Politics

Stranded in History

China’s over-reaction to a measured remark about Taiwan made by the Japanese prime minister is an attempt to move the Overton Window.

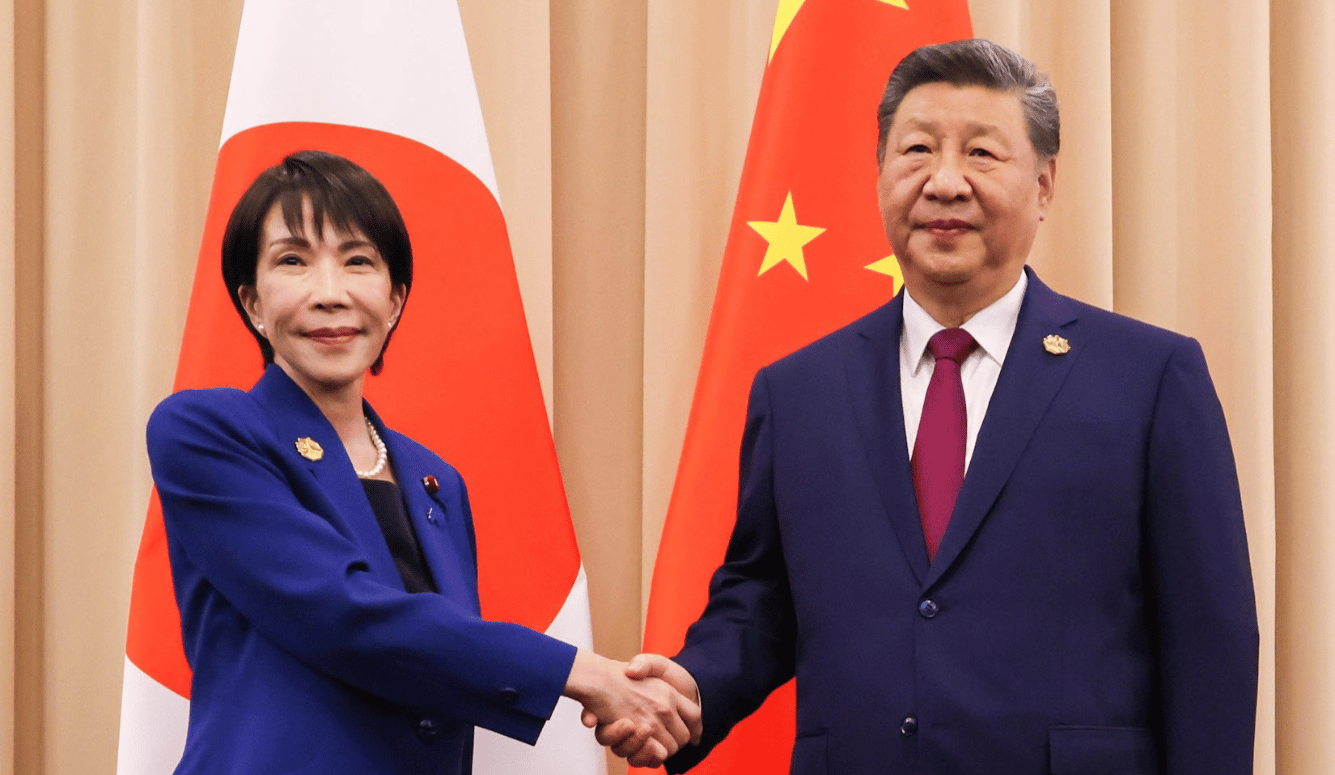

When Japanese prime minister Takaichi Sanae told a parliamentary session in Tokyo on 7 November that Chinese military force against Taiwan could constitute a “survival-threatening situation” for Japan, she knew that blowback would follow. Still, she may have been taken aback by the CCP’s first response, which was addressed to her personally. “If you go sticking that filthy neck where it doesn’t belong, it’s gonna get sliced right off,” said the Chinese consul general in Osaka. “You ready for that?”

These were crude words for a man whose very job title comes from a word associated with sensitivity and tact. But then, diplomats in communist China have never been the same breed as diplomats elsewhere. They are Leninists to the core. (The consul-general’s comment reminded me of Lenin’s infamous telegram: “Hang, absolutely hang, in full view of the people, no fewer than one hundred known kulaks, filthy rich men, bloodsuckers.”)

Marxism-Leninism was always a return to the barbarism of the ancient world; an explicit rejection of civilisation and all its bourgeois trappings, whether these were ideas about courteous speech or ideas about the sanctity of the human body. For communist leaders, the civilised world was a fraud masking exploitation. From Trotsky to Mao, they advocated tearing up roots, be they artistic, cultural, or moral. This was supposedly a destruction of all that was old in order to build something new. In practice, the communists built nothing, and only unearthed much older and darker things. As the Soviets swarmed into Yugoslavia in 1945, one of Tito’s Partisans remarked that it was “a return to the administrative methods of Attila and Genghis Khan.”

We treat Communist Party officials like reasonable counterparts, as if the donning of business suits has made them exactly like us. They are not like us. Takaichi’s interlocutor was positioned not just a thousand miles to her west, but also several centuries into the past: a distant and violent place in which the Chinese nation remains marooned. Those unfortunate enough to be arrested in modern China are sometimes beaten for days by police to obtain confessions, and those who are imprisoned are routinely tortured. Meanwhile, an emperor-in-all-but-name protects his position by purging and locking up potential rivals, as if that is simply the natural way to do politics.

Japan’s prime minister made her comments in the context of growing CCP aggression. She stated specifically that “if there are battleships and the use of force [over Taiwan], no matter how you think about it, it could constitute a survival-threatening situation” (the legal threshold for the mobilisation of self-defence capabilities). Tokyo’s longstanding position remains that Japan “fully understands and respects” the CCP’s claim over Taiwan, a position based on Article 3 of the Japan–China Joint Communiqué of 29 September 1972. But that is not an endorsement; it is the same carefully ambiguous language generally adopted by the democratic West, of which Japan is a part. The ambiguity is, of course, strategic. Beijing has never been quite sure how Tokyo would respond in the aforementioned worst-case scenario.

Takaichi’s suggestion echoes those made by Japanese politicians in the recent past. In 2021, former prime minister Abe Shinzo said that “a Taiwan contingency is a Japanese contingency.” The same year, Japan’s minister of defence Nobuo Kishi pointed out that the stability of Taiwan is directly connected to that of Japan. “If a major problem took place in Taiwan,” deputy prime minister Taro Aso said that July, “it would not be too much to say that it could relate to a survival-threatening situation [for Japan].” This is the first time, however, that the sentiment has been expressed by a sitting prime minister in public and in reference to a specific scenario. This suggests that we may be dealing with a new and tougher Tokyo.

Takaichi’s comments were eminently sensible. There is no possibility of remaining neutral in the event of a “Taiwan contingency.” Japan’s islands bristle with US military bases, the activation of which must obviously involve Washington–Tokyo dialogue. And it’s not as if staying out of “China’s affairs” would be a safe course of action. Some 32 percent of Japan’s imports and 25 percent of its exports move through the Taiwan Strait each year. That’s US$444 billion worth of trade that stands to be disrupted by an invasion or blockade.