UK Politics

The Alliance Labour Needs?

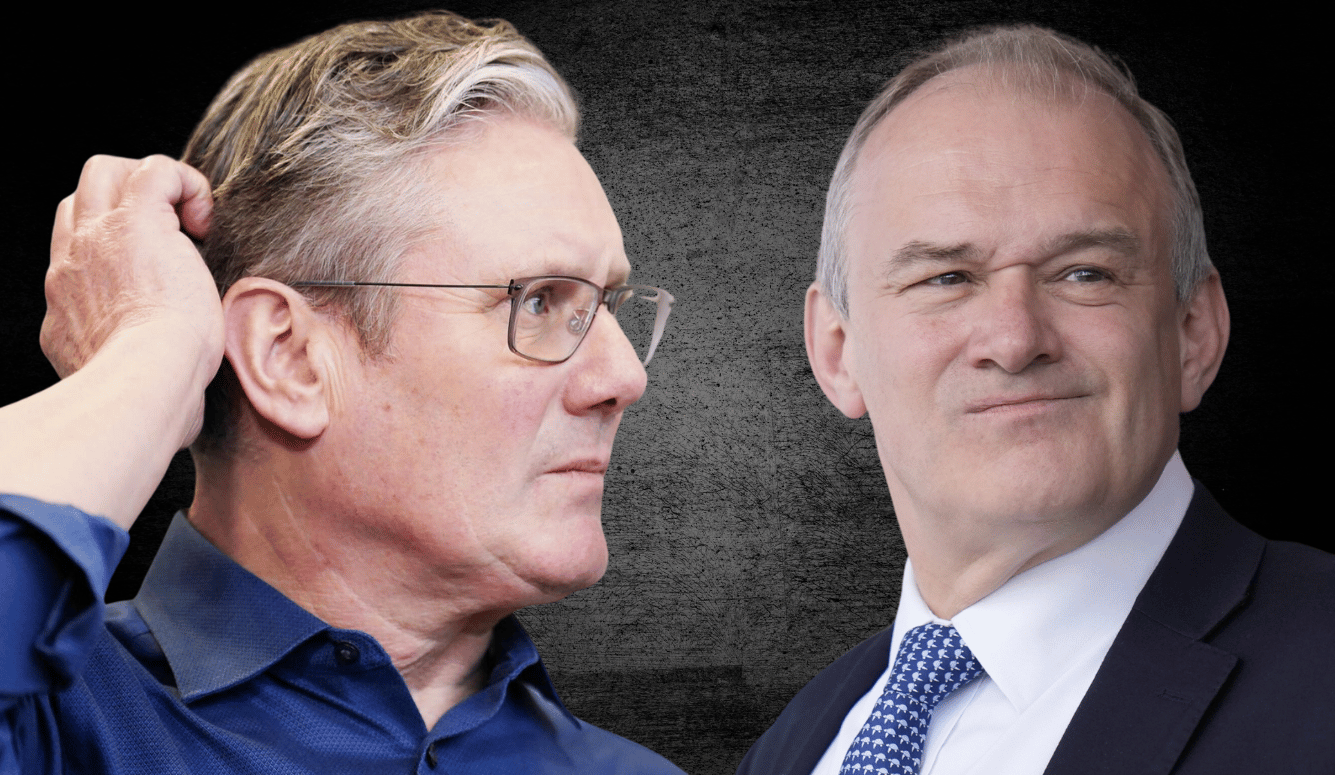

Could a Labour-Liberal Democrat pact save Starmer’s collapsing government?

The UK’s Labour government is in a parlous state. Following a collapse in popularity that was unprecedented in both speed and extent, Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s days in office seem to be numbered. For this to befall a government after less than sixteen months in power is astounding. The Labour Party will be faced with a debate about its future within the next year.

Strategy, policies, and ideas will—or should—dominate the upcoming debate. Two competing schools of thought have already formed. One has been dubbed “the McSweeney strategy” after the Prime Minister’s chief of staff, Morgan McSweeney, though it is unclear to what extent he himself endorses it. On this view, the Labour Party must make more efforts to appeal to voters for Nigel Farage’s immigration-sceptical hard-right party Reform, while retaining the Reform-curious Labour voters and the hero voters the party won back last year—Brexiteers who voted Tory in 2019 in protest at Labour’s commitment to remaining in the EU and at Jeremy Corbyn’s highly unpopular leadership. The Labour Party must be the party of the working class—a coalition that includes those working-class Brits who are currently plumping for Reform.

There is a problem with this view, however. The majority of those who have defected from the Labour Party recently have found refuge in the Liberal Democrats, Plaid Cymru (the Welsh nationalist party), and the Greens. Those who have gone over to Reform—and the tiny group who have switched their allegiances to the Tories—are in the minority. Moreover, attempting to erode the popularity of Reform appears unachievable. Most Reform voters hold the Labour Party in contempt and are considerably more likely to support the Conservatives—although Andy Burnham, who has been Labour’s Mayor of Greater Manchester since 2017, is popular with a third of 2024 Reform voters. Burnham, who has been dubbed “The King of the North,” is an outlier, however. For Labour in general to regain the trust of most Reform voters would require the kinds of policies collectively known as “hippie-punching,” which would only alienate the majority of Labour defectors, including those in marginal seats. It would also alienate most Labour Party members—who overwhelmingly believe that the government should move further to the left. In any future leadership contest, the McSweeney strategy, then, is likely to be blamed for the party’s current predicament.

Some suggest that the Labour Party should court the support of working-class voters through talk of the “national economy” and promises of reindustrialisation. But this is just another delusion. Those working-class people who back Reform—many of whom have not voted for the Labour Party in years—do so because of their cultural conservatism, not because they believe in economic interventionism. Bidenomics did not save America from Trump, nor will a similar strategy win back the Red Wall for Labour.

It is precisely because the Labour Party failed to convince a sufficient number of authoritarian leftist voters that it ended up with only 34 percent of the vote, a third of whom prefer Corbyn to Starmer. Attempting to convince these voters with a Reform-friendly strategy is a gambit that would make the party look more absurd than William Hague at the Notting Hill Carnival. It would be a hiding to nothing. The strategy most associated with Blue Labour (right-leaning Labour) lost because Blue Labour’s analysis is completely right: the Labour Party is the party of the Progressive Mum not the Common Good Dad.

Yet there is another strategy on offer. This was described to me by a former Labour minister as the McTernan strategy (named after Tony Blair’s former aide John McTernan, who has moved to the soft Left). Under this strategy, dubbed A New Popular Front, the Labour Party would be at the head of an alliance that would include the Green Party and Corbyn’s vehicle, Your Party. The aforementioned Andy Burnham has made positive noises about working with the Liberal Democrats, the Greens and Jeremy Corbyn in his recent intervention on the direction of the Labour Party. For some around the soft-left pressure group Mainstream, such as Neal Lawson, an alliance of the forces of the Left could put an end to what they perceive to be a new Great Moving Right Show.

Yet a move further leftwards could be a disaster. It would alienate Reform-curious Labour voters and 2024 Conservative-to-Labour voters. It would also provoke anti-Labour tactical voting and potentially give ammunition to both parties of the Right. Moreover, there is no guarantee that such a strategy could regain Labour voters who have been moving to the Left. Why vote for a pale imitation of Zack Polanski (the leader of the Greens, who describes himself as an “eco-populist”) when you can have the real thing? A formal alliance with the Greens and with Corbyn’s new outfit may resolve this tension but it would further alienate those on the right of Labour’s voter coalition.

Neither prospect provides much comfort for Labour. And even if they retain their existing support, it might not be enough to win the next general election. The coalition that won in 2024 could find itself swamped by anti-Labour tactical votes.

Yet if the Labour Party is stuck between Polanski and Corbyn on its left, and Farage well to its right, could it make sense to make common cause with the Liberal Democrats? Rather than fighting each other at the next election, could both parties agree on an electoral pact or a coupon election—i.e. rather than competing, might they agree not to contest each other in certain seats? This option has been considered by some Labour and Liberal Democrat MPs as a possibility. One former Downing Street adviser is privately supportive of the idea. Could it happen?

The Historical Precedent

Such talk is heresy in Labour circles, yet Labour and Liberal cooperation has a long history. The struggles for the extension of the franchise and for the rights of unions to organise were waged under the banner of Gladstonian liberalism. As Ben Jackson noted in 2011: “there have been lines of continuity from the Paineite radicalism of the late eighteenth century to Chartism to popular liberalism to the ethical socialism of the early labour movement.” It was the Liberal Party that first legalised trade unions in 1871 and the liberal John Stuart Mill was among the first to propose the existence of a party representing the labour interest in Parliament.

The trade unions initially supported the Liberal Party and the first Lib-Lab MPs, Thomas Burt and Alexander MacDonald, were elected in 1874. In 1880, they were joined by the Trade Union Congress (TUC)’s parliamentary committee secretary, Henry Broadhurst. William Gladstone himself expressed a desire to see more Lib-Lab MPs elected, in his famous Newcastle speech of 1891, but Liberal committees failed to select more working-class candidates. Keir Hardie, Arthur Henderson (a Liberal Party agent), and Ramsay MacDonald all tried to get selected as Liberal candidates. When Keir Hardie stood in Mid Lanarkshire by-election as an Independent, he said: “I am in agreement with the present programme of the Liberal Party so far as it goes.”

The Labour Representation Committee was formed to provide a distinct voice for Labour, independent of the Liberals, but it retained a strong liberal influence. Four out of the five members of the LRC’s preparatory committee were Lib-Lab types. When Keir Hardie and Richard Bell were elected as the first LRC MPs, they worked with the Liberals in parliament (despite some hostility from Lib-Lab MPs). In 1903, the LRC negotiated the Gladstone-Macdonald pact with the Liberal Party, whereby the Liberals gave the LRC a free run in 31 out of the 50 seats they contested in the upcoming general election (which helped the growth of the nascent Labour Party in 1906). Further agreements and deals between both parties were formed in order to keep the Unionists out. In a reading list of members of the first Parliamentary Labour Party, John Stuart Mill featured heavily but not Karl Marx.

The unions shifted their allegiances from Liberal to Labour following the Taff Vale judgement. In 1901, the Taff Vale Railway Company successfully sued the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants (a trade union) for damages caused during a strike. An appeal to the House of Lords was unsuccessful—the Lords ruled that trade unions could be sued for losses caused by industrial action. This made it clear to union officials that they needed a parliamentary party that specifically championed their interests. (In 1906, the Liberal government of Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman passed the Trade Disputes Act, which established the unions’ legal immunity.)

Nonetheless, there was still cooperation between the Liberal Party and the new Labour Party. Labour MPs supported the Liberal government of 1910 and backed many of its reforms. There was substantial agreement on free trade, Home Rule, progressive taxation, pensions, and internationalism. The Liberals had also made it a requirement for trade unionists to opt out from giving political subs to their unions (which would go to support the Labour Party). Before 1914, Labour did deals with the Liberal Party, with most Labour MPs owing their seats to Liberal support. Some speculated that the Labour Party’s creation was a mistake, with some believing that there would be a permanent alliance between both parties. When Lloyd George invited Ramsay MacDonald to join the Government (who ironically grew to dislike the Liberals more than the Conservatives), it was thought by some that he could end up succeeding Asquith as the leader of a joint formation of Liberal and Labour Parties.

The main breakthrough for the Labour Party was when the Liberals split following Lloyd George’s coup against Herbert Henry Asquith, which positioned it as the main Opposition to the Coalition which had won the previous election. When the Liberals split following Lloyd George’s coup against Herbert Henry Asquith, the Liberals under Asquith backed the first Labour government, allowing them to take power despite a hung parliament in 1924, and in 1929 (now under Lloyd George, who had succeeded Asquith in 1926), repeated this by supporting the second Labour government, following another hung parliament.

Further Liberal–Labour cooperation occurred in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In 1896, Ramsay MacDonald joined the Rainbow Circle, a progressive discussion group that included liberal thinkers J.A. Hobson and Leonard Hobhouse. In a column for the Manchester Guardian, Hobhouse praised the young Labour minister Clement Attlee’s definition of socialism as the belief that “freedom and development of individual personality can be secured only by harmonious cooperation with others in society based on equality and fraternity.” He saw no salient difference between the ethical socialism espoused by Attlee and the social liberalism that he propounded. Chancellor of the Exchequer Phillip Snowden’s first Labour budget did not draw upon Marx or Engels, but on Gladstone. Indeed, the demands for Scottish Home Rule have their roots in the Liberal case for Irish Home Rule. The postwar Attlee Government itself drew upon the work of William Beveridge and the economic philosophy of John Maynard Keynes—both liberals. The Labour Party also acknowledged that it shared much in common with the Liberals. A private document for party activists in the 1945 election stated: “Liberal policies draw heavily on Labour’s economic policies. Liberals are asking the electorate to believe that unlike Labour’s policy, they are quite different from socialism. There is no radical difference between the programmes”. The editor of The Guardian, AP Wadsworth, had been keen to see a Labour government elected with Liberal support. Megan Lloyd George, the daughter of David and a Liberal MP, had been in talks with Deputy Prime Minister Herbert Morrison in order to encourage cooperation between both parties. Lloyd George would later defect to the Labour Party out of frustration with what he perceived to be a rightwards drift in the Liberal Party.