present generation of classicists” deserves most of the blame for the death of classical education in America, through their narrow-minded careerism no less than their fashionably ‘anti-Western’ politics.

They wanted teachers, lecturers and professors to try to embody the virtues inherited from Greek civilisation. These were based on:

- “seeing the world in more absolute terms”;

- “understanding the bleak, tragic nature of human existence”;

- “seeking harmony between word and deed”;

- “having no illusions about the role culture plays in human history”.

Gradually these virtues developed into a collection of principles fundamental for Western civilisation. Heath and Hanson referred to these collectively as ‘Greek wisdom’, which included:

- independence of science and research from religious and political power;

- civilian control of the military;

- support for consensual, constitutional government;

- the separation of religion from political authority, as well as its subordination to it;

- trust, faith and confidence in ‘the average citizen’, rather than the rich or poor;

- immunity of private property and free economic activity from “government coercion and interference”;

- the right of citizens to dissent from and criticise government, religion and the military.

Heath and Hanson thought that ancient Greek civilisation could teach modern Americans disdain for political correctness, for moral relativism and for the social sciences, among other contemporary evils. But none of this was being taught in the universities. Classicists, they thought, had become self-absorbed, self-indulgent, and more concerned with their own professional privileges than educating their students.

To Heath and Hanson, the most destructive development in Classics was the advent of Postmodernism. Scholars who broadcast their anti-élitist, anti-establishment, anti-authoritarian principles were really trying to become an élite, authoritarian establishment themselves. They were indeed as ‘subversive’ as they claimed to be, if not more so: they were not merely subverting a bunch of stuffy, privileged, powerful old white men: they were undermining and poisoning Greek wisdom itself.

Who Killed Homer? was published in March 1998, and received favourable reviews in newspapers and the popular press. Advance publicity in the New York Times helped attract further attention; Hanson would soon transform from an obscure historian at an unknown provincial university to a nationally-famous intellectual. Meanwhile, the volume’s reception among classicists was almost universally hostile: reviews of Who Killed Homer? in academic journals were intemperately, angrily polemical, with few exceptions. Numerous distinguished scholars unwittingly demonstrated that Heath and Hanson were right about the state of the profession, and its toxic, suppressive political correctness.

Who Killed Homer? was impolite and often ad hominem in criticising the excesses of individual classicists. Heath’s and Hanson’s observations were on the whole just; but the authors were needlessly insulting in some places. This was not the book’s only flaw. It was unevenly structured, unbalanced in its tone, and weakened by rambling exposition. Heath and Hanson were not always coherent, and sometimes let a good rant get the better of them. Also, their grasp of intellectual history was uncertain in places. Still, Who Killed Homer? was a positive contribution to a broader debate about the humanities. Or it should have been.

When attacked, the ‘tenured radicals’ fought back with the most slanderous insult they knew, and branded Heath and Hanson ‘conservatives’. Ironically, the firestorms that erupted around Who Killed Homer? may have been what finally pushed Hanson to the right (Heath has, despite his reputation, consistently remained a liberal). It is difficult to think of a single Classics book since Who Killed Homer? that has so flagrantly opposed professional orthodoxies. Classicists have learnt how to recruit, train and hire only those scholars who will keep in line with received opinion; and junior academics know to stay quiet if they disagree.

The single most shameful reaction to Who Killed Homer? came from the woman who helped inspire the book in the first place, Professor Hallett. In May 1999 she claimed to have alerted the FBI to the possibility that Heath or Hanson could be the famous terrorist ‘the Unabomber’. She said that both men had a lot in common with the Unabomber’s manifesto, in content as well as style. But Professor Hallett’s story did not hang together chronologically: it was mere slander. The resulting scandal proved even more of an embarrassment. Or it should have.

Despite overwhelming evidence, Professor Hallett has never admitted to lying about telephoning the FBI; Heath concludes that she invented the story as revenge for a cutting review which Hanson wrote of one of her books in 1998. But she was never ostracised, or even subjected to very much criticism, as a result of her actions. Whereas if Heath and Hanson had claimed to expose a Radical-feminist colleague to the FBI as a potential terrorist, they would have been swiftly and brutally punished by their colleagues.

Classics, The Culture Wars and Beyond suffers from several notable weaknesses. Eric Adler’s grasp of intellectual history can be shaky, particularly in his account of how classical philology and education evolved together during the Renaissance. His book only really comes to life when discussing events from the nineteen-eighties onwards. Adler focusses too narrowly on Classics in universities, and neglects the role of the Catholic church especially in maintaining and promoting the study of Latin and Greek in America. In general he relies far too heavily (if not uncritically) on the outlines of intellectual history developed by Heath and Hanson. On the other hand, some of his criticisms of Who Killed Homer? are especially fatuous. He sometimes tries too hard to offend nobody, and in doing so fails to assert a clear position.

All these flaws are minor. Classics, The Culture Wars and Beyond is an exemplary study: thorough, balanced, judicious, elegantly written, and all the better for its notably even tone and scrupulous sense of fairness. Eric Adler has done a great service to his discipline with this book, which deserves to be read by every Classics student and aspiring classicist. Of course, this market is vanishingly small: Adler’s statistics on the current state of Classics in American universities is particularly depressing, as are his undeniable conclusions that disputes about Latin, Greek and related subjects played no measurable role in the ‘culture wars’ of the last twenty-five years: little controversies within Classics were already too insignificant for non-classicists to take notice of.