Quillette Cetera

Inside Iran’s Deadly Protests with Shay Khatiri | Quillette Cetera Ep. 61

An Iranian-born political analyst breaks down the origins of Iran’s latest protest movement, the regime’s brutal response, and what a political transition could look like.

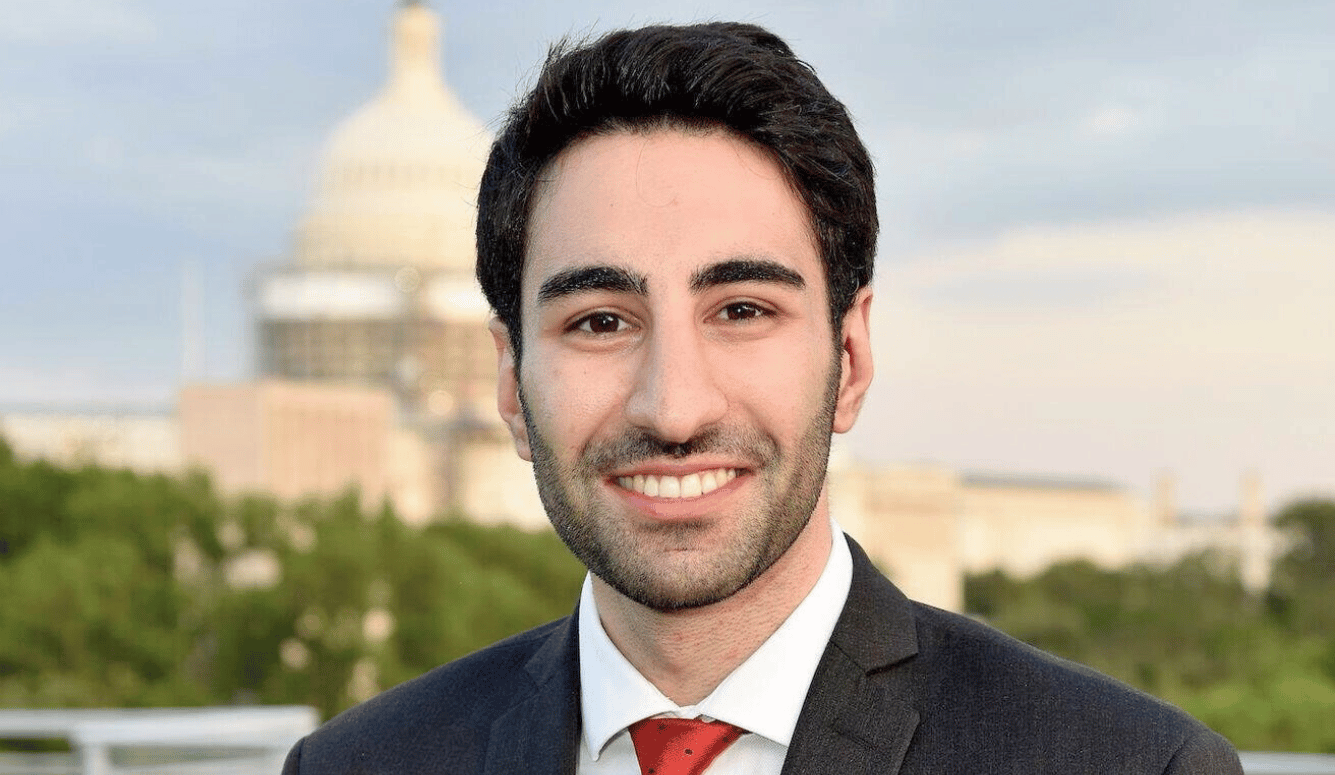

Shay Khatiri is a writer and policy analyst focused on Iran and its role in international affairs. Raised in the Islamic Republic before escaping to the U.S., he now serves as Vice President and Senior Fellow at the Yorktown Institute and writes The Russia–Iran File, a Substack dissecting the domestic and foreign policy strategies of both regimes. His work has appeared in The Wall Street Journal, National Review, The Bulwark, Providence, and Quillette.

In this episode, he joins Zoe to unpack the roots of Iran’s latest deadly protests, including the regime’s use of pellet guns and hospital raids to suppress dissent. He explains why so many Iranians are calling for foreign military intervention, what a post-regime Iran might look like, and why he believes a constitutional monarchy—led by Reza Pahlavi—offers the best hope for stability. They also discuss the role of the diaspora, the rise of underground Christianity, and why the West’s inaction may extinguish Iran’s last chance at revolution.

Editor's note: This transcript was generated automatically using voice-to-text software and edited for clarity and flow. While every effort has been made to preserve the speakers’ original intent and wording, there may be minor discrepancies.

Transcript

Zoe Booth: I want to do a brief overview or an update of what’s happening in Iran, considering it’s difficult to know exactly because of the digital blackout. But what can you tell our audience about this latest wave of protests?

Shay Khatiri: I like how you frame it as “the latest wave of protests” because there’s a tendency to separate protests in Iran: 2019 was said to be about gas prices—and I wrote one of my very first pieces for Quillette arguing that it was not about gas prices, that was just the trigger. 2022 was said to be about the hijab, and this time it’s about inflation.

My argument going back to 2009—which was the last time I was involved, in Tehran—is that was the last protest in Iran about a marginal issue. At the time it was demanding a recount for a fraudulent election. But even then, there was a transformation. People came out playing by the regime’s own rules—voting in restricted elections—and the regime didn’t even live up to those. After months of protesting, the chants changed from “Where is my vote?” and chanting the name of Mousavi, the candidate people supported against Ahmadinejad—those were the early chants—to chants against Khamenei himself: “Death to the dictator.” People didn’t start by saying that. That was a transformation.

That transformation was when people realised the regime was the problem, and the fraudulent election was not the cause but a symptom. In 2017, you had the first purely anti-regime protests. That time, it was much smaller than now but far more radical in its aims, and more violent than 2017. Then in 2019, again, you had the so-called gas price protests—larger than 2017, more violent. 2022, much larger, much more violent and...

ZB: So when you say “violent,” you mean the protesters are being met with more violence?

SK: No, I mean protesters engaging violently with security forces. In the past, they had engaged in peaceful protest and met violence in response. That norm had been broken by the regime, and the protesters were no longer shy about—not all of them, but many—initiating violence.

ZB: So we’re talking like property destruction, that type of stuff?

SK: Property destruction, even killing security guards, police officers. And in 2025—well, I guess December 2024 spilling into 2025—you have this new round of protests. And this is the largest and most violent, most radical round you’ve had.

And I want to emphasise the violent part, since you picked up on that. There is a fetishisation of peaceful protests in our societies, which is perfectly legitimate if you’re protesting in the United States—it’s the only legitimate means. The whole issue of civil disobedience begins with Gandhi in India and MLK in the United States. But it’s important to keep in mind—and I don’t want to diminish what Black Americans or Indians went through—but there was a degree of decency in the British and US governments that allowed peaceful protest to shame those governments into change.

That decency doesn’t exist in every government. It certainly doesn’t exist in the Islamic Republic. I always say, keep that in mind. Secondly, even for Americans who achieved their own independence, that was won through violent means. We call it the Revolutionary War, and it was a literal war.

So in certain contexts—certainly in the Iranian context—it is a legitimate means of political action. All civil means have failed for Iranians. All civil means have failed.

So this round was triggered by—and I want to emphasise, triggered by—the collapse of the currency. People started protesting in the bazaar. And leading chants... There were some demonstrations...

ZB: Why is it relevant that it started in the bazaar? Why is the bazaar such an important symbol? Is it in Tehran?

SK: We’re not sure how it first started, but it quickly spread. Many shopkeepers started, and I believe it was actually mobile phone shops to begin with. But it’s both important and not. It’s important because in the past, during the Constitutional Revolution of the 1900s, and again in 1979, the bazaar played a key role in driving change. Traditionally, the bazaar has been important because it’s where much of the commerce happens.

At the same time, it’s not that important because wherever the trigger might have been, it would have quickly spread regardless. As soon as the exiled son of the former Shah, Reza Pahlavi, issued a call for Thursday night and Friday night protests, the country exploded. Everybody was out. And throughout those two nights, we’ve had—by different estimates—about 12,000 to 20,000 deaths and 330,000 wounded.

ZB: Wow. So that shows that Reza Pahlavi does have a lot of support in Iran. He clearly has a lot of support in the diaspora too, because pretty much the only chants you hear—I was just at a rally on Saturday—and I think for Australians, looking at the Iranian diaspora, it’s hard to understand. It can look like a cult of personality. We’re like: “Why do you love this guy so much?” We don’t get it.

Because cults of personality—I mean, maybe you can talk about Trump—but in Australia, we don’t have any cult leaders or one specific figure we all go out and chant for. It’s very foreign to us. I gave a speech and I was actually asked to finish with “Javid Shah, Javid Shah.” And at first I was like, I don’t know if I feel comfortable saying it. For our listeners, it means “long live the King.”

But when I was there, I did my research. I saw how popular he is. I saw people in the crowd crying and holding up images of Pahlavi. And as I said in my speech, it’s my role to listen to Iranians. And if this is what Iranians want—and clearly the majority of you do want Pahlavi—then I will support you in that. That’s my opinion.

SK: You know, it’s funny, because I have these two brains. One is in Farsi and the other one is in English. It’s like my American brain and my Iranian brain. If you’re talking to me in the American context and you say anything about monarchy—you guys are a monarchy but we’re not—in the US, if you say anything about monarchy, it’s possible you’d end up in hospital. I would not put up with that.

But then you talk about Iran and I go immediately toward monarchy.