From the outset, Sydney could hardly have been less like a slave colony. The two most significant books the First Fleet brought with them were the Bible and Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England. Governor Phillip’s instinct for personal freedom and for convict reformation was in tension with his officer training and the British government’s intention to create a small and well-ordered penal settlement. Because convicts in New South Wales had more legal rights than prisoners in England and because they were permitted to do their own thing once they finished work for the day, soon enough many were materially better off than their family members back home. The soldiers’, ex-convicts’ and free settlers’ habits of self-advancement rapidly produced a lively and boisterous settlement quite at odds with the notion of a prison island and place of punishment. It’s fitting that the text chosen for Australia’s first Christian service was, “What can I render unto the Lord for all his blessings to me.” Harsh and strange though it could be, the new land was infused with faith and hope; and, in the first modern Australians, a spirit of can-do optimism.

As the first governor of the colony of New South Wales, Captain Arthur Phillip was the founder of modern Australia.

If not in command of a continental army, he was nonetheless commanding an unprecedented social experiment: a new settlement on the other side of the world, which turned out to be the world’s greatest ever exercise in criminal rehabilitation. He was tasked with leading a flotilla comprising six convict transports, two armed vessels and three cargo ships 17,500 nautical miles (32,420 km) to Botany Bay, on the east coast of the vast southern land that Captain Cook had named New South Wales eighteen years earlier.

Phillip well understood the magnitude of the venture. In the nine months prior to the fleet’s departure, in preparation for the journey and the founding of a new colony, he penned hundreds of letters to Navy Board officials. Biographer Alan Frost has noted “the touch of the visionary” in these writings: they reveal a leader determined to succeed. From food supplies, to legal administration, to harmonious relations with the native population, Phillip’s planning was wide-ranging and meticulous.

Once on board, Phillip treated crew and convicts alike with a fair-mindedness that struck some officers as indulgent. But that was the key to his success. A leader sets the standards.

Hardly a day after the Sirius weighed anchor on 13 May 1787, he invited an ailing midshipman, the fragile 23-year-old Daniel Southwell, to dine with him. “Rest up,” the commander told the young man, “take your time and eat well.” Southwell was grateful to receive such attention, for Phillip was a charismatic figure, diminutive in size but gifted with a powerful presence. Through a combination of kindness and resolve, and a tough love that gave no quarter to ill-discipline, he won the loyalty and respect of his men. “The Governor is certainly one of a thousand,” Southwell wrote to his mother.

Phillip was explicit that “[t]here can be no slavery in a free land and consequently no slaves.” A “free land” is an odd way to describe a prison settlement, but the new colony was unique from its very beginning. In America, the typical British convict had been taken ashore in chains and paraded through the streets in front of wealthy and often cruel buyers. Owners of convict labour in America had total control over their purchase. They could prohibit convicts from making money outside their primary duties, which they often did. They could confiscate the money that was made. If the convict’s legal status was greater than that of a slave, many who worked tirelessly in the plantations were made to feel little different. Not so in Sydney. Sydney Cove was not a walled gaol but an open settlement—the continual guarding of convicts was impossible—and convicts were accorded a degree of freedom unheard of anywhere else. They worked in their own clothes and without leg chains. They lived in huts—many built their dwellings themselves—and provided the labour that kept the colony alive. In what free time they had, they could trade or earn a wage and begin their second chance at life. They had legal rights and could own property. There was nothing like Sydney anywhere in the world.

The comparatively benign existence of convicts in Sydney was at odds with the prevailing view in London of a penitentiary where every aspect of the prisoner’s life was observed and controlled by watchful authorities. According to this perspective, convict ‘freedom’ risked descending into moral depravity. Although drunkenness was indeed a problem in New South Wales, and convicts could be lazy and dishonest, what these critics overlooked was the human capacity for self- improvement. Aspiration, it turned out, drove even convicts to ameliorate their own condition and to build social order.

Over time we have lost sight of how remarkable this was, but it was well understood, even if not widely accepted, back then. To a correspondent for the St James Chronicle, writing in January 1787, the despatch of the First Fleet was “more than the mere Banishment of our felons; it is an Undertaking of Humanity.” The Fleet looked much like a floating village, carrying almost 1500 people, including 775 convicts—582 men and 193 women—with two years’ worth of supplies.

Most of the officers on board were young, and some, like Watkin Tench, embarked in the “spirit of intellectual adventure” that marked the age. For others, the pain of separation from family was almost too much to bear. To the convicts below deck, suffering in the windowless gloom and hearing only the orders above that signalled departure, it must have felt as if they were leaving Earth altogether.

The Fleet sailed from Portsmouth to the Canary Islands, then to Rio de Janeiro before a final stop and resupply at Cape Town, reaching Botany Bay on 18 January 1788. A few days later, Phillip moved his ships some miles north to Port Jackson, a more suitable deepwater harbour which, crucially, contained a creek of fresh water running down into the cove he named after his ministerial chief, Lord Sydney. Here, on 26 January, Phillip raised the Union Jack and toasted King George III.

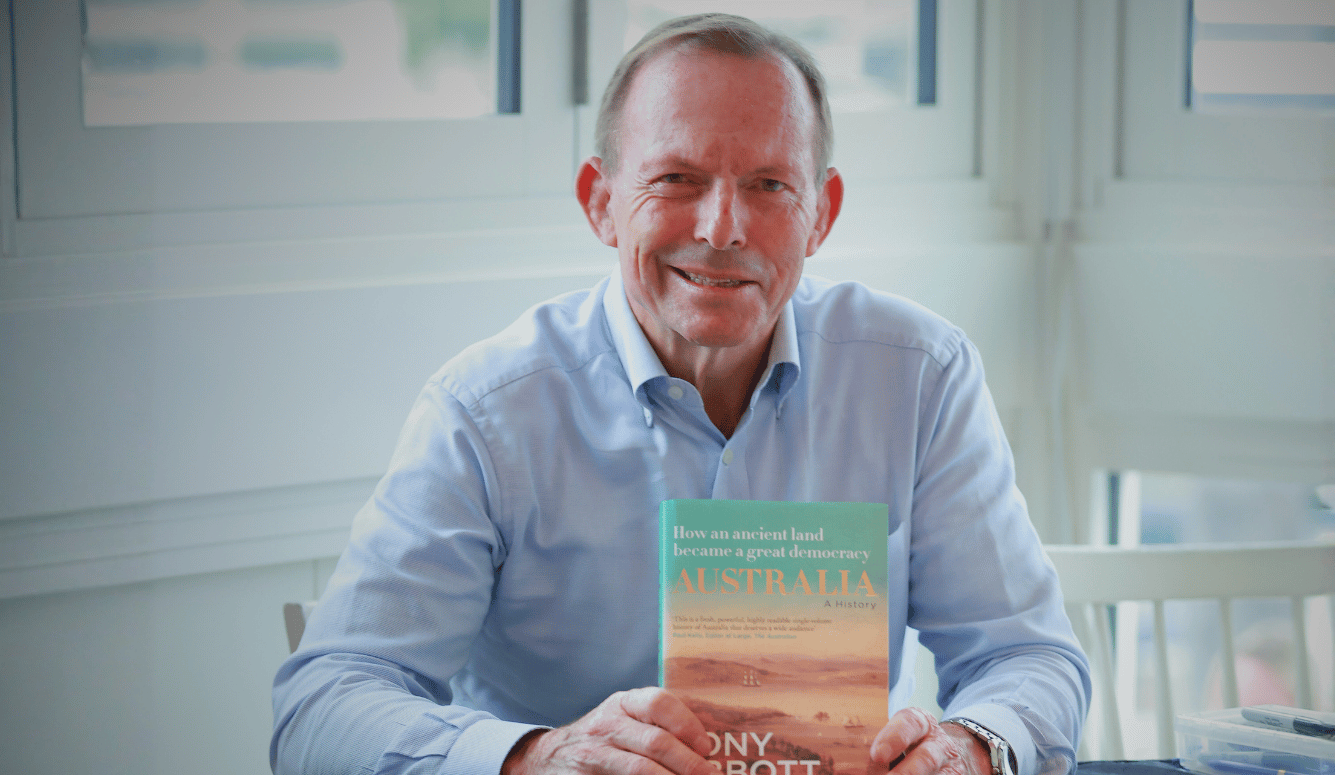

Excerpted from the book Australia: A History by Tony Abbott. Copyright © 2025 by Tony Abbott. Reprinted by permission of Harper Collins. All rights reserved.