Canada

Students, Sex, Social Media and Why the Steven Galloway Affair Is so Murky

There’s a solution, but it’s not one that most feminists want to hear.

On a frigid night a few years ago, a friend dragged me to an event at a popular Montreal bar. Students of a local graduate program in creative writing were giving a reading.

My friend and I sat close to them. I watched as pitchers of beer came and went and the students danced attendance on an older man, perhaps an instructor or organiser of the event. As the night went on and inhibitions were lowered, evidence of unruly feelings became obvious. Most creative arts departments are proverbial hothouses as far as egos go and this group was no exception. They were living proof of that punk axiom: eventually, love would tear them apart. The emotions I saw guaranteed it.

Although I teach literature, I’m wary of university creative writing programs: they may be prestigious and even profitable, but I suspect they are more about buying access to agents and less about incubating talent. The students I heard that night read about relationships — with some texts directed at others in attendance — and yet none read anything exceptional. Yes, they were young; yes, their work was embryonic and might improve. But that didn’t dispel my fear that they were being duped by a university experience that was misleading by its very existence. They believed they were members of a coveted cadre and destined for literary glory; a statistical improbability if there ever was one.

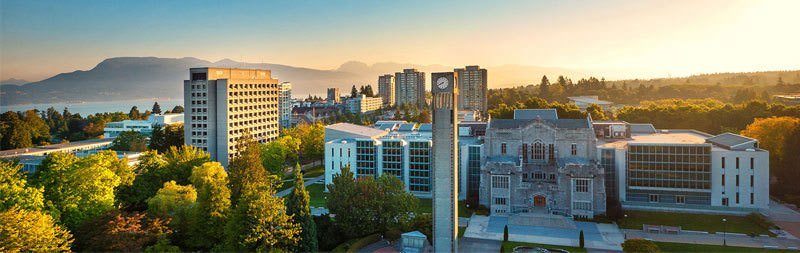

So it’s not surprising that the creative writing program at the University of British Columbia, another hothouse, imploded last year over allegations of sexual abuse and misconduct. Foregrounded is the alleged bad behaviour of the former department chair, Steven Galloway, acclaimed Canadian novelist, and backgrounded is a program as rife with contradictions as the one I saw that cold February night. That conversations about Galloway are taking place without acknowledging the complexities of his work environment is bizarre, a bit like summarising Robinson Crusoe and failing to mention it takes place on an island. The context is important because creative communities often come with hazards: even the most level-headed students can enter them and can appear to develop borderline personalities overnight.

The scuttlebutt, where UBC is concerned, is that there was none, apart from an announcement that “serious allegations” had been made against Galloway and he’d been suspended for the “safety” of students, words cryptic enough to become as irresistible as click bait. Allegations of sexual abuse — assault and harassment — did surface eventually but these came from the department’s most disaffected students and barely qualified as serious complaints. However, they arose in an atmosphere primed for hysteria: a previous case of harassment, concerning a PhD history student, had been handled too slowly for some in the UBC community and investigative journalists, from the CBC’s Fifth Estate, took aim at the university’s administration. It’s likely their coverage, and the negligence it claimed, had more to do with Galloway’s treatment than any bad behaviour on his part.

What happened? As that previous case was being decided, a letter was circulated, criticising the university’s handling of sexual abuse and assault. It seems to have come from Galloway’s main complainant in the case against him, a former teaching assistant in the creative writing program, a woman who is now alleging Galloway raped her. For his part, he admits they had a two-year affair that started in 2011 and did not end well. It’s unclear whether she wrote the letter or whether she simply circulated it with the intention of getting his attention. (Sources on this issue differ.) Whatever the case, it worked. Galloway saw the letter, recognised its intent and called the woman who refused to speak to him. Since both had been in other relationships during the affair, they had kept quiet about it. Their secrecy made sense at the time but was eventually Galloway’s undoing.

The sum of the complaints led to an independent investigation led by retired Judge Mary Ellen Boyd. She concluded that of the many accusations against Galloway, only one was credible — that he’d had an undisclosed sexual relationship with a subordinate. Still, Boyd concluded that Galloway’s actions irreparably damaged an atmosphere of trust and he was subsequently fired.

While his union is grieving on his behalf, Canadian authors, led by luminaries Margaret Atwood and Joseph Boyden, wrote an open letter to UBC asking for more transparency in the process that led to Galloway’s firing. The consequences were predictable: hashtag campaigns against Atwood, Boyden and other signatories soon appeared. Then for no apparent reason, Boyden’s claim to aboriginal ancestry was challenged in a Canadian magazine.

The problem with all of the accusers is credibility. The main complainant did not go directly to university administrators whose job it is to help students in crisis. Instead, she communicated with faculty members long after the fact, suggesting they consult other students to collect evidence of Galloway’s guilt. The upshot is that two other students, both of whom ended up being complainants themselves, did their own detective work. One distributed a secret memo to other students asking them to come forward if they had any complaints about Galloway; the other, who was also an employee of the University, used her position to dig into his use of department finances. Both students did this clandestine evidence-gathering under the direction of one of Galloway’s colleagues. That colleague was the same one who insisted that he be taken to a psych ward after he received an email about the accusations against him. He was in the U.S. at the time, giving a talk at another university.

As the letter by Atwood and Boyden made clear, no criminal charges were ever laid against Galloway. Although there were complaints about bullying and favouritism, those charges are endemic to creative writing milieus. For students, the perception of being in a group of up-and-coming writers is bound to be matched by high levels of exquisite sensitivity, levels that would render their criticisms dubious. This is in fact what Judge Boyd determined.

Galloway’s firing is the latest in a series where extra-legal channels like social media and university administrations are being used instead of courts to bring alleged rapists to justice. Occasionally cases do go to court, but not before the “victim’s” story has been widely disseminated via social media. These accusations are becoming depressingly familiar: they are launched by ex-dating partners, are evidentially weak, and accusers either collude or are drawn into the fray via the bandwagon effect.

There’s a solution, but it’s not one that most feminists want to hear.

No one is saying it, but had these women challenged their alleged rapists, they would have challenged their relationships too. Porn actress Stoya, who alleges she was raped by her ex-partner, James Deen, could have said to him, “I don’t like what you did. I don’t think we should continue to see each other.” The women who dated and then accused Canadian broadcaster Jian Ghomeshi of assault could have refused to see him again and not written love letters to him afterwards.

Yet traditional paradigms of cognitive dissonance dictate that these women, just like Galloway’s accusers, will not admit liability. In fact they will insist, even more loudly, that they are faultless. But the contagion of these incidents is telling and the emotional heft of these narratives is waning. Scepticism is a good response to women who confect outrages, but the cumulative effect still casts doubt on others who have genuinely been raped.

For some of us, that’s just too high a price for vengeance.