Art and Culture

Cynicism and Cigarettes

Richard Linklater’s film about the making of Jean-Luc Godard’s ‘À Bout de Souffle’ is a delight.

Nouvelle Vague—Richard Linklater’s new movie about the making of Jean-Luc Godard’s landmark debut feature À Bout de Souffle (Breathless)—is a sheer delight. I’ve seen Breathless four times over the years, and I devoted much of 2024 to writing a mammoth two-part retrospective of Godard’s relentless career and artistic suicide over the 62 years that elapsed between his 1960 breakthrough and his death (by actual suicide of the assisted kind) in 2022 at the age of 91.

So for me, Nouvelle Vague was a reunion with familiar names and faces from Godard’s early life: his fellow writers at the highbrow Parisian film journal Cahiers du Cinéma (still in existence) where he got his first break as a critic. Several of those writers, including Godard himself, became the leading lights of the late 1950s/early 1960s new wave movement in French movie-making, from which Linklater’s film takes its name. The aim of this movement was to make an intellectual kind of cinema that also resembled life in its raw immediacy. To that end, its progenitors employed a mix of loose vérité cinematic techniques, postmodern self-referentiality, improvised dialogue, intimate stories, and real locations instead of purpose-built sets (usually in the interests of saving money). Godard carried all of this to near-parodic extremes, and Breathless was to remain his signature movie for all of his very long life.

In making Nouvelle Vague, Linklater selected actors for their startling resemblance to Godard and his confrères as they slapdashed Breathless together—or sceptically witnessed it being slapdashed together—during August and September of 1959. There on the screen is Godard’s best friend and rival, François Truffaut (Adrien Rouyard). And there’s Jacques Rivette (Jonas Marmy). And there’s Godard himself, brought to life in a debut performance by 31-year-old Guillaume Marbeck, whose physical resemblance to his character—the needle nose, the omnipresent shades, the lupine profile, the prematurely receding hairline and widow’s peak—makes him the most uncanny of all of Linklater’s casting choices.

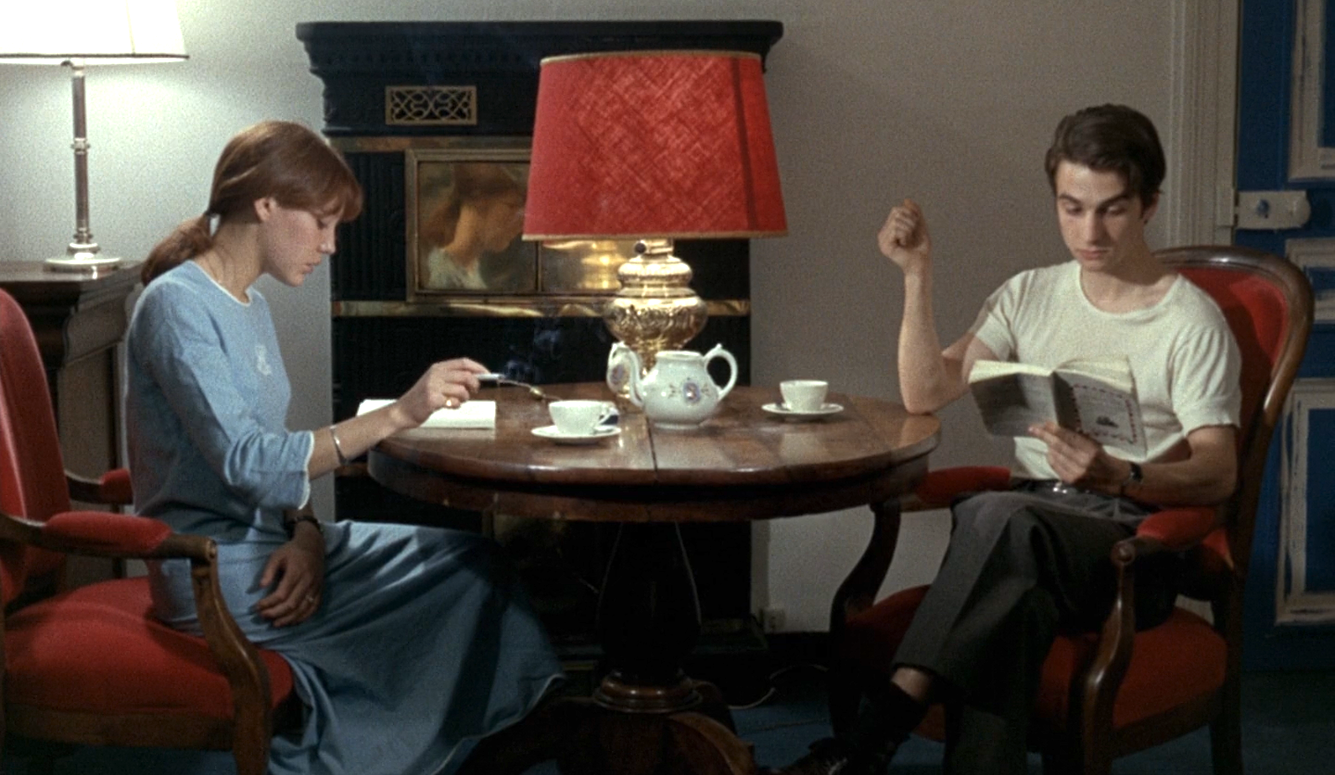

To assist his film’s evocation of the world of sixty years ago, Linklater filmed Nouvelle Vague on grainy monochrome film stock in the 1.37:1 academy aspect ratio that prevailed before the standardisation of the widescreen and cinemascope formats. Nearly all the dialogue is in French with English subtitles (Linklater had the English screenplay translated into French, and he managed to wrangle a crew of mostly French actors despite not being a French speaker himself). As a result, watching Nouvelle Vague in 2025 feels a little like watching an actual Godard film in an American arthouse cinema during the Kennedy administration.

You don’t have to know anything about Breathless—or Cahiers or the French new wave or Godard himself—to be beguiled by Linklater’s film. I watched Nouvelle Vague with a friend who had never seen Breathless and had no idea what was going on for most of the film. Nonetheless, she was enchanted by the late-1950s evening gowns and bouffant skirts worn by Zoey Deutch (who plays Breathless’s twenty-year-old female lead, Jean Seberg), the jazz score, the detailed recreation of mid-century Paris, and the sheer energy and fun of Godard’s seat-of-the-pants directorial style.

Oh, and the cigarettes. The first half of the 20th century was the golden age of smoking. Godard was a lifelong chain-smoker, as was Jean-Paul Belmondo, whom Godard cast as Breathless’s male lead (Aubry Dullin in Linklater’s movie), and so was the small-time hood Belmondo played in Breathless. Seberg also smoked like a chimney both on and off the screen, and in Linklater’s movie she sips wine during an elegant luncheon with a goblet and cigarette in the same hand without setting fire to the tablecloth. Smokes might cause lung cancer in real life, but I found watching mid-century sophisticates elegantly manoeuvring them on film endlessly entertaining.

Nouvelle Vague’s high spirits and heart-on-sleeve affection for its period setting make it a far better movie than Linklater’s simultaneously released Blue Moon, another period piece (set in March 1943) that also purports to dissect show business. Unlike the upbeat Nouvelle Vague, Blue Moon is a real downer: a lugubrious 100-minute near-monologue delivered in real time by the legendary Broadway lyricist Lorenz Hart (“Blue Moon,” “The Lady Is a Tramp”) after he is dumped by his longtime tunesmith collaborator Richard Rodgers in favour of Oscar Hammerstein. For more than an hour and a half, Hart whinges, kvetches, cracks off-colour jokes, derides Oklahoma! as“cornpone,” and half-heartedly courts an arty blonde gold-digger who has come to the bar in the hope of furthering her career as a stage designer. It’s hard to believe that the same Linklater who produced this depressing and mean-spirited portrait also managed to craft the lighthearted valentine to Breathless.

It sounds like heresy to say so, but Nouvelle Vague is also a far better movie than Breathless, which lurched into iconic status due to its perfect timing and Godard’s preternatural feeling for what educated postwar audiences craved in terms of subject matter and style. There was no screenplay. Truffaut was nominally the screenwriter, but he never got past a thirty-page treatment that fictionalised a story that blazed through the French tabloids in 1952: a low-level gangster stole a car, killed a pursuing motorcycle cop, and then went on the lam with his American journalist-girlfriend. Godard altered the criminal’s name from Michel Portail to Michel Poiccard and talked Belmondo, who was then a near-unknown, into taking the part. Godard changed the American girl’s name to Patricia and had her hawking copies of the New York Herald Tribune along the Champs-Élysées while she sought her own break as a reporter.

Godard also changed Truffaut’s ending, which had Poiccard running hopelessly from his implied but never-shown fate. In Godard’s film, the police catch up with Poiccard and shoot him in the back after Patricia betrays him and divulges his whereabouts. As for dialogue, Godard sometimes wrote it piecemeal in a school notebook while he sat in a cafe before shooting began. More often, he simply had the actors improvise. And if they drew a blank or didn’t get their lines memorised by shooting time, it didn’t matter. Godard shot Breathless handheld using a bulky Caméflex Éclair camera usually used for newsreels, and it was so noisy that all of the dialogue had to be re-dubbed in a studio. He wanted an amateurish look and also the sense of urgency he thought could be achieved with newsreel-stock film, fly-by-night production methods, and forcing his actors to invent many of their lines.