Space

The Artemis Project

The race is on to build a base for permanent human habitation on the Moon.

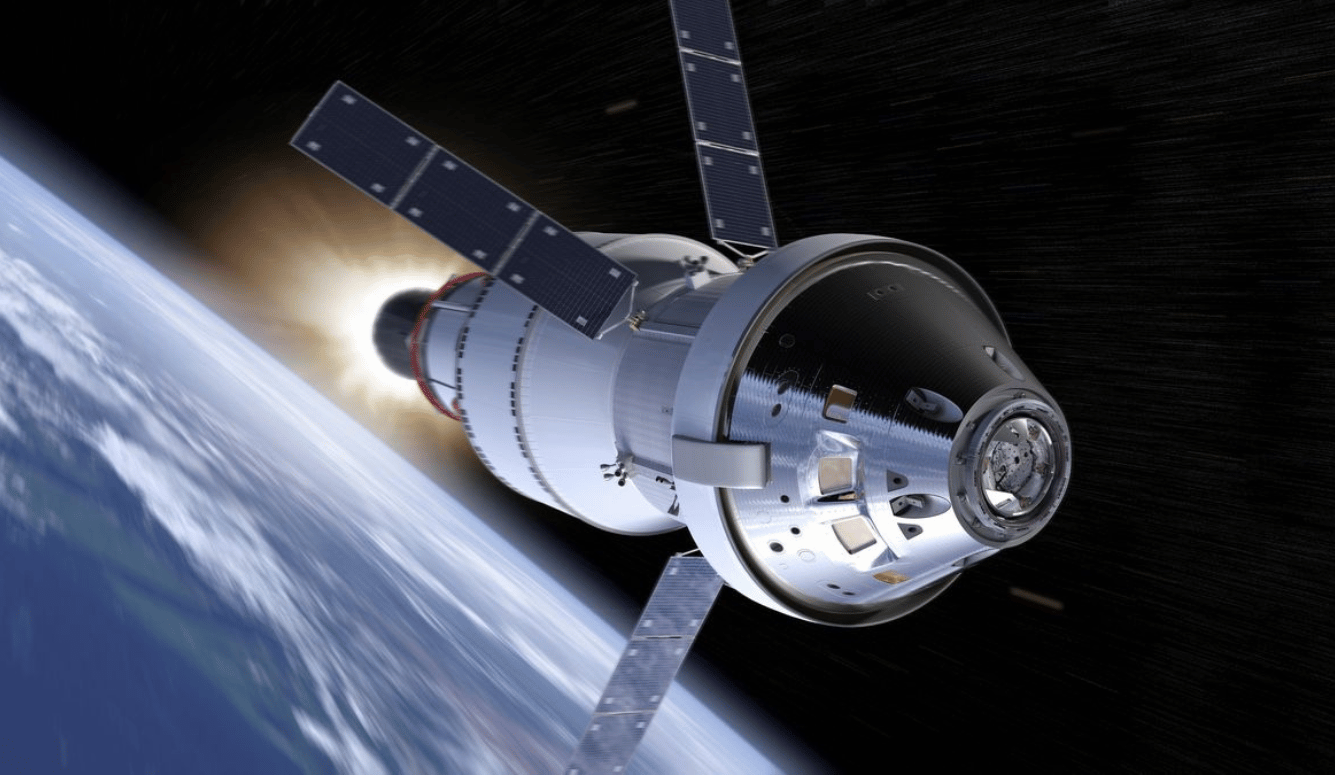

Next month, four astronauts will blast off from Kennedy Space Center on the Artemis II mission to the Moon. This is the first time anybody has travelled beyond low-Earth orbit since 1972. The spacecraft, an Orion capsule named Integrity, will fly on a free-return trajectory, looping around the far side of the Moon before returning directly to Earth.

It is worth visualising the distance involved in this flight. Think of a typical 30cm diameter globe of the kind you might have at home. On this scale, the ISS orbits in a circle just 1cm above the surface. The 2024 Polaris Dawn mission set an altitude record for Earth orbital flight at 3cm. At its furthest, when it passes behind the Moon, Artemis II will be about 9.5 metres from this globe—a distance of about 1.3 light seconds. Light—and other forms of electromagnetic radiation such as radio waves—will take 1.3 seconds to reach the crew at their furthest point, and you will be able to hear this delay in their conversations with mission control. At this point it will take four days to return to Earth. There will be no way of getting home faster. The crew will be on their own and totally reliant on their spacecraft for safety.

Against the backdrop of current world events, the flight of Artemis II might not seem of great significance. The United States is in the grip of severe civil unrest, and the political elite in Europe are struggling with an increasingly angry population who have been demanding change. Superpowers are facing off against each other, and smaller nations are being crushed under the boots of larger ones. This could also describe the situation in 1968—the year Apollo 8 first took humans to the Moon.

When the crew of Apollo 8 captured the famous photograph of the Earth rising over the limb of the Moon on Christmas Eve, and later transmitted their famous reading of the first chapter of the Book of Genesis back to Earth, it was a genuine moment of hope for people in a fairly dire time. One famous letter to NASA thanked them for “saving” 1968. However, in the Apollo era it was clear what the mission was for—to show the world the superiority of the American system over that of the Soviet one, especially at a time when many nations were gaining independence from their colonial masters and picking sides in the Cold War. Things are very different now, so it is worth asking why NASA is attempting this at all. What is the purpose of Artemis?

The goal this time is a permanent base, rather than the brief exploratory visits of Apollo. In addition to its scientific utility, such a base could begin to exploit lunar resources to produce things like rocket propellant, solar panels, and metals. It makes sense to produce these things on the Moon because its gravity well is far easier to escape—it takes less energy to get something from the surface of the Moon to the orbit of the International Space Station than it does to reach that orbit from the surface of the Earth. The use of space resources in this way will radically amplify the amount of material we can use in space relative to how much we can launch on rockets, enabling humanity to live and work in space at large scale, and enjoy the near limitless energy and material resources of the solar system.