Art and Culture

Camille Paglia and the Battle of the Sexes

Women have become angry and defensive as a result of being raised to view men as the enemy.

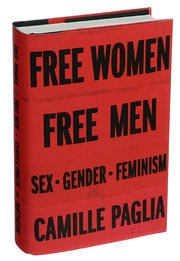

In the opening to what I consider the most important chapter in Camille Paglia’s new book, Free Women, Free Men—Chapter 17: “The Modern Battle of the Sexes”—Paglia writes the following:

As the millennium approaches, we can look back on 200 years of women’s advance in society after the Industrial Revolution. Women all over the world are moving, country by country, into positions of power in business and politics. That progress is inevitable and unstoppable. However, as we survey personal relationships, it is clear that the sexual weather is cloudy and stormy. There is an atmosphere of tension, of suspicion, of mutual recrimination between the sexes which feminism has not helped but in fact materially worsened. How did we get to this point? What prognosis is there for the future?

Unlike Paglia, who’s both a Baby Boomer and a lesbian, I’m a wife and mother who hails from Generation X. I have a daughter who’s 17 and a son who’s 14, so my investment in the question Paglia asks about the future is more personal than I imagine it is for her. And yet this unusual feminist—unusual because she has little in common with the feminist standard-bearers of today—understands so intuitively the plight of male-female relationships I found myself clinging to every word in this chapter.

In it, Paglia sings the praises of authentic, or original, feminism. But that was a long time ago. This movement, she writes, began its descent the moment it turned on men. The feminists of the 1920s and 30s “showed with class and style what it was to be a modern woman, free of the shackles of the past.” But, she adds, they “accepted the achievements of the men of the past . . . There was not the kind of wholesale male-bashing or derisive denigration of men that would later become so entrenched a feature of the second wave of feminism that continues at present.”

Paglia herself was raised in the 1950s, an environment she personally found “unbearable” but which she would later concede made sense for the times, as parents were reeling from the Depression and World War II and merely wanted “something better for their children.”

Still, the social repression of that era didn’t cater to Paglia’s needs. So it isn’t surprising she became enamored with women such as Amelia Earhart, Katharine Hepburn and Germaine Greer—all of whom represented “the new 20th century woman.” Like Paglia, these women were nonconformists who symbolized for Paglia what it meant to be a modern, free-thinking woman.

But in the next sentence Paglia separates herself from the “smug and entitled” feminists of our day who have zero understanding of human nature. All three of these 20th century non-conformist women, writes Paglia, were childless. Translation: they were different from most women. Most women, says Paglia, are biologically wired to procreate—and, foolishly, feminists pretend otherwise. “Feminist ideology has never dealt honestly with the role of the mother in human life.”

In many ways, motherhood is the constant in women’s lives that brings them together in a primal way. Yet women are routinely pulled away from this natural state, this human desire, as though wanting a child or, God forbid, taking care of one, makes a woman a lesser being. I remember my mother telling me, on more than one occasion, that when she attended her graduate school reunion at Radcliffe (in the 1970s), one of the female professors gave a lecture about work and family and said women would need to deal with children as an “intrusion” into their lives.

But the motherhood dilemma isn’t new to feminism. What is new is its glaring animosity toward men. “[Feminist ideology’s] portrayal of history as male oppression and female victimage is a gross distortion of the facts,” writes Paglia. “There was a rational division of labor from the hunter and gatherer period that had its roots not in the male desire to subjugate and imprison but in the procreative burden which has fallen on woman from nature.”

She adds, “Feminism cannot continue with this poisonous rhetoric—it is disastrous for young women to be indoctrinated to think in that negative way about men.”

This is precisely why I wrote “The War on Men” in 2012, in which I described the precarious nature of gender relations. Since the sexual revolution, since Paglia’s time, there has been a profound overhaul in the way men and women interact. Women have become angry and defensive as a result of being raised to view men as the enemy. Armed with this new attitude, they enter relationships with a chip on their shoulder and a sword in their hand, ready to defend themselves against any man who (they perceive) will squash them like a bug.

The problem is that most men have no desire to squash women like a bug. The narrative feminists sold was a lie. “The atrocious exceptions have been used by feminist theorists to blame all men.” writes Paglia. Ergo, women are arming themselves for no reason and as a result can’t find love. Because love doesn’t flow from a well of anger and aggression.

Like Paglia, I too fear for the state of sexual relations. Women today don’t know what they want. They’re torn between wanting freedom and independence, while at the same time desiring John Wayne. But John Wayne is no more. In his place are “men on the leash, intimidated by female demands.”

The irony is exactly as Paglia notes: “the more men accept the feminist line on what women want, the less women want them.”

Therein lies the conundrum of the modern battle of the sexes.