Art and Culture

Our Generation Did Not Invent Political Correctness, But We Can Fight It

The problem with P.C. is that it constrains the questions that we feel we can ask both of ourselves, and our superiors. It allows orthodoxy to creep in (as it always does).

Political correctness is not a new phenomenon. The fact is that many dangerous questions are currently walled off by the baby boomers who dominate our universities (and large sectors of the media). Today’s culture war likes to scapegoat young people for the rise of the illiberal Left, but the responsibility really lies with the generation who came before us.

Each one of us has the ability to generate a hypothesis. A hypothesis simply comes from asking a question about the world and then using our imaginations to answer it. Almost every advance in human history first came from a person willing to look at the world, or the status quo, from a different angle. But if questions and hypotheses are going to have any impact they must be articulated. Questions have to come out of our minds and into the world around us.

The problem with P.C. is that it constrains the questions that we feel we can ask both of ourselves and our superiors. It allows orthodoxy to creep in (as it always does). There is, however, a continuing perception that arguments against P.C. are only made by those wishing to go around calling people racist or sexist names. The question is often asked: what exactly is wrong with P.C. if it makes us more civil? The short answer is nothing. If that were all P.C. were about, no-one would have a problem with it at all.

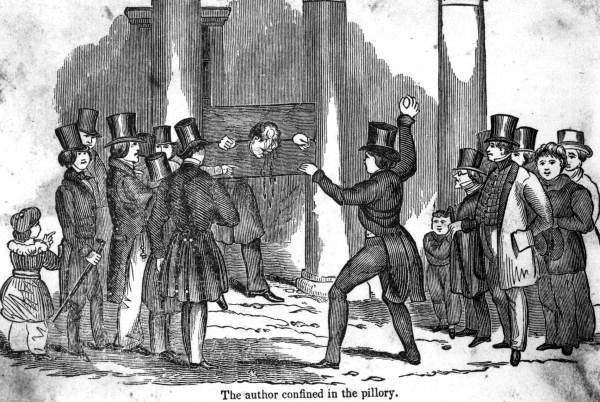

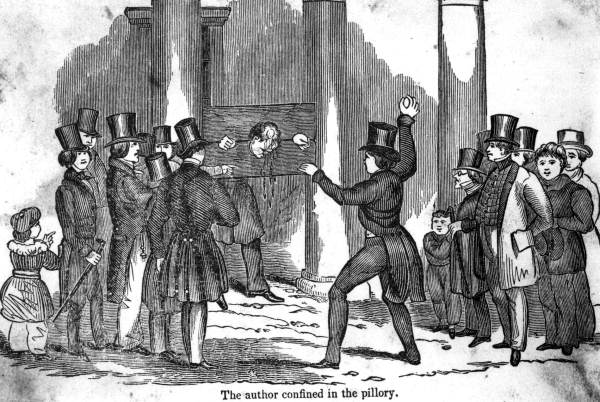

If P.C. meant that fewer ad hominem insults were used in public discourse, intellectuals across the board would support it. If it meant that individuals were not clapped in the stocks in sadistic public-shaming campaigns, P.C. would be progressive. But in practice, those who enforce P.C. standards seem to specialise almost exclusively in ad hominem attack. Twitter mobbing, which quite literally destroys people’s reputations and livelihoods, is the apotheosis of P.C. justice. There is nothing civil or redeeming about it.

After the transformation of society brought by the 1960s, a cohort of sentimental liberals naturally flocked to academia. Many of them set up shop in the humanities and social sciences and spread both postmodernism and blank slate fundamentalism (the ideological resistance to biology, genetics and evolution) far and wide throughout the academy. These two mutually reinforcing ideologies have had a massive effect on scholarship and the wider culture.

It would be prudent for us to remember that of the young people who police language and thought on campus today, many have not yet left home; their privilege has effectively kept them in a state of intellectual neoteny. While the political movements that their parents were involved in were creative, aspirational and good-hearted, many of these movements have now ossified into the most brittle of orthodoxies. P.C. students on campus today are simply foot soldiers for their parents’ ideologies. And before we attack young people for being censorious and priggish, we should remember that this kafkaesque political baggage is what this generation has to bear.

In 2005, when the president of Harvard, Larry Summers, hypothesised that women’s under-representation in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) might have something to do with men’s greater variance in IQ scores, his hypothesis was declared untenable. Touching on two taboos at the same time—intelligence research and sex differences—meant that he was met with the writhing apoplexy of the self-righteous mob. The scientific evidence was ignored, very few, even in the academy, defended his right to hypothesise, and he lost his presidency.

P.C. crusaders in the academy also have a long tradition of obstructing empirical work into sex differences. One psychologist repeatedly labels research looking at brain sex differences as “neurosexism” and “neurotrash.” And discouraging research into brain sex differences has very real consequences. In 2013, the drug administration of the U.S., the FDA, issued a statement instructing dosing for popular sleeping pills to be halved for women. Their decision implied that women had been overdosing on sleeping pills for nearly twenty years. Neuroscientists such as Larry Cahill, have described the situation as pitiful. P.C. dogma has stymied research into female neurobiology for years.

It is not my generation that is responsible for this kind of groupthink. Yes, original feminism was creative and brilliant in extending principles of humanism and universalism to women. But my generation were not bequeathed a political movement with an Enlightenment impulse. What we inherited was the intellectual equivalent of a dead carcass. Those of us born in or after the 1980s, who studied humanities at university, were told by our professors that “there is no universal truth.” We either dropped out—or became indoctrinated into a cult of epistemological nihilism. My generation did not bring the rot of postmodernism and blank slate fundamentalism into the academy. How dare the wider culture blame us for this? We are the generation left with liberal arts educations that have been trashed from the inside out.

It might serve us to remember that the enforcers of dogmas today would have been the enforcers of dogmas yesterday. Those who went after Dr Matt Taylor of the Rosetta Mission for his shirt, would have happily brought Galileo before the Inquisition—and they would have thought it was for his own good. Whether they are warriors for God, or warriors for Social Justice, the moral certainty of holier-than-thou crusaders tends to remain the same.

Today’s “Stepford Students” are indeed disconcerting. But we ought not forget where and with whom their belief system originated. The Old Guard will eventually leave their postings in the academy (and the media) and it is up to us to make sure they take their P.C. dogmas with them. Of course, the baby boomers have made wonderful contributions—in art, culture, technology and science—but we should feel free to leave their orthodoxies, taboos and political baggage behind.

We did not invent P.C. but we can fight it. The first step is to drop our parents’ blank slate ideologies, including postmodernism, into the dustbin of history. The second step is to start asking questions, even if they offend. The third step is to get them down on paper (or the computer screen) and circulate them with other heretics. We all have the ability to generate hypotheses, and hypotheses are the engine of progress.