Art and Culture

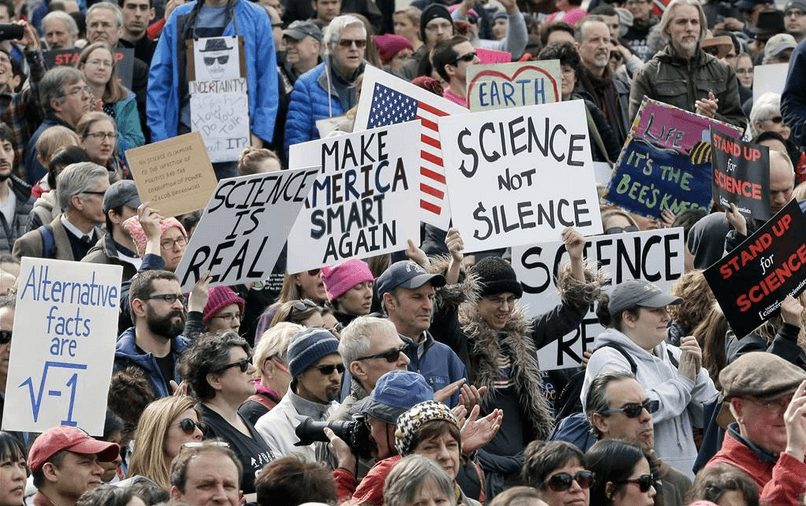

Why Social Scientists Should Not Participate in the March for Science

Why? For one, there is very little political and ideological diversity in the social sciences.

Many social scientists are excited about and poised to participate in the upcoming March for Science, which is being described by the organizers as a “celebration of our passion for science and a call to support and safeguard the scientific community.” I realize that this will be a controversial position, but I believe the best way social scientists can contribute to the March for Science is to quietly sit this one out. I am very much pro-science and share some of the concerns people have about cultural and political threats to science. That being said, in my opinion, the social sciences are currently too compromised to help the cause. Even those who have the best intentions risk doing more harm than good.

Why? For one, there is very little political and ideological diversity in the social sciences. It is true that many academic fields lean left, but this especially the case within the social sciences. Check out Heterodox Academy for details. In many social science departments it is easier to find a Marxist than a Republican. In fact, it is quite common for social sciences departments to have no Republicans at all.

Many have criticized social science research for being ideologically biased and, frankly, many of these criticisms are fair. For one, social scientists have spent decades using sloppy empirical methods, or no methods at all, to make the case that conservatives uniquely possess a number of undesirable personal characteristics (e.g., prejudice and intolerance). However, as I discussed in an article for Scientific American, recent studies reveal methodological flaws of past research and show that liberals are no more tolerant or nondiscriminatory than conservatives.

Moreover, a number of the psychological concepts social scientists and activists have used to support social justice-oriented interventions and policies have not stood up well to empirical scrutiny. Take, for instance, the concept of stereotype threat. Psychologists proposed that female math performance is undermined by the existence and situational awareness of the stereotype that women are bad at math. However, the stereotype threat explanation of women’s math performance has failed multiple replication attempts. Meta-analyses have offered no support for the idea. And the original supporting research has been widely criticized as having many methodological and statistical problems. Still, many social scientists, activists, and college administrators continue to teach and champion the idea.

Unfortunately, the stereotype threat example is not an anomaly. The concept of unconscious or implicit biases as measured by the implicit association test (IAT) has also received considerable criticism. Many social scientists, activists, college administrators, and science journalists, have made empirically unsupported or exaggerated claims about the predictive power of the test while neglecting to mention or consider its many problems and limitations. More generally, the term unconscious bias is carelessly and unscientifically employed by many, including social scientists who should know better, to explain outcomes they find personally undesirable.

The microagression concept is another example. Again, many academics, activists, and college administrators are enamored with it, without scientific justification. Psychology professor Scott O. Lilienfeld summed it up perfectly with the title of his very thorough article – Microaggressions: Strong Claims, Inadequate Evidence.

The truth is, some social scientists, though certainly not all of them, and many social activists and journalists have weaponized the social sciences for ideological warfare. This has created quite a mess. One way social scientists can stand up for science is to clean up this mess and dedicate ourselves to fighting ideological bias within our fields. We have a lot to offer and much of our research is very good and has little or nothing to do with social and political alliances. However, we cannot afford to ignore the very real threat that ideological bias poses to the empirical social sciences.

In addition, social science has its own internal “war on science” problem that few seem willing to confront. This problem results, in part, from the reckless use of the social science label. Not all of the social sciences use or support the scientific method. Even within a given field there is often a division between actual scientists and scholars who do not take a scientific approach to their research. Take, for instance, the field of sociology. There are certainly many empirical sociologists doing high quality empirical research. However, a sizable part of the discipline is part of the postmodern or social constructionist movement that rejects the use of quantitative methods.

I have been arguing with postmodern sociologists since I was a graduate student over 15 years ago. (See my interview for more details on this issue). The basic point is that postmodernists reject the scientific method. And their research methods are fundamentally ideologically biased. Moreover, postmodernists advocate blank slate theories of human cognition, emotion, and motivation that are at odds with decades of very sound empirical research from biology, cognitive neuroscience, evolutionary psychology, and personality psychology.

Postmodernists also directly attack the scientific enterprise. Consider, for example, the “research as rape model” presented in sociological textbooks such as An Introduction to Sociology: Feminist Perspectives. The model proposes that conducting scientific research using human research participants is a form of research rape. Wait for it. The scientist is violating the research participant, taking something (data), and giving nothing in return. This is, of course, argued to be the result of an oppressive, patriarchal, and colonialist approach to science.

Science is biased

Science helped establish modern borders as a colonial institution

Science was funded by the MAAFA, it has a color & creed https://t.co/lTPFhoqJcy

— PeoplesScientist✊? (@Hood_Biologist) January 27, 2017

Professors in postmodern fields such as gender studies are actively teaching ideas that are more conspiracy theory than scholarly research. If you want to laugh or perhaps cry from seeing what postmodernists are up to in the social sciences, follow the New Real Peer Review @RealPeerReview on Twitter. Many academics focus on attacks on science from politicians and the general public without realizing they are being flanked by postmodernists from within the academy.

In addition, postmodern social scientists and their inspired disciples are using these ideas to serve social justice goals. This is a serious problem for a number of reasons. Most notably, many of the postmodern theoretical positions are at odds with decades of research on how to reduce prejudice and improve intergroup relations, and could thus cause harm to members of the marginalized groups they are supposedly seeking to help.

How can we social scientists make a stand for science when there are clear examples of ideological bias in our fields and some members of our fields are wrongly using social science to support political agendas? How can we make a stand for science when we have many anti-science postmodernist colleagues among our ranks? If we won’t even defend science within the social sciences, how can we defend it to the public or our elected officials?

I know people want to be part of the movement and make a public stand for science. I also know that many social scientists can fairly argue that their research is scientific, has important implications for the public, and is not ideologically contaminated. I feel this way about my own work. That being said, we need to think rationally and tactically about what is best for science. Perhaps we would be better off sitting this one out and doing the slow but important work of reducing ideological bias in our research, fighting the tendency to weaponize social science for ideological and political purposes, and challenging the non-scientific and sometimes anti-science scholarship that is being sheltered within the academy. This work might not be as fun as the collective catharsis of a public march, but it could have a much longer lasting and rehabilitative effect on the social sciences and how they are viewed by politicians and the public.

More generally, it is not clear to me that the March for Science is a good idea in the first place. There are important questions worth considering. Is a march the best way to communicate the concerns of scientists and persuade people these concerns are legitimate? Will the organizers be able to control the message and keep participants from injecting politics into the march unnecessarily and in a way that ends up damaging the cause? Will anyone besides those marching even care? I worry about these issues as well. At a minimum, we social scientists could help by recusing ourselves.