Art and Culture

Review: Hillbilly Elegy — J.D. Vance

Through it he tells the story of hillbillies, impoverished immigrants who came from Scotland and Ireland in the eighteenth century to settle in the American south.

A review of Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis, by J.D Vance. Harper, (June 28, 2016) 272 pages.

Hillbilly Elegy is a memoir written by young American lawyer, J.D. Vance. Through it he tells the story of hillbillies, impoverished immigrants who came from Scotland and Ireland in the eighteenth century to settle in the American south. It’s also an apologia of sorts, one that may explain why Donald Trump, that inveterate carnival barker, has achieved political prominence. At a time when flame wars equal public discourse, Vance’s calm, thoughtful analysis is a welcome respite. It reflects on the current presidential race, revealing it for star-spangled spectacle and bun fight it’s become.

That’s because Vance’s exhortations for better behaviour are handed out equally. Liberals who dismiss the working classes — Clinton’s “deplorables” come to mind — are chastised along with the unemployed, able-bodied neighbours who keep hitting up Vance’s grandmother for cash. Conservative businessmen, who moved their midwestern factories to the third world, are criticized along with the drug lords who moved their empires into the vacuum left behind. That all these groups fit comfortably into the scope of Vance’s analysis tells us the underlying social problems are bigger than most pundits are allowing for, a state of affairs that has facilitated, arguably, the rise of Trump and the success of Brexit in the U.K.

Vance’s transition from hillbilly to Yale graduate provides a singular portrait around which his broader observations unfurl. As the son of a mother distracted by multiple partners and addictions, his early years were predictably unsettled. His colourful extended family stepped in, and they loved him unconditionally but weighed him down too, making a successful future for him tenuous: it’s clear Vance’s fear of outpacing them was as powerful as the low expectations holding him back. However, his grandfather’s sudden decision to quit drinking (and his grandmother’s decision to quit bickering) gave him just enough support and perspective to see his own potential.

So it’s as one of the upwardly mobile that Vance maps the growing dissonance between his country’s working and middle classes. Of Obama he says:

He is brilliant, wealthy and speaks like a constitutional law professor — which, of course, he is. Nothing about him bears a resemblance to the people I admired growing up: His accent — clean, perfect, neutral — is foreign; his credentials are so impressive, they’re frightening.

Obama’s foreignness places him so far above Vance’s community that not only does the idea of holding office seem futile, just gaining the goods to get there is frightening. Vance argues that it’s this impossible distance, and not racism per se, that breeds dark and persistent theories about Obama’s origins, those that assert he is non-American or Muslim or has ties to Islamic extremists. Just as the Greeks needed gods to explain their mysteries, America’s underclasses need a narrative, however grotesque, to explain their lack of options. The finer points of free trade might account for their economic realities, for example, but they don’t account for why they’ve been so thoroughly abandoned by their government.

And it’s abandonment — along with the feeling the worst has already happened — that nurtures a social inertia that allows America’s poor to choose disaster casually, so casually in fact that even Vance, who grew up among them, is troubled by what he’s seeing.

Too many young men immune to hard work. Good jobs impossible to fill for any length of time. And a young man with every reason to work — a wife-to-be to support and a baby on the way — carelessly tossing aside a good job with excellent health insurance. More troublingly, when it was all over, he thought something had been done to him. There is a lack of agency here — a feeling that you have little control over your life and a willingness to blame everyone but yourself.

Vance frequently reminds us that he does not believe in identity politics, especially of the sort that excuse consistent poor judgement. But his frustration with both high and low agency Americans, and the unwillingness of both groups to work together, and toward improving living standards, is clear: the U.S. has a problem opening doors for those who are ambitious and pulling up bootstraps for those who are not; harmonizing the two, Vance believes, needs leadership stronger than the kind Obama has provided. He also believes churches have a role in economic welfare — an unusual and perhaps provocative idea — but it’s an observation that makes sense given his diffident faith in Americans’ capacity to help themselves.

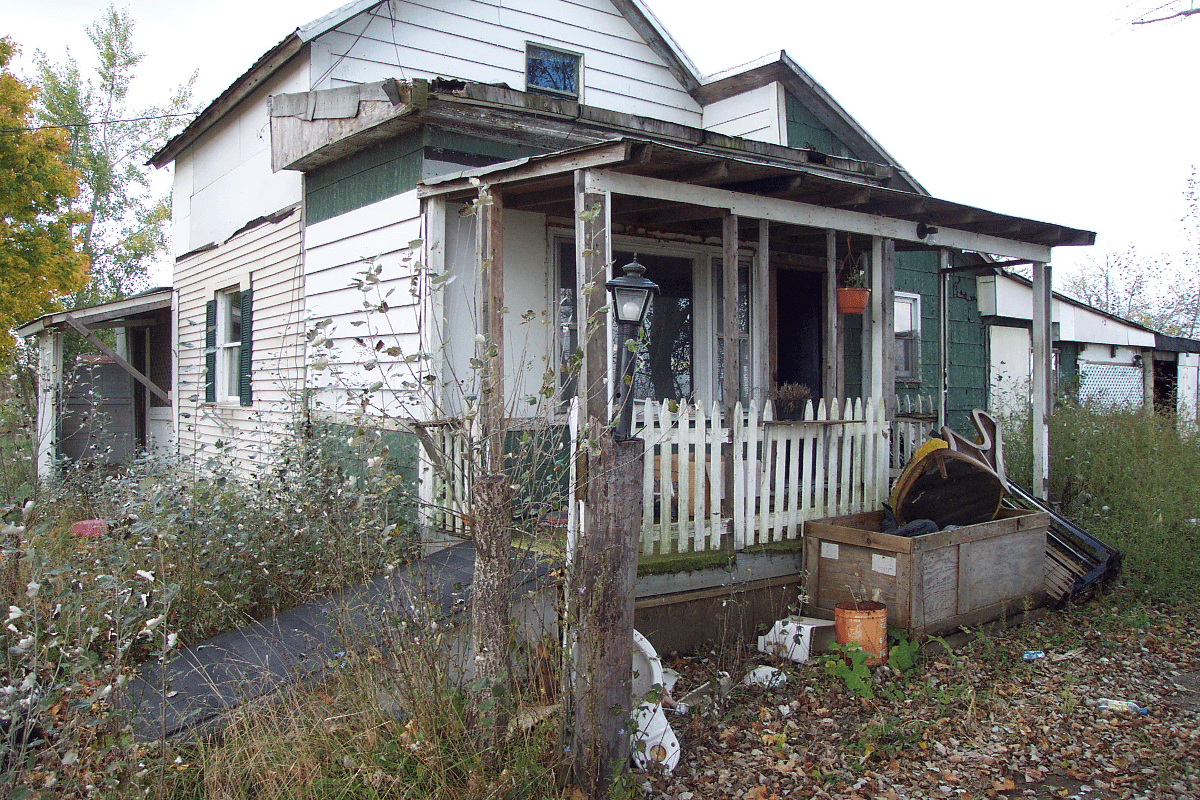

What is most striking about Hillbilly Elegy is Vance’s profound attachment to the idea of personal accountability. Being raised by a mother addicted to chaos will do that to those who survive, and Vance is no exception. His memoir closes with an aching anecdote where he describes cobwebs adorning the reception area of a gone-to-seed hotel. This is where he’ll advance a week’s rent to save his mother from the street yet again. The abiding pain he feels being a parentified child is obvious. What this tableau, complete with a toothless clerk, captures, is the generational costs of economic hardship, drug addiction being just another bad outcome.

In the end, Vance’s unfashionable belief in accountability, hard-won as it is, is hardly a flaw, especially in these pandering, narcissistic times. His grief is real and potent and amounts to an emotional experience that makes safe space mavens look just as ridiculous as they surely are. Moreover, reading a book where a practical sensibility becomes a touchstone the writer keeps returning to, however far afield his observations may go, is a pleasure and is what lends Elegy its vitality. As Vance himself admits, his book is a memoir of a young and not an old man, but that hardly matters: it’s powerful, necessary and graciously untouched by self-indulgence.