Blog

Welcome to Canada, Where Everyone’s a Génocidaire

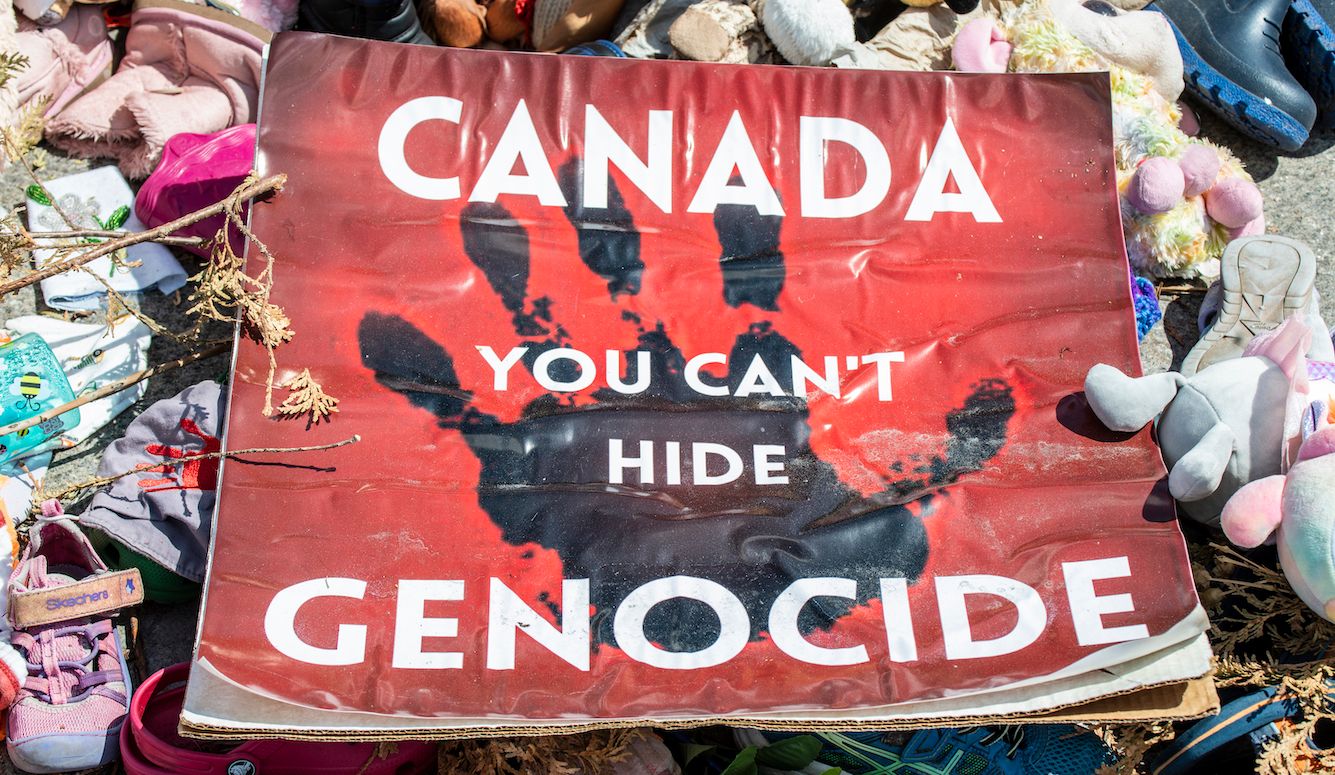

Canadians are being told that they’ve perpetrated multiple genocides. So why aren’t their leaders being tried at The Hague?

The French noun génocidaire—indicating a person who’s participated in a genocide—has no direct English equivalent. That will need to change, however, because every leader in Canada’s history has now effectively been declared a génocidaire, as have an uncountable number of cabinet ministers, government employees, religious officials, and educators. And it seems impractical for us to rely on a foreign word to denounce these criminals as we march the living specimens off to The Hague while stripping the dead of their reputations and honours.

On October 27th, a parliamentary motion demanding that the federal government “recognize what happened in Canada's Indian residential schools as genocide” passed by unanimous consent. To be clear, the resolution’s author, MP Leah Gazan, did not qualify the word “genocide” with “cultural,” as the country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission had done in 2015. It’s just genocide, full stop. To such extent that this resolution is taken seriously, anyone who helped oversee, fund, or operate Canada’s residential-school program shall now be classified as a participant in genocide. And since Canada's residential schools have been operating since before Canada came into existence 155 years ago, this list would include every prime minister who served up to 1997, when the last residential school was closed—i.e., all 23 of Canada’s PMs except Paul Martin, Stephen Harper, and the incumbent, Justin Trudeau.

But even that latter trio can’t escape the génocidaire designation. Back in 2019, Trudeau confessed to a separate (and apparently “ongoing”) genocide when he acceded to conclusions presented by the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG). This means, for those keeping score, that Pierre Trudeau (1919–2000), Justin Trudeau’s prime ministerial father, is implicated in not one but two genocides, while Justin is guilty of just one. But this is not the final tally: Given Canada’s current political climate, newly discovered genocides are no doubt in the offing.