Hypothesis

Authoritarianism is a Matter of Personality, Not Politics

Because democracy reflects the will of the majority, extremists will never win a fair election.

There are people who are attracted to the prospect of oppressing others. Authoritarian personality characteristics form a continuum, from low to high, in the human population1. This discovery means that approximately 16% of the population possesses a personality profile that is significantly more authoritarian than average.

As with so many breakthroughs in personality research, the person who initiated scientific explorations of this topic was Hans Eysenck. Eysenck’s interest in the personality predictors of political extremism was perhaps forged by his experience of growing up in pre-war Germany2. It was, therefore, a central irony of Eysenck’s life that he fled from Germany to escape fascism in the 1930’s, only to fall foul of communism once in Britain3.

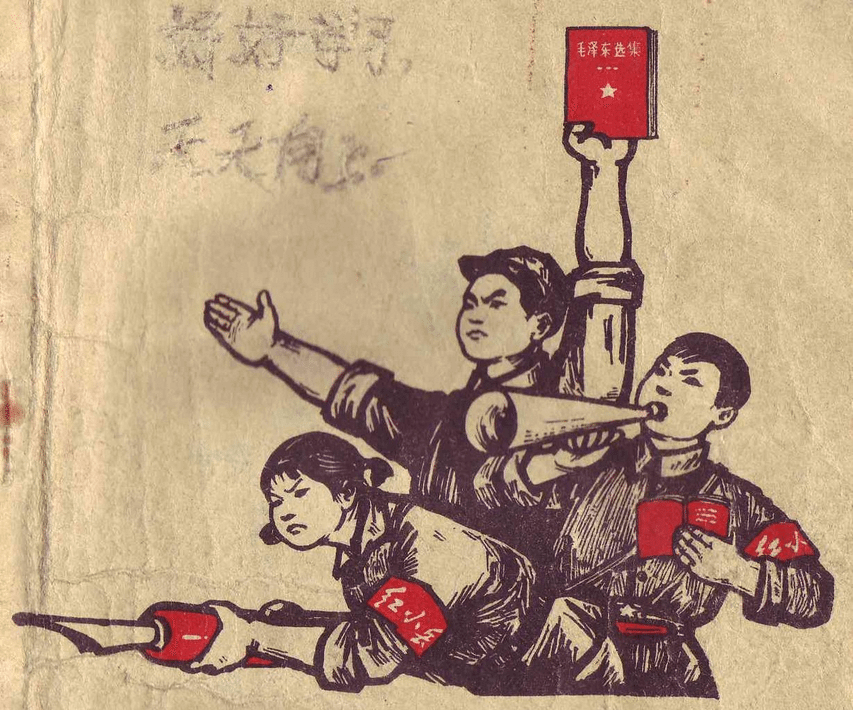

In a convergence of life and science, this irony did not escape Eysenck’s attention and he began researching the personality correlates of political extremism4.The crucial insight stemming from Eysenck’s work is that the specific flavour of extremism that people with highly authoritarian personalities support is immaterial. They merely gravitate towards whatever regime will give them a flag of convenience to act out their oppressive urges.

In the 1970’s in Europe it was such entities as the Red Brigade or the Baader-Meinhof Gang. Now it happens to be Islamic extremism. We have seen this flag of convenience tendency illustrated in recent years by the discovery that many Jihadists come from middleclass Westernised, Muslim families and some have even turned out to be of white, Christian origin.

Looking further back in history, we can see Eysenck’s discovery illustrated even more clearly by evidence that, if one extremist regime collapses, its supporters readily switch their allegiance to another extremist regime, even if its dogma is opposite to that of the regime that they previously supported. Perhaps the most vivid illustration of this flip-flopping tendency amongst extremists occurred in Hungary following the end of the Second World War, when the fascist Arrow Cross Party that had ruled Hungary from 15th October 1944 to 28th March 1945 was replaced by a communist regime. What is notable about this event is that individuals who were previously card-carrying members of the Arrow Cross Party joined the Hungarian Communist party5. These were the same people, carrying out the same oppressive behaviour for both regimes, but in the process of doing so, had reversed from one end of the political spectrum to the other.

The key to a harmonious society is therefore not to crack down on one flavour of extremism, because its supporters will see the way the wind is blowing and will backflip in their allegiances, joining in the crackdown on their former comrades.

Instead the key is that extremist regimes, whether communist, fascist or religious are always dictatorships. This tells us there is something special about democracy that prevents extremists gaining power. My guess is that because political extremism appeals to a minority whose personality attributes mean that they enjoy oppressing other people, it doesn’t appeal to the majority, who possess average personality profiles and thus are not especially attracted to oppressive behaviour.

Because democracy reflects the will of the majority, extremists will never win a fair election.

Therefore I suggest that the take home message from the recent atrocities in Paris is that we must do more to encourage the spread of democracy around the world, starving extremists of their authoritarian power base.

References

- Ludeke, S. G., & Krueger, R. F. (2013). Authoritarianism as a personality trait: Evidence from a longitudinal behavior genetic study. Personality and Individual Differences, 55, 480-484.

- Corr, P. J. (2016a). Hans Eysenck: A Contradictory Psychology. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Corr, P. J. (2016b). The centenary of a maverick: Philip J. Corr on the life and work of Hans J. Eysenck. The Psychologist, submitted.

- Eysenck, H. J. (1954). The Psychology of Politics. London: Routledge and Keegan Paul.

- Borhi, L. (2004). Hungary in the Cold War 1945-1956. Budapest: Central European University Press.