Books

Murder Most Foul

William J. Mann’s new book about the notorious Black Dahlia case is a valuable corrective to the cottage industry of speculative theories that proliferated after her murder in 1947.

A review of Black Dahlia: Murder, Monsters, and Madness in Midcentury Hollywood by William J. Mann, 464 pages, Simon & Schuster (January 2026)

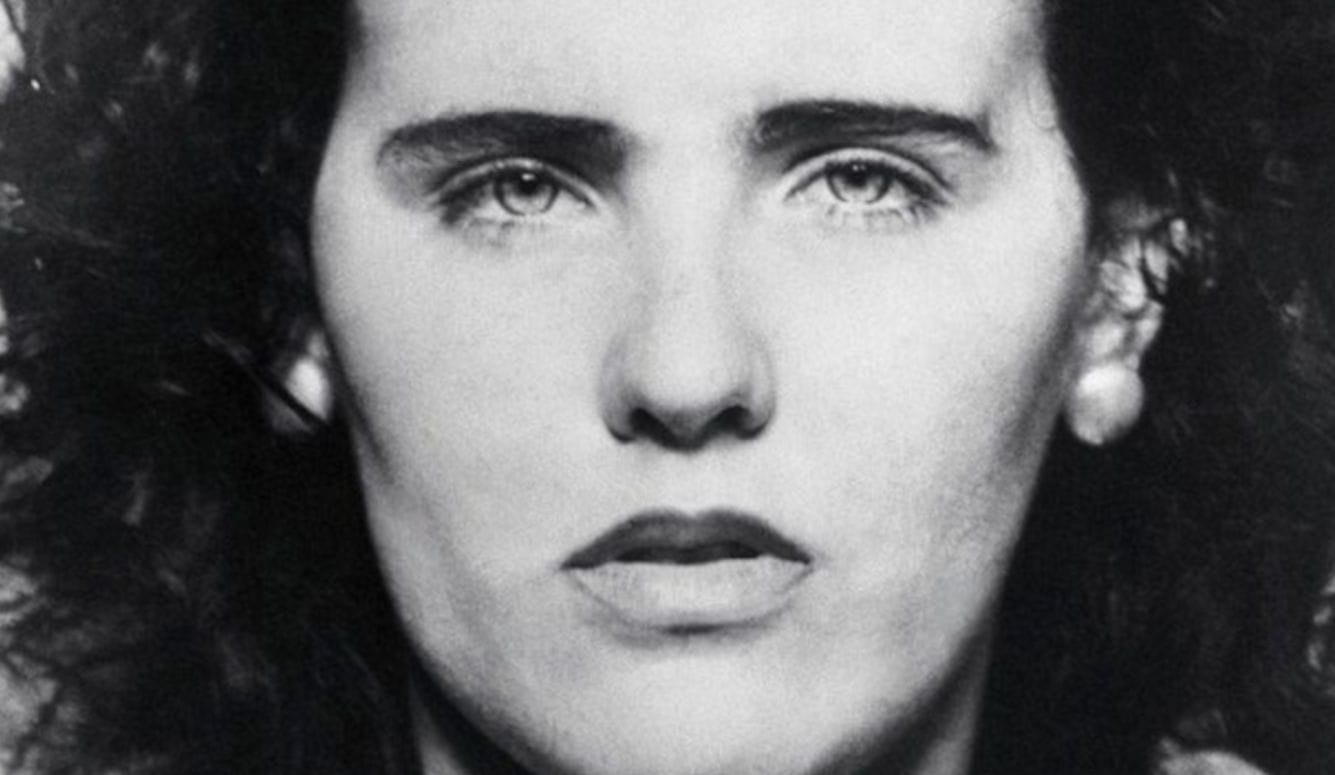

“The Black Dahlia” was the name given to 22-year-old Elizabeth “Betty” Short by the Long Beach Press-Telegram two days after her mutilated corpse was discovered in Leimert Park, Los Angeles, on 15 January 1947. A rumour circulated in the press that Short had habitually worn “black sheer clothing” even though none of her friends could recall seeing her dressed like this, and her oddly sinister nickname was subsequently lifted from The Blue Dahlia, a George Marshall film noir, written by Raymond Chandler and starring Alan Ladd and Veronica Lake, which had been released a year earlier.

As a result of this name, all that Elizabeth Short had been was discarded and she was reduced to an enigma at the centre of a notorious crime that remains unsolved to this day. As William J. Mann remarks in his excellent new account of the case:

Around those two words an entire industry would grow, with the dead woman becoming, as one chronicler called her, the “chanteuse in the Los Angeles Noir myth.” The Black Dahlia—a slinky, seductive creature that walks by night. Who was she? What secrets did she know? No longer was this just the tragic murder of a young woman. It suddenly became a glimpse into a sordid underworld rarely penetrated by the California sunlight but evidently very familiar to the victim. Within hours, the phrase “Black Dahlia” leapfrogged from Long Beach to Los Angeles, where it was used in final editions of the Daily News and Herald-Express that same afternoon. Within twenty-four hours, it would be the brand by which the story was known—and sold—forever after.

As Mann observes, this transformed Short “from innocent victim to femme fatale, prowling through the back streets of Los Angeles, followed by jealous boyfriends and sinister men, and, according to some, responsible for her tragic fate. ... Such a perception would influence the investigation going forward. Even some detectives would start to believe it.”

Mann’s book is a valuable corrective to the cottage industry of speculative theories that proliferated after her body was found in a vacant lot that January morning—an attempt to rediscover the real Elizabeth Short and to offer a portrait of a woman who was actually nothing like the noirish antiheroine that she became in the public imagination. She did not drink or smoke and she was not, we learn, even sexually promiscuous: “Being called ‘The Black Dahlia’ in the press sexualized a young woman, who despite her love of flirting, was in fact rather innocent when it came to sex.”

In fact, Short only displayed her “hungry eyes” to men in restaurants rather than her body, and more often than not, they took pity on her and bought her a meal. Contrary to the reputation she acquired in news reports and gossip columns as a prostitute or manipulative seductress, it seems that Short didn’t really like sex much. She would discourage would-be seducers with a picture of a dead aviator for whom she said she still carried a torch, or a picture of a soldier to whom she said she was engaged. As a last resort, she would claim to be a virgin. According to Mann, she was an innocent who had been abandoned and rejected by her father (briefly a suspect in her murder), and a lost soul in a city rife with corruption and misogyny. In retrospect, the amazing thing is not that she was murdered, it is that she survived in the Los Angeles dream factory for as long as she did.

Mann repeatedly widens the scope of his inquiry to place the Dahlia case in the context of what was happening in postwar America at the time. Although politicians had promised peace and prosperity, by 1947, the country was twitchy and fearful and angry. After a period of decline, the crime rate had begun to climb again, and between 1945–46 the homicide rate rose from 5 to 6.4 per 100,000. Anxious Americans worried about reds lurking under beds and UFOs hovering in the skies. “Take your pick,” Mann remarks: “Communists, Jews, homosexuals, blacks, aliens. They were all out to get you.” His noirish prose style sometimes evokes Raymond Chandler’s nightmare vision of California:

There was something out there. Something dark, something destructive. You could hear it in the police sirens wailing through the city. You could smell it coming through the walls of the Hawthorne Hotel. You could feel it in the overheated, overpacked rooms of the Chancellor Apartments. You could taste it in the foul breath of the men you were forced to kiss. ... It wasn’t something that only lurked in the dark alleys of America’s cities. It was everywhere. It was in the deep rural South and in quiet New England villages. And Elizabeth Short, like most everyone else, was caught in the middle of it.

By 1947, traditional gender roles and notions of family structure were threatened by women who strayed from the home. Young men returned from the war combat-ready and stressed out to find that the America they fought for had changed. Their anger and disaffection was contagious and it occasionally erupted in startling instances of horrific violence. In November 1944, a 34-year-old former Navy medic named Otto Stephen Wilson “slaughtered two women in hotel rooms, slicing one of them, Virginia Lee Griffin, from throat to vulva before yanking out her stomach and intestines with his hands.” Reactionary moralists blamed the rising crime rate on “female-headed households” which “grew by nearly 33 percent between 1940 and 1950.” And Mann cites a fanatical preacher who thundered: “We are faced simply and fundamentally by moral collapse.”