Review—Inglorious Empire: What the British Did to India by Shashi Tharoor

All the European powers combined didn’t manage to kill that many people throughout all Asia during their entire colonial histories.

A review of Inglorious Empire: What the British Did to India by Shashi Tharoor. Hurst (March 2, 2017).

In November 2011, Pankaj Mishra, an Indian author, literary critic, and essayist for the Guardian and the New York Times, wrote a scathing review of Niall Ferguson’s Civilisation: The West and the Rest in the prestigious London Review of Books. Ferguson is a pop historian, and his recent polemic depicting Henry Kissinger as an idealist is a corny and ahistorical piece of work for any serious scholar of International Relations. But on one point, Ferguson has been remarkably consistent and fair—that there needs to be a more nuanced assessment of Britain’s Imperial legacy.

Since the Second World War, the prevailing view in academia has been that colonialism was an unpardonable and incomparable sin that plagued the globe for over two hundred years. Any counterpoint to this view is routinely dismissed as pro-colonial and therefore, by definition, racist. Ferguson has argued in several books that colonialism is a much more complicated subject than such black-and-white rhetoric allows. For this, he has been skewered from all sides, most savagely by Mishra in the LRB, who was subsequently threatened with a libel suit. But this episode has done nothing to alter the debate in those areas of academia still dominated by quasi-Marxist postcolonial scholarship.

Today, the postcolonial argument is enjoying renewed support from Shashi Tharoor, an Indian Member of Parliament and one of the brightest and most erudite diplomats the country has produced. With a PhD from Tufts, and degree from St. Stephens, New Delhi, he seems an unlikely bearer of relativism’s polysyllabic jargon. After all, a man who loves cricket, English literature, and Assam tea, and who speaks with a soft upper class RP accent, owes his every success to our colonial legacy, including India’s social structure and so-very-British higher education model.

His book, however, is as interminable a catalogue of opportunistic, revisionist dross as I have read in recent years and that’s saying a lot. I am from India, I currently live in the UK, and I am no stranger to self-flagellating Western postmodernists who blame the West for everything, while enjoying the benefits of its lifestyle, values, and historical legacy. Nevertheless, Tharoor’s book will doubtless be considered a strong rebuttal to the ‘benevolent empire’ thesis, and worshipped by postcolonial scholars, clueless journalists, and activists who will treat it as revealed truth. Any opposition from a Western scholar, no matter how nuanced, will automatically elicit accusations of racism.

Ayaan Hirsi Ali, one of the most vocal critics of postcolonial dogma and cultural relativism, is bizarrely considered to support white supremacy by the Left. If she can be bold enough to challenge conventional wisdom, then in the same spirit, and for the sake of balance, Tharoor’s book also needs to be critiqued by a non-Western scholar. I have been called a ‘Macaulay’s Child’ and a ‘sellout’ to the West already, so I don’t mind explaining why Tharoor is flawed at best and hypocritical at worst. This is not, of course, a defence of colonialism, the brutality of which is well documented and archived (not to mention considerably varied when comparing the experiences of Africa to those of India and China). This is, however, an attempt to bring some urgently needed nuance to the debate to counter conventional postcolonial groupthink.

Tharoor’s book, Inglorious Empire: What the British Did to India, originated from a short lecture Tharoor gave at Oxford, and its main arguments were summarised by the author in an article for the Guardian. Tharoor makes three fundamental claims. First, that India was a singular geographical and anthropological entity, and one of the richest lands on the planet, but that it was thoroughly impoverished by the end of one of the cruelest occupations in Indian history. The Empire, Tharoor argues, bled India dry to fund its own cultural enrichment and industrial revolution. Second, that any contribution by the British to India was for the benefit of the Empire, and not for its Indian subjects. The railways and industries, science and technology were all for the sustenance of British Raj. Third, Tharoor urges Indians to be proud of their own cultural heritage and to be aware of Imperial history and exploitation.

All of these assertions are flawed.

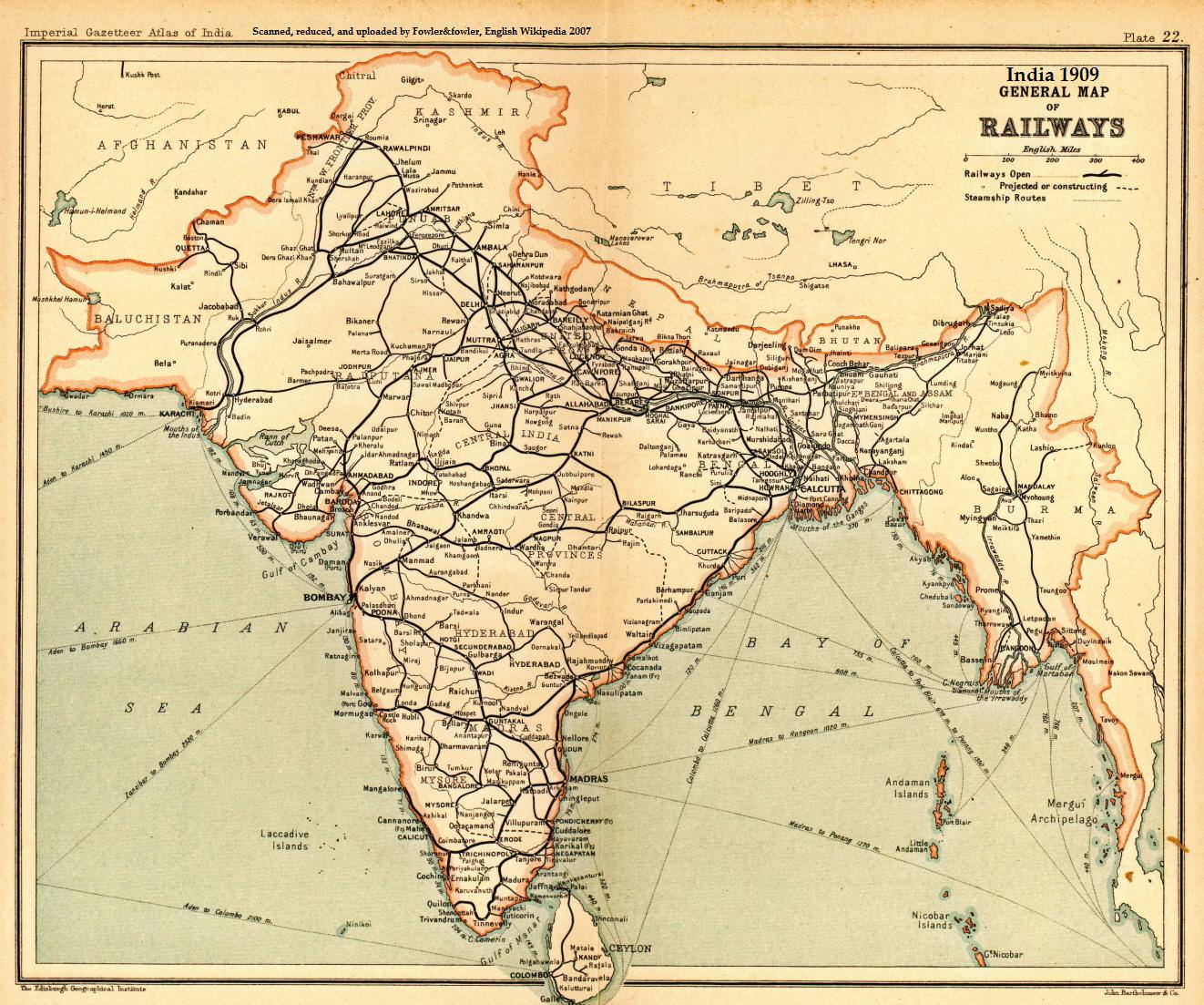

The argument that India was a singular entity, and that Britain ravaged India for her own growth in one of the most rapacious occupations in human history are both fallacious. The concept of a singular state, bound by a unified anthropological identity and defined by post-Westphalian territorial boundaries and statehood, was not present in India before the British united it. In fact, in five thousand years of subcontinental history, only twice was India as we now know it united under centralised rule. The first instance was during the Hindu-Buddhist Mauryan Empire of 322 BCE, and the second was under the Islamic Mughal Empire, which reached its zenith in the late 18th Century. The rest is just a history of different kingdoms battling for dominance, much like continental Europe. All the institutions of modern India—including Parliamentary democracy, the rule of common law and jurisprudence, socio-cultural norms and customs, an independent judiciary, industry, technology, railways, telecommunication and education system—are British imports.

In the last days of the Mughal Empire, and immediately prior to the East India Company’s expansionism, India was so divided that the Maratha Empire, based in what is now Mumbai and Pune, were regularly raiding the Nawabs of Bengal, based near what is now Kolkata. Meanwhile, the Mughal authority in North India was being undermined daily by the Jat, Rajput, and Punjab kingdoms. The South of India was divided between the Nizams of Hyderabad and the Mysore Sultanate. The British didn’t create these divisions, they already existed, based on religious, sectarian, and ethnic identities. The British of course took advantage of these divisions, just like any other prudent expansionist power would have done. Human history is replete with great powers taking advantage of chaos, and it would have been foolish for the British to have done otherwise, especially when they were battling growing French and Russian influence in Asia. But it is simply juvenile to claim, as Tharoor does, that Britain funded her industrial revolution by wringing India dry.

The British industrial revolution started in 16th Century, with massive investments in science, industry, power, locomotives, and, yes, heavy weaponry—the tools which would be needed to contain discontent in India later, as well as to conquer three-quarters of the globe. Indian princes at that time relied upon religious taxes on minorities to fund their military campaigns, and the trade in linen and spices. Serious scientific study was negligible, and often considered anti-religious by both Hindu and Muslim elites. Hindus, especially, considered crossing oceans and large seas to be sacrilegious. If Indians, with our proud history of seafarers and empire in South East Asia during antiquity, never produced any world class explorers during the industrial age, it was because we were constrained by our own religious and anti-scientific dogma during the late medieval era.

Tharoor cites the familiar canard that the Indian mutiny of 1857 was a joint revolt by Hindus and Muslims against the colonial British. This is another piece of post-independence spin. In reality, the mutiny was a revolt by medieval forces opposed to modernity and science against the forces of Enlightenment. Tharoor conveniently omits the fact that the majority of Indians did not rise up against the British; 21 Princely states, alongside the Kingdom of Nepal and Punjab, actively supported the British. The Bengali intellectuals, newly educated in Western science and Renaissance philosophy, who would later lead the actual independence movement, were opposed to the medieval rebels retaking social power.

The revolt and the British victory led instead to the establishment of the Indian Penal Code of 1860, followed by the extremely progressive Ilbert Bill introduced under Lord Ripon in 1883. Tharoor fails (or deliberately neglects) to mention that one of the results of the British victory over the rebels was the Bengal Renaissance, a movement which produced, inter alia, the establishment of science and medical colleges; institutes like the Asiatic Society; universities in Calcutta, Bombay and Madras; and reform movements within the orthodox Hindu and Muslim communities across India.

Tharoor repeatedly claims that the British introduced railways and industries and English language for their own benefit as instruments of colonialism. This is an Ignoratio Elenchi fallacy. Of course they did. But did those things benefit Indians in the long run or not? Tharoor fallaciously tries to quantify the GDP decline of a previously unified non-existent Indian state which he claims was bled dry by the British. But he never tries to quantify the benefits accrued by the social reforms or the advances of technology and industry and science. Using Tharoor’s logic against him, one could argue that India has one of the world’s largest service workforces today in the science, engineering, and IT sectors, and that Indians readily find work in other Anglophone countries ahead of other nationalities because of our ability to communicate fluently. It would be nice if someone were to pay Tharoor to quantify the cumulative advantage of an English education and the taxes earned by the Indian government as a result.

Here’s a little story for Tharoor. One evening, General Sir Charles James Napier, the erstwhile commander-in-chief of the British Indian army, was confronted by a group of orthodox Hindu priests complaining about the prohibition of Sati, a custom that demanded (often extremely young) Hindu widows die on the funeral pyre of their (usually very old) polygamous husbands. This practice was deeply entrenched in the feudal customs of the day. A—s recounted afterwards by his brother William, Sir Charles agreed to allow the Hindu priests to build their pyres in accordance with their customs, but on condition that the murderers were then hanged from a gibbet and their property confiscated in accordance with British customs. How does Tharoor quantify this contribution to Indian society by the murderous British?

Perhaps the most baffling charge made by Tharoor is that the British started the Hindu-Muslim division that later led to partition and bloodshed, and that India was a religious heaven in which everyone coexisted beautifully prior to the Raj:

Large-scale conflicts between Hindus and Muslims (religiously defined), only began under colonial rule; many other kinds of social strife were labeled as religious due to the colonists’ orientalist assumption that religion was the fundamental division in Indian society.

I hesitate to accuse Tharoor of pig ignorance given his stature and qualifications, so the only other logical explanation is that he is intellectually dishonest. One of history’s earliest episodes of unprecedented mass slaughter occurred during the First Fitna (656-661 CE) and the establishment of Ummayad rule. Later, the Abbasid Caliphate supported Mahmud of Ghazni’s yearly raids into India from 1005 CE, reducing the Hindu Somnath temple to dust on a number of occasions. When Persian ruler Nader Shah sacked Delhi in 1739, over 30,000 Hindu inhabitants were slaughtered in two days by the Persian and Kurdish armies. Over the course of the 700 years since Muhammad of Ghori invaded India, over 400 Million Hindus, and over 150 million Muslims died in wars and massacres throughout India. All the European powers combined didn’t manage to kill that many people throughout all Asia during their entire colonial histories. These are empirically established facts, albeit highly inconvenient to Tharoor’s grand anti-Western narrative.

That being said, it must be re-emphasised that colonialism was not benevolent. The British were brutal as well and, notwithstanding phases of liberal reform in India, there were periods of extreme segregation. This is the most serious charge the British face. The Indians, educated and enlightened, wanted to be treated as equals, but there was discrimination even between the Crown’s subjects. Regardless of how many Indians gave their lives in two World Wars and fed the colonial industrial machine, their treatment at the hands of the British was considerably different to that afforded to Australians or New Zealanders or Canadians. Britain wouldn’t have survived a week in the battle against Nazi-occupied Europe if it didn’t have the supportive might of the Jewel in the Crown’s resources and manpower. As Nirad C Chaudhuri wrote, in one of the most poignant paragraphs produced by an Indian scholar about colonial history:

To the memory of the British Empire in India, which conferred subjecthood upon us, but withheld citizenship. To which yet every one of us threw out the challenge: “Civis Britannicus sum,” because all that was good and living within us was made, shaped and quickened by the same British rule.

But that’s history. British Indian history is also Indian history at the end of the day, with the contributions and the exploitations, just like those of the conquests by the Sakas, Hunas, Mongols, Greeks, Afghans, and Persians before them. There was nothing uniquely evil about it.

Tharoor wants Indians to be proud of India. We already are. Proud that we now own the Land Rover and the Jaguar, formerly icons of British pride. Proud to have one of the most successful space programs in the world. Proud to be the globe’s largest supply of brain power and service sector workers, without bombing the West due to pent up sexual frustrations or religious cultism. Proud to be one of the most successful economies of last decade and half which has lifted 21 million people from poverty. Proud that Britain now comes to India to be a trading partner, inviting foreign investment. Proud of our achievements rather than our cultural chauvinism.

It’s better that way. Tharoor might be eyeing a future Prime Ministerial run in India and need these hackneyed 1960s arguments to solidify his pedigree as a patriot. But he can spare us the rage. We middle class Indians don’t have time for that.