Art and Culture

Cultural Appropriation Isn't Real

Being imaginative is more important for a writer than being from the “right” ethnic background or having the “right” experience.

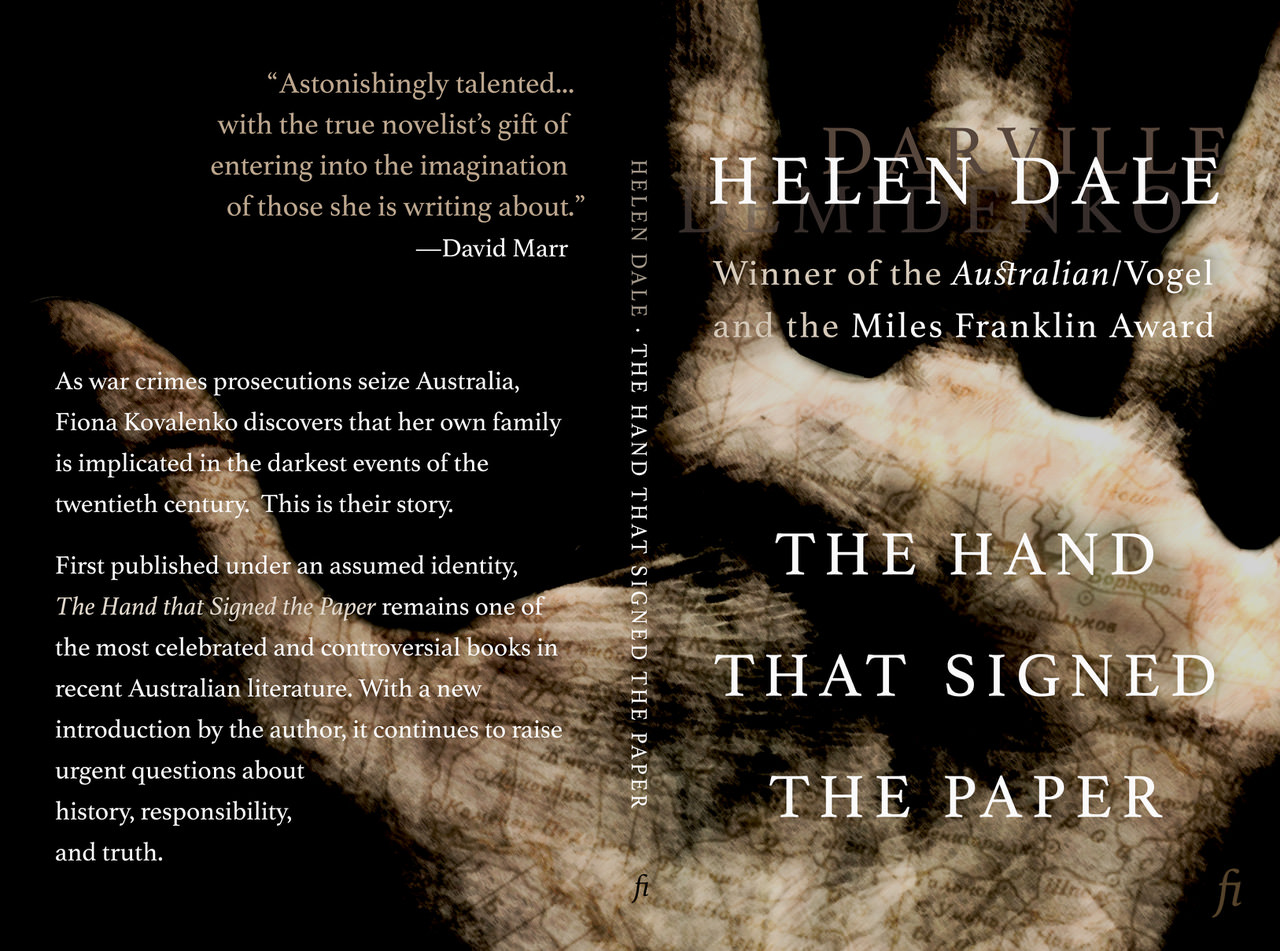

Just over 20 years ago, my first novel, The Hand that Signed the Paper won the Miles Franklin Award, Australia’s premier literary prize. This is an anniversary edition of sorts—although not quite. Had Ligature published it in 2015, it would have appeared while I was working as Senator David Leyonhjelm’s Senior Adviser, and provided an unwelcome distraction from my day-job (as well as a vector for more abusive letters and phone calls to make their way to David’s Sydney Electoral Office; both of us already got enough of those).

However, my publisher explained that it wasn’t ideal to have a Miles Franklin Award winner out-of-print. I was unaware of the extent to which schools and universities were relying on second-hand copies. Worse, there was no electronic version available. I was effectively squatting on my own copyright.

When the book first came out, I pretended to be someone I’m not: Helen Demidenko, from a Ukrainian family with links to the Nazis. In hindsight, trolling the literary establishment (and I mean trolling in the original sense — that is, pulling the wool over) wasn’t the wisest thing I’ve ever done. However, like many trolls, I had a serious point to make: being imaginative is more important for a writer than being from the “right” ethnic background or having the “right” experience.

The criticisms directed at me 20 years ago — after the book won the Miles Franklin Award — and more recently at Lionel Shriver after she argued at the Brisbane Writers Festival that writers should be free to take on other cultural identities, make two claims: “writers should be more representative of the population at large” and “writers should not tell other people’s stories”.

Both claims are incoherent. They are incoherent because literature is not a democracy, it’s an aristocracy — in the old, Aristotelian sense of “rule by the best” — and because novelists are in the business of telling other people’s stories.

It would be nice if making fiction more representative of the population at large by imposing quotas or picking winners from all-women or all-ethnic lists made it better, but it doesn’t. It would be nice if there were a one-to-one relationship between lived experience and literary talent, but there isn’t.

Writing is not the federal parliament or a company’s board of directors. Improving its representativeness will not improve its quality qua literature. There is no guarantee that a novel written about racism by a black author will be better than one by a white author, because “better” in fiction is not a matter of who tells the story but how the story is told.

And just because it’s hard to define excellence doesn’t mean we should give up trying.

For generations philosophers told us there was no such thing as objectivity, but they were wrong: they set the bar too high. No one can satisfy the philosophical definition of objectivity because to do so requires perfect knowledge. Nonetheless, judges, counsel and courts satisfy “the objective test” at common law every day because it is possible to be objective about the facts of the case at hand.

For the same reason, it is possible to define literary excellence while acknowledging that any such definition is necessarily contingent.

By contrast, making politics and corporate boards more representative does make them better (especially with respect to sex, for which there is substantial empirical evidence; there is little evidence that racial diversity improves either political or corporate governance). More women in legislatures mean more jaw-jaw and less war-war. More women on boards make listed companies in particular more profitable.

Literature cannot be reduced to mere political representation: one of these things is not like the other. Making literature more representative will not lower domestic violence rates, or increase Aboriginal life expectancy. Those are political problems, and they require policy solutions. Demanding (and funding, as the Australia Council does) literary representativeness is an extreme example of “pissing in a wetsuit” policy: it feels good, but it doesn’t show.

Many people — particularly those on my side of the political aisle — are fond of suggesting in response to all this that we abolish the Australia Council and let the market decide. However, just as literary excellence is not amenable to political logic, it also can’t be reduced to black ink on a bottom line. Free markets are wonderful, but they also mean bad writing can be popular (Fifty Shades of Grey) and good writing can languish. That’s why establishing an aristocracy of skill and accomplishment that is answerable to neither politics nor markets is valuable.

The attempt to make literature representative — by making the writing profession more representative — also forgets what fiction does.

If you’re an author, your job is to put yourself in the shoes of someone unlike you, someone with entirely different life experiences. People tend to elide authors and characters, but last time I looked Thomas Harris was not a cannibal and Bret Easton Ellis had not murdered anyone.

However, trolling the self-satisfied is akin to some of the scummier public interest litigation getting around, something I only understood after I qualified in law.

There have been recent cases of this type. Gawker was a shitty magazine, and publishing wrestler Hulk Hogan’s sex tapes was wrong. PayPal’s Peter Thiel had a serious point to make about drawing a line between the right to speak and the right to privacy. So he spent millions funding Hogan’s legal action against Gawker, trolling the First Amendment. And he won. Gawker is no more.

Problem is, troll law, both here and in the US, is a bit like being a vexatious litigant. And vexatious litigants are a pain in the legal system.

What I did was, by analogy, “troll literature”, sibling under the skin to troll law. I made my point, but I blew things up in the process.

To be fair, I was not alone in this. I’m still coming to grips with the fact that the 1990s want their politics and popular culture back. Pokemon. Pauline Hanson in parliament. Derryn Hinch famous again (as well as in parliament).

Part of this “everything old is new again” phenomenon concerns section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act, one of Australia’s ‘hate speech’ laws, and also a 90s product. And, yes, I’m glad 18C wasn’t in force when The Hand that Signed the Paper was published (it was enacted in 1995, while my book was published in 1994). It may have been used against me: I was repeatedly accused of anti-Semitism. Indeed, this accusation was far more persistent than anything else thrown my way. And because of my trolling, the defences available in section 18D may not have saved me. A smart lawyer would argue for evidence of bad faith.

Complaints about “cultural appropriation” evince more than a simple wish for equal opportunity publication, however. Such complaints are also about how people are depicted in fiction, and how people would like to be depicted in fiction.

The desire to control how one is portrayed, how one is thought of, is deeply human. It was pervasive when societies were founded on status, not contract. A hint of the past is still visible in those countries with lese-majesty laws, which work to protect a sovereign’s “inherent dignity and honour.”

Nearly all restrictions on speech — including the tort of defamation, section 18C, prohibitions on media reporting of Australia’s offshore detention centre regime and controls on debating ASIO’s “special intelligence operations” — are a black-letter form of the yearning to be thought well of, to be viewed positively.

No police force wants to be written up as the Keystone Kops, no ethnic minority wishes to have the activities of its worst members viewed as representative of the whole, no public figure wants his sexual peccadilloes foregrounded at the expense of everything else he’s ever done.

Hence a willingness to reach for the lawyers.

Unfortunately, law is a broadsword, not a scalpel, when it comes to managing public opinion. Lawyers will freely tell you defamation suits are legal blood sport. Inevitably, the libel finishes up better known thanks to the ensuing court case, while a victorious plaintiff has only money with which to console himself.

Nonetheless, laws constraining how one speaks or writes about others are construed narrowly in liberal democracies, and for good reason: if we all get to protect our “inherent dignity and honour” then speech becomes impossible.

The Hand that Signed the Paper was my contribution to the 90s.

Would I have written it if I’d known the upshot? Probably not. Does it suck like an Electrolux? Probably not. Mind you, your mileage may vary. At least it doesn’t insult you, the reader, by telling you what to think. You have to do that on your own.

Novels can do many things besides entertain, but they cannot make people better. Novelists can do many things besides tell stories, but they cannot make people equal. Those things are not what novels and writers are for.

Those things, to use the common lawyer’s phrase, are “a matter for parliament.”

A version of this article was previously published in The Australian.